By Alan K. Davis

From their crippled B-24 bomber, Ladislao "L.C." Castro and the rest of the crew could see the white cliffs of Dover across the English Channel, on March 18, 1944. The fuel gauges read empty. The control cables were severed. And a 4-foot section of the left wing was missing.

The bomber began a slow downward spiral toward occupied France; there was no way to make it back to England.

When the orders came to abandon the bomber, Castro was the first out. With his leg torn and bleeding, Castro jumped through a hatch in the rear of the bomber. He watched the ground rush toward him as he fell feet-first. He pulled the ripcord and opened his parachute just above the treetops. Then he was on the ground.

Castro was in enemy territory with nothing to do but hide. For the next six months he would do just that.

Just over a decade earlier, Castro was riding around Austin, Texas, on top of his father's cart, from which they sold tamales. In those days, he would never have dreamed of riding in an enormous four-engine bomber, much less jumping out of one from 10,000 feet in the air.

Castro's memories growing up in Depression-era Austin are of happy times in school, first in Catholic school at Our Lady of Guadalupe, then in the Austin public schools. In high school, he decided what he wanted to do with his life: he would be an auto-mechanic and working on cars became his hobby.

Then the war intervened.

"In '42 I graduated from vocational school the first of June. And in November the war was getting pretty heavy in England," Castro said during a recent interview at his North Austin home. "About November, I volunteered to go into the service, in the Air Force."

Castro's Mexican-immigrant parents, Ladislao and Leonarda (Oseguera) Castro had eight children - two girls and six boys. Four of the boys would fight in the war, spread out around the world from Burma to Belgium.

With his background in auto mechanics, the Army Air Corps-later to become the modern Air Force-assigned the 18-year-old Castro to training as an aircraft mechanic in the Tactical Air Command, where he would work on troop carriers. But service on the ground did not last long for Castro.

"They had a big call that they needed mechanics for the bombers," he said. "So I volunteered to be a mechanic on a bomber."

Castro became a staff sergeant and joined the crew of the "T-Bar," a B-24 Liberator, as an assistant engineer and aerial gunner. They deployed to England in October 1943 to take part in the 8th Air Force's bombing campaign against Germany.

The crew joined the 506th Squadron of 44th Bombardment Group (Heavy), nick-named the "Flying Eightballs." They began flying combat missions in November. Castro manned one of the big .50 caliber machine-guns in the waist of the B-24. He became accustomed to the long hours of monotony and physical strain on a typical mission.

"We did all our flying at the (open) side windows standing up," Castro said. "We had to stand up six, eight, ten, even 12 hours... The wind would be coming in...it got pretty cold."

Castro's third mission was one of the coldest. The mission, part of a series of raids intended to knock Germany out of the race to build an atomic bomb, aimed to destroy a plant in Norway that manufactured heavy water. The plant was Germany's only source of uranium.

When the bombers turned back toward England, they left their targets severely damaged. Castro's crew made it out of Norway-but on the return journey, Castro's heated flying suit failed, subjecting him to blasts of frigid wind through the open window of his gunner's station.

"My hands were real cold... I got frostbite all over my face," he said.

Castro spent two weeks in the hospital while his severely frostbitten face and hands healed. When he recovered, Castro flew 18 more missions.

Castro's 21st and final mission, an attack on the southern German city of Friedrichshafen near the Swiss border, ended with Castro and his ten fellow crewmembers abandoning their bomber within sight of the shores of England.

During the group's first pass over its target, an aircraft factory, a rookie group of B-17s arrived at the target at the same time as Castro's B-24, but at a lower altitude. The mishap prevented Castro's group of B-24s from releasing their bombs. The group, then, was forced to make a second pass over the target, according to the historical records of the 506th Squadron, in a self-published book entitled "The Green-Nosed Flying 8-Balls."

When they returned to the target at the same altitude and speed, the German anti-aircraft gunners had zeroed in on the B-24s: a black cloud of bursting "flak," anti-aircraft fire, erupted in their path. Almost every bomber was hit. One by one, bombers fell out of formation. Some crashed in Germany; others tried desperately to make it just across the border to neutral Switzerland, German fighters working them over with machine-gun and cannon fire all the way. Eight bombers from the 44th Bomb Group never returned to England, half of them from Castro's 506th Squadron.

A stream of fuel sprayed out of the plane. With the remaining fuel they could just make it, but they could not keep up with their group, either at the same altitude or speed. They dropped out of formation and called for a fighter escort.

"The pilot asked if we wanted to try and make our way back to England," Castro said. "We decided we should try."

Switzerland was close. They could easily land there, but landing there meant internment until the end of the war; at the time there was no end in sight.

The crew tried to preserve fuel by lightening their load: they dropped guns, ammunition, protective "flak" suits and other excess gear out the windows of the struggling bomber. They flew nearly the entire width of France, avoiding areas where they suspected anti-aircraft guns.

