By Jocelyn Ehnstrom

As a young kid, Julius Moreno enjoyed playing baseball, tending to his family’s farm animals at their home in San Antonio and singing in his neighborhood band called “The Holly Boys.”

But the first priority of Moreno’s father, Julio Moreno, Sr., was making sure all nine of his children, the second oldest of whom was Moreno, got a good education.

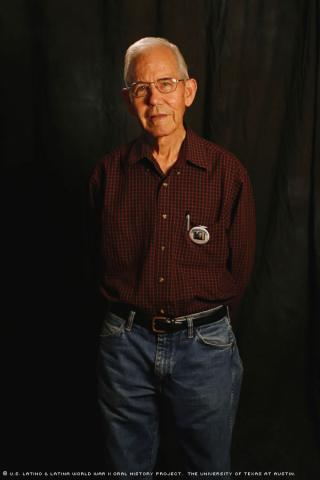

“We had a deal that he wouldn’t take us out of school to help the family with money, as long as we graduated from high school,” said Moreno, sporting a maroon shirt the same color as his alma matter Texas A&M.

“My father was always very anxious to help us out because school was very important to him. Each month he’d line up all of us children and one by one ask if we were having any problems,” he said.

Moreno recalls one month in which he and his siblings were having problems understanding fractions, so Julio found a neighborhood boy to tutor the family.

“I’m not sure what the arrangements were exactly, but for two months that boy helped us until we all understood.”

It was the importance his father placed on education that got Moreno and all nine of his brothers and sisters through the various grades, each graduating from Boliny High School in San Antonio.

Growing up, Moreno says he ignored most of the discrimination he encountered, which occasionally caused him grief, but wasn’t as bad as the discrimination directed toward African Americans, who had to attend separate schools.

“I only had one Hispanic teacher during elementary school,” Moreno said. “There just wasn’t a lot of togetherness. We ignored the Anglos and they ignored us.”

Moreno graduated in 1942. Because he was only 17, he worked in the neighborhood laundry for a year waiting for the day he could sign up for the war. In January of 1944, he enlisted in the Army Air Corps with aspirations of becoming a pilot.

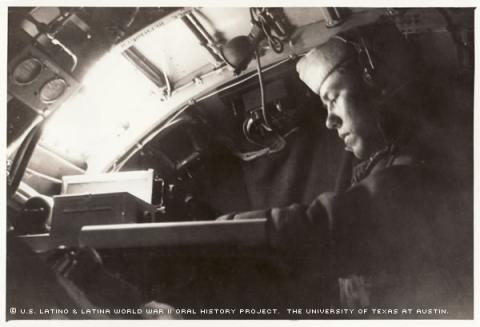

Although it turned out his test scores weren’t high enough for him to qualify to be a pilot, the military offered him a job on a B-24 Heavy Bomber as a gunner with a flying-radio operator specialization. He received aerial gunnery training at Yuma Air Force Base in Yuma, Ariz., radio training in Sioux Falls, South Dakota, and then training with the 15th Air Force Division for three months at Topeka Air Force Base in Topeka, Kan.

“[W]e all grew very close, and really began to resemble a unit,” said Moreno of his time in Colorado.

To get to Italy, his crew flew from Newfoundland, Canada, over the Azores Portuguese islands, past England and into mainland Europe. Moreno recalls many people thinking he was of Italian ancestry in Italy, and he found being bilingual in Spanish perpetuated this misconception.

“The languages are very similar, and it also helped that I could pick up on the tonality of conversations,” he said.

His crew was assigned to Special-Forces Squadron 859 in Southern Italy’s Cerignola. Their job: to fly in support of friendly “underground groups” against Nazi-occupied forces in Europe. The carpet-bagging mission with the Office of Strategic Services included fly-by-night missions into Germany, Austria and the Czech Republic, where he and his crew would distribute pro-American propaganda leaflets to spies by dropping them like bombs over the country, Moreno says.

“This was a supersecret ‘underground groups’ support [job],” wrote Moreno after his interview regarding his crew’s classified activities. “This was [all] finally released some 10 years after the war.”

Leaflets weren’t the only items they distributed. Moreno says they also brought supplies and bombs to any area where more than fifty allied soldiers were stationed.

“It was kind of like detective work,” he said. “It was also very dangerous, because we flew at night so we never knew who were the people signaling us. You were always just hoping it was a friendly guy.”

One time, their aircraft was boarded by a group of Russian soldiers, who Moreno understood were simply carrying out their own orders. He remembers the two groups politely nodding toward each other, and the Russians being very serious.

It was during this time he met John Carr of Boston, who was his co-pilot and best friend during the war. The two men have remained in touch through phone and computer, and even reunited in Las Vegas 48 years after last seeing each other.

“All I had was a photograph of the two of us 48 years younger, but when I saw him, he looked at me and I looked at him, and we both recognized each other,” Moreno said.

A lucky man, he returned home from the war as an uninjured staff sergeant. He began classes at Texas A&M University, where he got a degree in industrial engineering and soon met his future wife, Alice Herrera, to whom he’d been married for 54 years at the time of his interview. They have a daughter named Sandra.

“All nine of my brothers and sisters have only one or two children,” Moreno said. “I guess we learned growing up.”

Working as an engineer for Kelly Air Force Base the past 35 years, Moreno enjoys helping the poor by volunteering at San Antonio’s Christian Assistance Ministry and remaining active in his church, Covenant Presbyterian.

He credits his parents with being the driving force behind his and his siblings’ success and closeness, through prayer, as well as through orchestrating elaborate family reunions well into their old age.

Mr. Moreno was interviewed in San Antonio, Texas, on August 4, 2007, by Anna Flores Peña.