By Carrie Nelson

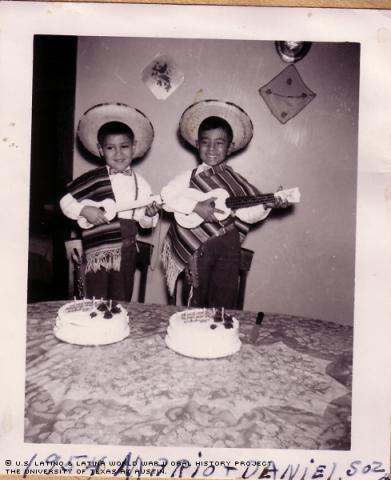

Manuela Ontiveros dedicated her life to her family and community and to preserving her treasured Mexican heritage and traditions.

"You instill in your children and grandchildren pride [in their heritage]," Ontiveros said. "Even though my grandchildren are half white, they know how to cook enchiladas and tamales.

"I try to pass on the traditions of the Mexican people, traditions that they have nothing to be ashamed of," she said.

"I'm 81 years old, so I've seen a lot," Ontiveros said. "I'm glad I grew up in this community."

Ontiveros was born Manuela Garcia on Dec. 22, 1921, in Lockhart, Texas. Her family moved to Saginaw, Mich., where she currently resides, when her father, Frank Garcia, took a job there. She attended Potter Elementary and graduated from St. Joseph's High School in 1941.

"My dad would tell my grandmother, 'I don't know why she's going to school, she's just going to get married,' but my grandmother still made me go so that I would have an education," Ontiveros said.

Ontiveros is the only surviving member of the Garcia family, which included five sisters and two brothers.

"I'm the oldest living member of my family, so it gets lonely, but I'm satisfied with my life," she said.

Her sister and mother, Theresa Cortez Garcia, died of spinal meningitis when Ontiveros was 9, leaving her grandmother to raise the remaining children while Frank worked.

Ontiveros married Jesus Quiroz Ontiveros in 1941 after she graduated from high school. Jesus, 20 years her senior, worked as a laborer for Chevrolet and the Grey Iron Foundry for 37 years. He and Ontiveros were married for 36 years before he died of lung cancer in 1977.

"He was a very community-conscious man," she said. "He was the president of the [Union] Civica [Mexicana] and wanted our kids to go to school because he only went to school through the third grade."

They had five children, four of whom are still living. Raquel, also known as Rachel, drowned while visiting Cabo San Lucas in Baja California, Mexico, in 1998.

"It[‘s] still hard for me to talk about her because it hurts," Ontiveros said. "She died young. She got her doctorate while working and being a single mom; I was so proud when she got that."

In addition to being a housewife, Ontiveros has worked throughout her life in her community by serving on boards, volunteering and helping preserve Mexican heritage. For example, she participated in the Young Women's Christian Association (YWCA) as a young women when her aunt, Adelia, took her to meetings.

"They were all professionals, and it made me feel kind of funny being on the board because I was just a housewife," Ontiveros said. "But I learned a lot from them."

Along with Jesus, Ontiveros was also a member of the Mexican Civic Union, to help fight discrimination.

"Men were coming back from the war [World War II], and even though they served [the U.S.], they were discriminated against," she said.

At the time of her interview, she was participating in the Bridge of Racial Harmony.

"We have different people come and talk about their experiences [with racism]," Ontiveros said.

She also spent nine years mentoring children who were behind in reading.

She says it was rewarding to observe children she helped progress and succeed.

"It's amazing what you can do," Ontiveros said. "You can influence a lot of people, and I'm glad."

She also enjoys being active in politics. For example, as a member of the League of Women Voters, she helped start the Saginaw chapter of the League of United Latin American Citizens (LULAC). She also served as an election inspector and helped register voters.

Mexicans need to be knowledgeable on where to get help, whether it be a lawyer in regards to civil rights violations or an elected official for making their needs known, Ontiveros says.

"I recently attended a fundraiser for a candidate, and it helps to have a representative or senator you know to get things done," she said.

Ontiveros went back to school in 1975, at age 54. After getting her teacher's certificate, she taught kindergarten, first, second and fourth through eighth grades for 11 years until retiring in 1986. She started as a teacher's aide, attending through a grant Delta University and Saginaw Valley State University, where she earned her teaching certificate.

"When you first go back to school, you're scared," Ontiveros said. "I never thought I'd finish, but I did."

Ontiveros learned Spanish from her grandmother, Catarina Sanchez. She’d sound out letters, read the Mexican newspaper and talk to her grandmother in Spanish to help her learn the language.

"My grandmother would say, 'You're going to school, aren't you? So you should learn Spanish,'" Ontiveros said.

"My grandmother was a member of a church ladies organization, and she took me along with her to help me learn Spanish," Ontiveros said, adding that Catarina spoke only Spanish, which she interpreted for her.

Ragardless, Ontiveros says she still had to take Spanish classes to become a bilingual teacher.

The Mexican Civic Union members would go to public schools and do original Mexican cultural dances. Their goal was to build a meeting hall for the Mexicans in Saginaw like the other groups had.

"We had our dances in any hall we could get," Ontiveros said. "The Italian [people] and Polish [people] had their halls, so the Mexicans decided to build a hall."

And the Mexican community of Saginaw did just that.

"We wanted to have a hall because we wanted to keep young men in line," she said. "We wanted to show them to be proud of their heritage."

Ontiveros’ grandmother also taught her the Mexican culture through cooking and speaking Spanish.

During the Depression, Catarina boarded Mexican men so they could eat good Mexican food and be around their people. She also made corn tortillas and Mexican cheeses, which Ontiveros and her sister would sell to Mexican families.

"My grandmother was very protective of me," Ontiveros said. "I wasn't allowed to go out alone or to the dances. It's just part of the Mexican culture."

In short: "Nothing from Mexico was ever bad, it was all good," Ontiveros said. “[Catarina] instilled in me a lot of love for a country I had never been to."

Mrs. Ontiveros was interviewed in Saginaw, Michigan, on October 19, 2002, by Raul Garcia, Jr.