By Julia Bulhon

“War is horrible, but it helps you grow,” said Navy veteran Luis Diaz de León, of witnessing conflict’s brutality first hand.

As if that weren’t enough, Diaz de León has also withstood racism, earned a master’s degree, raised a family and campaigned for a United States Senate seat within his lifetime.

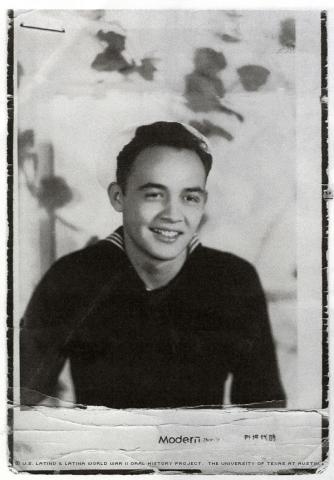

Still a teenager, he entered the Navy on March 2, 1944. His rank: Quartermaster.

During his 19 months of service in the Pacific during World War II, Diaz de León served aboard the USS Connor, a destroyer. He recalls witnessing kamikaze attacks, the death of his captain and rising to the rank of Quartermaster Third Class, an accomplishment of which he’s very proud, especially considering the high school dropout was competing with more educated peers.

The Connor, with a crew of about 300, was the second naval ship to be named for Commodore David Connor, who led U.S. Naval forces in the Mexican-American War. By the time Diaz de León boarded ship, the Connor had already bombarded Nauru Island, screened for air strikes on Kavieng, New Ireland, and made assaults on the Marshall Islands.

Diaz de León was serving just in time for the battles on Palau, Yap, Ulithi and Woleai in the Caroline Islands. In February of 1945, the Connor was part of the battle group at Iwo Jima, one of the bloodiest and best known of the WWII battlegrounds.

Like a number of minority WWII soldiers, Diaz de León fought two wars: one against the Japanese and one against the racism and discrimination of fellow Americans. For example, he recalls being put on report several times for offenses such as singing songs in Spanish instead of English.

Quartermasters, who help in steering the vessel, frequently spoke to the entire ship over the loudspeaker. One day, Diaz de León made these announcements. And the next day, a group of fellow sailors asked if he’d been the person talking over the loudspeaker. With pride and a sense of accomplishment, Diaz de León answered yes, anticipating congratulatory remarks.

Instead, he says he received racist insults. Apparently, at one point he’d said, “darken sheep” when the message he meant to convey was, “darken ship.”

Diaz de León recalls a superior officer on the ship hearing about the incident and standing up for him. The superior then struck a bargain with the new Quartermaster: He would teach Diaz de León better English pronunciation, if Diaz de León would teach him conversational Spanish. The lessons went on for a little more than a year, Diaz de León says.

The USS Connor was in Jinsen, Korea and China in September of 1945, when the war ended in the Pacific. For the next four and a half months, the Connor was part of the Allied occupation of the Far East. Then, on Jan. 20, 1946, the ship was back in American waters and decommissioned in San Francisco, Calif.

“The ship has twelve battle stars and I know that I proudly earned about seven of those,” said Diaz de León, who was 20 by the war’s end.

Diaz de León returned to Martin High School and graduated in the veterans’ group. He then enrolled at Drake University in Des Moines, Iowa, where he earned degrees in sociology and psychology. Next, he earned his master’s in social work at Our Lady of the Lake University in San Antonio, Texas, in 1954.

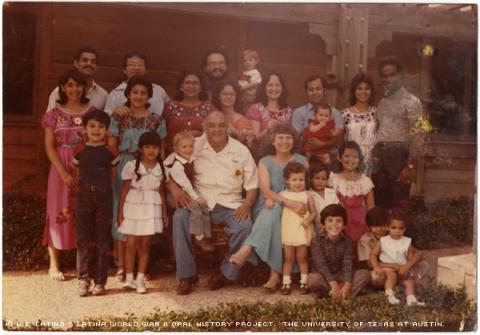

Diaz de León, his wife Josefina Villarreal Diaz de León, and their children eventually moved to Brownsville, Texas, where he worked as a senior child welfare worker. He also worked at Sears to support his family.

Diaz de León recalls learning of a higher-paying assistant supervisor position available in nearby Harlingen, and repeatedly asking his boss about the job. Then, Diaz de León says Reynaldo Garza, a lawyer who became the first Latino federal judge in American history, told him that those hiring wanted an “Anglo.”

Dejected, Diaz de León began looking for a new job.

“And that’s how I ended up in a more racist community, in Kingsville, [Texas],” he said, adding that it was the eye-opening experiences of racism and poverty there and throughout his life that led him to protest for social change.

Diaz de León became active in the American Indian Movement, serving as Laredo’s first Community Action Agency Director in 1965, and working with the Colorado Migrant Council. He also became active in the Chicano Movement, an integral part of the Latino Civil Rights Movement’s fruition and growth. He ran for U.S. Senate in 1978 on the La Raza Unida ticket, loosing with 18,000 votes.

After a lifetime of struggle and achievement, Diaz de León wants the younger generation to continue carrying the torch for social justice and equal treatment, so the Texas of his grandchildren’s generation is different from the Texas he knew.

“Hopefully,” said Diaz de León, “our country moves in the direction of better education, better health services, better economic well being.”

Mr. Diaz de León was interviewed in Round Rock, Texas, on April 5, 2008, by Raquel C. Garza.