By Shamoyita DasGupta

Meregildo Carrillo harbors no regrets.

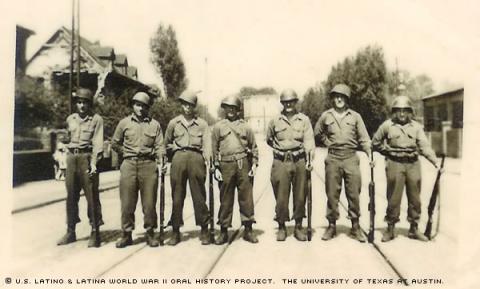

A decorated soldier, Carrillo served in World War II in France in the 79th Infantry Division, both despite and because of his own personal battles.

Born in San Angelo, Texas, on April 13, 1924, Carrillo’s mother left him in the care of his grandparents when she remarried. For several years, he said he was shuttled back and forth between families in different Texas cities.

Throughout his childhood, and even for several years after the war, Carrillo lived on meager finances.

“We had to do without a lot of things – essential things, like food and clothing and shoes,” Carrillo said. “But we made it through.”

Carrillo’s education was also limited. He briefly enrolled in school at the age of six, after one of his father’s employers insisted that Carrillo attend. However, his enrollment caused an immediate uproar in the community, with families refusing to allow their children to ride on the same bus as him. Ultimately, Carrillo withdrew, concluding the only two days of formal education he would experience as a youngster.

Carrillo worked odd jobs, often accompanying his stepfather, but never held onto these jobs for long.

When he registered for the draft at age 18, he had limited knowledge of the war in which America was embroiled. But he soon found himself reporting to the local Draft Board in San Angelo, making arrangements to go to Lubbock to take an entrance examination. Although Carrillo said his employer tried to discourage him from reporting, Carrillo said he was determined to participate in the conflict.

“Really, I didn’t know any better,” he said. “Everyone was going, and I wanted to go too.”

Unfortunately, military life didn’t turn out to be an escape from the discrimination he’d become so familiar with in civilian life. One day in Lubbock, during the induction process, Carrillo and some other prospective soldiers were told to wait until 2 p.m. So Carrillo went to a restaurant to eat lunch, as part of a group of approximately 30 men of either Caucasian or Mexican-American descent. Upon their arrival, he recalled the restaurant’s owner refusing them service. (As if that weren’t bad enough, Carrillo said he experienced similar discrimination when yet another eatery refused the group service the next morning.)

Carrillo’s problems didn’t end there. Upon taking an entrance exam for the Army, he said he was informed he could not enter because he could not read or write.

“Just because I don’t know now, doesn’t mean I can’t learn,” Carrillo recalled telling the screener.

Ultimately, Army officials relented and allowed him into a six-week program to teach him reading and writing skills, Carrillo said. And, after passing the exam, Carrillo went to Camp Wheeler in Georgia to begin basic training. He was officially inducted into the Army on Sept. 22, 1943.

Despite his new status as a soldier, Carrillo recalled continuing to face prejudice. Before leaving for the war, he returned to San Angelo for four days. During the trip, he said non-Latino Caucasians pulled him and several other Mexican Americans from rail cars, leaving them to wait for later trains.

Carrillo returned to Georgia for yet more training. The Army said more soldiers were needed in Europe, so he was sent from Camp Wheeler to a different camp before shipping out in the summer of 1944 to Churchill, England, for still more training.

Among other battles, he participated in the Normandy invasion on D-Day. The military next gave Carrillo an assignment in La Haye-du-Puits, France, where he recalled being so close to bomb explosions that he began to lose his hearing.

Carrillo also fought in Le Mans, Lunéville, Embermenil, and Haguenau, as well as other parts of the Alsace-Lorraine region on the then-disputed French-German border.

But expressions of prejudice persisted against him, even into the theater of battle. For example, he recalled two new soldiers ranked below him joining his unit and frequently referring to him as “the Mex.” He remembered being called that name again when, after he was promoted to the rank of staff sergeant, a tank commander disregarded Carrillo’s status and, instead, asked him repeatedly if he was “a Mex.”

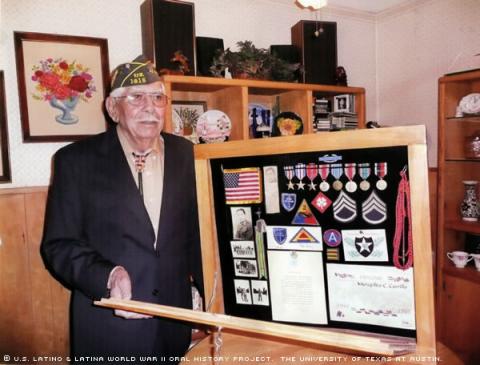

Carrillo still persevered as a soldier and earned several honors, including two Silver Stars, one Bronze Star, one Good Conduct Medal, one American Theater Ribbon, one Victory Medal, a European Theater Medal, an Army of Occupation Medal, a French Croix de Guerre and a Combat Infantry Badge, in addition to a thank you note from President Harry S. Truman.

Staff Sgt. Carrillo was in Czechoslovakia when he learned of his discharge on Nov. 22, 1945. He said he had generally enjoyed his time in the Army, so he immediately reenlisted, ultimately getting discharged as a platoon sergeant on May 21, 1947, in Fort Sill, Okla.

Shortly after his second discharge, Carrillo married Josephine Juarez, whom he had known since childhood. Although Carrillo and his family struggled to earn a living, he said he has led a good life.

“I feel that life has been good to me now that I am where I am,” Carrillo said. “I think that I have achieved whatever I was supposed to achieve. I’m at the top. No regrets.”

Mr. Carrillo was interviewed in Albany, Calif., on July 15, 2009, by Lawrence J. Polon.