By Alison Kelley

Lazaro Lupian doesn't think his accomplishments during World War II were a big deal; the only true war heroes, he says, are the ones that don't come back.

Some would disagree, especially family members who still remember reading in the San Diego Union on April 21, 1945, that a small town in Germany had been named Lupianville in honor of their son. But even more than having a town named after him, this 79-year-old veteran takes pride in his own California home and family. He sees his experience during the war as a modest part of the Lupian family tradition of service and discipline.

Lupian's father, Jose Serrano Lupian, served in the Mexican navy from 1916 to 1923. That year, when he got out of service, he and Lazaro's mother, Manuela Miranda Lupian, moved with their 1-year-old son to California in search of Mauela's sister. Once they found her, the family settled in San Diego, making a permanent home.

Lupian said his father never spoke much about his experiences fighting for Mexico when he and his sister Sara were growing up, but by example he taught them about discipline and responsibility.

Lupian remembers his father working any job he could find in order to provide for the family – everything from ditch digging to bartending. However, most of his father's life was spent working at the U.S. Grant Hotel, where he went from washing pots and pans to serving as maitre d'.

"He was a good-looking man and his accent worked well for him," said Lupian, speaking of his father's charm, which endeared hotel guests such as presidents Roosevelt and Hoover.

Lazaro's mother, who was born in June of 1889 in Sinaloa, Mexico, was also well respected. In their Latino community in San Diego, she was known for her generosity, ingenuity and good cooking. Manuela was one of the first entrepreneurs to open a Mexican restaurant, "Mi Casita," in the barrios of San Diego. She was the restaurant owner and the cook throughout her life.

"She was a good cook and her food was well-known," said Lupian, telling how during the depression she would often feed the field workers. "If they had money, they paid for lunch. If they didn't, the workers still ate lunch."

"When I was a school kid, I would trade the taquitos she gave me for my gringo friends' peanut butter sandwiches," Lupian said.

During his school years in the late twenties and thirties, San Diego had thriving Japanese, Mexican and Italian communities.

"I never had a Mexican teacher, but I really don't remember much discrimination in school," Lupian said.

He said he didn't perceive racial prejudice until before graduation, when school counselors told him he wasn't qualified to go to college because he hadn’t taken the necessary classes. He wondered why they didn't tell him which classes met the college qualifications when he first started school.

Lupian said he didn't dwell on that, however. After graduating from San Diego High School in 1941, he got a job at the Grant Hotel, where his father worked, and where he learned how to be a butcher.

A year later, in December of 1942, Lupian was driving down Highway 101 on the way to see his girlfriend when he heard from the crackling car radio that Japan had bombed Pearl Harbor and that America was going to war. He wasn't a U.S. citizen, so he didn't think much about this either.

"You can imagine our surprise when we were the first ones to go," said Lupian about him and his Latino friends, "We weren't even true citizens."

Lupian said some of his friends dodged the draft, and even his father encouraged him to enroll in the Colegio Militar in Mexico, as a way of avoiding the war.

Although his parents didn't want him to leave, 20 year-old Lupian decided serving the country was something he needed to do. When he left for training in the beginning of 1943, his father left him with a final admonition – don't disgrace Babylon, or, in other words, behave.

Lupian and the 385th infantry regiment arrived in South Hampton, England, in November of 1944. From there they moved to Luxembourg, where he first went to battle. As he described it, their unit's assignment was to "fight through the Sigfreid line."

The soldiers had to penetrate Germany's front lines in a mechanical march of tanks, which moved only 10 or 15 miles a day. As part of the fortification, the German's had set up dragon teeth -- huge cement blockades that would impede the tanks. Around them were areas called pillboxes, and it was from these posts that German soldiers would attack with ammunition. Ground troops like Lupian’s would have to capture the pillbox before the tanks could advance.

"Look out for yourself was the first thing I learned," Lupian said.

It was a lesson he learned the hard way.

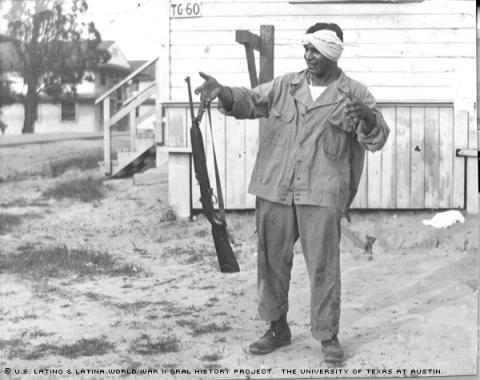

On February 20, he was hit in the arm by shrapnel while trying to capture a pillbox.

His first reaction to the hit was a sigh of relief, as he thought he’d be going home, and he wouldn't be in danger any longer and wouldn't have to see death anymore. He thought wrong.

The injury turned out to be minor, and Lupian was back in the battlefield within a couple weeks. But fate struck again a month later.

By then, Lupian had become a sergeant staff officer. On March 30, when he and one other soldier were on a reconnaissance assignment along the banks of the Rhine River in Germany, they came upon a small town of 10 or 15 homes. Turns out, it was a small town with big surprises.

"It was supposed to be a reconnaissance patrol, but it turned out to be a combat mission," Lupian recalled.

Two German officers had been hiding out in the village. When they saw the two U.S. troops, they both opened fire. Lupian shot back. One German soldier was hit; the other surrendered. Having taken a hit in the leg, Lupian was sent to Paris for medical treatment.

Other Allied troops arrived and captured the little village, where it was believed more enemy troops had been hiding in a coal mine. The town was named Lupianville, in honor of its captor.

Lupian's parents read the account of their son's victory in the San Diego Union on April 21, 1945. It was good news. With the war almost won, the report meant it was only a matter of time before their son would return home -- and in their eyes -- return home a hero.

After his return, Lupian went back to work as a butcher at the Grant Hotel. He married Grace Elvira Gastelum in June of 1947. The couple eventually had four sons and three daughters.

Mr. Lupian was interviewed in San Diego, California, on December 3, 2000, by Rene Zambrano.