But their luck ran out as they attempted to cross the French coast.

A single, slow bomber flying at medium altitude proved an easy target for German gunners: shell after shell burst around the B-24. The aircraft filled with holes as white-hot pieces of shrapnel tore through the bomber's aluminum skin. One piece ripped through Castro's right leg, leaving his calf sliced open and bleeding. The crew could not save the aircraft. The pilot ordered them all to bail out. When he jumped, Castro was already resolved not to become a prisoner of war.

"I didn't open my parachute till I was real close to the ground," he said. "Made it hard for the Germans to see me. When I hit the ground, I hit it real hard going sideways and broke my [right] leg."

Castro gathered his parachute and hid it, then limped away in search of cover. Looking up, he saw the other crewmembers coming down as a group, having opened their parachutes right after jumping. The Germans were shooting at them as they drifted helplessly downward. With gunfire so close, he hid in a nearby haystack.

When the Germans picked up the other crewmembers and discovered only nine of the B-24's 10-man crew, they returned to the fields to search for the missing man, Castro. According to historical accounts of the squadron, the other crewmembers became prisoners of war. Castro, however, began life as an "evadee," a term given by military officials to airmen who eluded capture.

From inside the haystack, he could hear the Germans looking for him.

"There was this one German, he had his rifle and he went poking into all the haystacks," he said. "He poked into the one I was in and I could almost feel the bayonet on the rifle as it went right by and missed me."

Castro was finally discovered the following morning -- not by the Germans -- but by a small French dog. The dog barked and ran circles around the haystack, drawing the attention of French villagers nearby. The villagers helped Castro from the haystack and hid him in a barn. There, over the night, they fed him, clothed him, and brought a doctor to treat his wounds.

Despite his crippled leg, Castro journeyed by foot and bicycle for the next several days to the city of Amiens. In a time of shortages for the French people, they always found food for him. French men and women again and again took risks to guide him to safety, knowing that they could be executed for helping an Allied airman evade capture.

Castro was moved from house to house until the French Underground, the resistance movement in France, picked him up and took him to an old woman's home in Amiens where 16 other allied airmen were in hiding. For almost five months Castro lived in this house, sleeping in a single room with the other evadees. There was little for the men to do but rest. Slowly Castro's fractured leg healed.

During this time, Amiens was under constant air attack by the Allies. American bombers were a common sight over the city and Castro recalls watching attacks on a regular basis.

"One time these P-51s came over...and bombed the heck out of it," he said. "Those guys were darned good, because if they dropped one just a little bit short, they would've knocked our wall down and we'd be out in the open."

When the Germans retreated from Amiens in the face of the advancing Allied armies, Castro and the other evadees celebrated in the streets with French resistance fighters. The Canadian Army liberated Amiens on September 1st, 1944. Castro put on a Canadian uniform and traveled back across war-ravaged France to a captured German airfield. He was flown out on the next available flight.

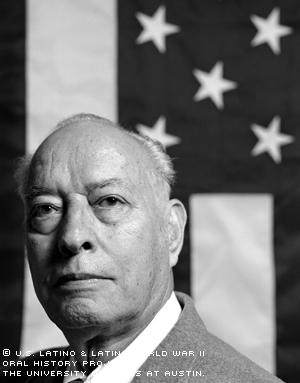

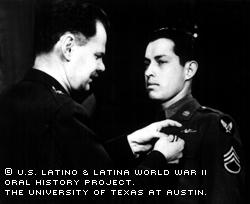

Castro returned to the United States to undergo debriefings on and questioning about his time spent behind German lines. After two weeks of rest and recreation, he was stationed at several bases around the U.S. before being discharged from the military on October 30, 1945. When he left, he wore the Air Medal with three Oak Leaf Clusters and a Purple Heart on his chest.

Life after the war proved to be very different from Castro's pre-war expectations. He attended college on the G.I. Bill, studying business while working at an Austin post office. After seven years with the postal service, Castro began a successful 22-year career as an accountant at Austin's Bergstrom Air Force Base, the same place he enlisted to fight in World War II almost 50 years earlier. Castro retired from Bergstrom in 1989.

In 1948, Castro married Sallie Castillo and the couple would have two sons, James and Juan.

Military service did not end for Castro at the closing of the Second World War. A member of the Air Force Reserve, he was recalled to active duty as an aircraft mechanic during the Korean War.

The tradition of service continued through the generations of Castro's family: James Castro is also a veteran. He served as a medic in the Air Force during the Vietnam War. His mission: rescuing downed American pilots trapped behind enemy lines.

And only ten years ago, a third generation of Castros was called off to war. James Castro's son, James Jr., served in the 1991 Gulf War.