By Kelly Tarleton

The thought of failure has never deterred Leopold Rodriguez Moreno from his goals.

Moreno says he was the first Mexican American to be sent to West Virginia as an inspector for the Southern Pacific Railroad Co.

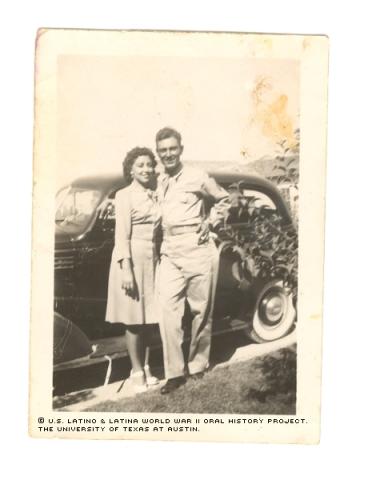

He met Rosa Villagomez, the woman of his dreams, and decided he’d marry her. Six years later, he did.

But Moreno says one of his most important accomplishments is having survived a gunshot wound in the back during the Battle of Luzon in World War II.

He recalls seeing a half dozen fellow soldiers falling dead around him as they were charging up a hill. He quickly surmised the shell that ripped into his back had been a ricochet, penetrating his body only slightly. The American forces won the battle and Moreno was later awarded the Purple Heart for his wounds on the battlefield that day.

According to Moreno, so many high-ranking officers were killed in the battle he was promoted to sergeant afterward.

Moreno's pride shows when talking about his life's triumphs.

"If I don't make it, at least I tried," said Moreno of his philosophy of life.

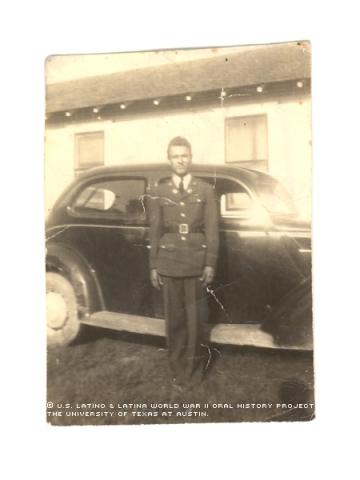

Moreno was born August 8, 1923, to Leopold Moreno and Dolores Rodrigues Moreno in Beeville, Texas, about 100 miles southeast of San Antonio, Texas. He graduated from Sam Houston High School in Houston in 1943, and enlisted in the U.S. Army shortly after graduation.

Moreno completed basic training at Camp Roberts in California in the summer of 1943. He was shipped to the South Pacific, spending 21 days at sea before landing in New Georgia in the Philippines. As a member of Company A of the 169th Infantry Regiment, 43rd Infantry Division, his unit helped secure New Georgia and then participated in the Battle of New Guinea.

Moreno seldom talks of his fears when recalling his life during the war. He recalls the trip to the Philippine Islands, assaulting them on Jan. 9, 1945, at Lingayen Gulf. When talking of his war wound, he relates to it almost casually, if at all.

"It wasn't a severe wound, but just bad enough to get me out of the front lines," he said.

The Battle of Luzon was fought in January of 1945, under the command of General Douglas MacArthur, after the Allies' successful invasion of the Leyte Islands in the Philippines. The battle was essential in gaining U.S. control of the Pacific Theater because it6 was among the largest northernmost Philippine islands.

After spending time in a Manila hospital, Moreno was returned to his outfit, but didn’t know anybody in the unit.

"I thought I was in the wrong place," he said.

Most of Moreno's friends had been killed. Later, he sustained serious stomach ailments that forced his return to a military hospital. He never went back to battle. Moreno returned to the U.S. in July of 1945 and was discharged that November.

He says he was aware of little, if any, discrimination against minorities during his time in the Army. Perhaps, he says, it was obscured or lessened by all the death and destruction around them.

Before meeting his wife, Rosa Villagomez, in Houston, Moreno recalls telling a friend, "I gotta meet her!" The friend warned him about her big boyfriend, but Moreno wasn’t deterred.

He married Villagomez on Sept. 16, 1945, while on a 30-day leave.

His face lights up as he describes the initial time he saw the woman who’d be his wife. The first time they met was June 29, 1939, at a neighbor's party when Moreno was 16 and Rosa 15. They kept in touch by writing letters, and married shortly before the war ended.

"We share things," said Rosa, a first-generation Mexican American, of her and Moreno’s marriage. "So many young marriages don't do things together."

Moreno says one of his proudest moments is the day he helped open the door for minorities while an employee at the Southern Pacific Railroad Co.:

There was "a lot of discrimination in those days," he said. For example, no blacks or Mexican Americans were allowed to go to other states for freight-car inspections, says Moreno, adding that he didn’t accept this barrier.

After climbing the employment ladder from apprentice to journeyman to inspector, he went to his union representative and requested something be done about the practice: He was soon sent to West Virginia to inspect cars.

Moreno traveled to West Virginia with an African American man, the first black man to be sent to inspect cars. The two formed a pact.

"We got to set an example for other guys," Moreno recalled telling a friend.

The two succeeded in gaining praise from their manager and helping other workers gain overtime. Their manager, Moreno says, wrote a letter to upper management commending Moreno and his colleague on their superb work and ability to catch every flaw in the line.

"I opened the doors!" said Moreno, recalling the proud moment he experienced after hearing of the letter.

Overcoming racial adversity in the workplace increased Moreno's confidence. He remembers his self-esteem and confidence being low while in high school. For example, despite being a member of ROTC in school, he remembers thinking he couldn’t make much of himself.

The tell-tale signs of a different time and era while he was growing up probably didn’t help: He remembers seeing a sign posted at a restaurant reading, "No dogs or Mexicans allowed."

Almost 40 years after WWII, Moreno became a church deacon in 1984, continuing at the time of his interview to work at the Catholic Charismatic Center in Houston, Texas.

Today, he lives with Rosa in Houston. Their nine children are grown and they have 15 grandchildren.

Mr. Moreno was interviewed in Houston, Texas, on August 8, 2003, by Paul R. Zepeda.