By Joseph Money

Joe Autobee, of Publo, Colorado, grew accustomed to the taste of whiskey during his WWII service. As an Air Corps gunner pilot during World War II, he was given a sandwich and a glass of whiskey at the end of every raid.

While Autobee wasn't sure how the service had made their choice of refreshments, he took it just the same.

"I think whiskey's good for your nerves," Autobee guessed.

In all, he flew 21 missions in the European Theater. But none, perhaps, was as significant as his last. Autobee served in the Eighth Air Force, the last force to bomb Germany during the war.

Though history may acknowledge the significance of forces like the Eighth Air Force, the story of the men who made that team is just as important. Men, like Autobee.

He was born Joseph Marion Autobee on Feb. 16, 1924, to Sophia and Francis Macario Autobee, and was raised in the small town of Avondale in the Rocky Mountain state. Able to speak both English and Spanish, Autobee believes he grew up with an advantage over other Hispanic American children.

Remaining in Avondale through his teenage years, he graduated from Avondale High School in 1942, after America had entered into the Second World War. Not long after high school, Autobee moved to Wichita, Kansas, to become a sheet metal mechanic. He said the move was an obvious one.

"I have a diploma in one hand and I was washing pots and pans with the other one," Autobee said.

The move would be short-lived, however, as Uncle Sam would soon come calling. Autobee and the high school friends he moved with returned home.

"In [those] days...two weeks after you received your [draft] card, you went to the induction center to be inducted," Autobee said.

This time, it was not to be. Autobee was one of a few not called in that induction. But his entry into the war effort would not be denied.

Autobee and his brother went to work at the Pueblo Army Air Base in 1943. In order to make a little extra money, Autobee coupled the base work with a farming job. But these endeavors proved to have the shelf-life of Wichita...the Armed Services decided they were ready for Autobee's help.

The small town kid from Colorado soon became a world traveler.

Autobee began his journey at Fort Logan, Colorado, and it was there that he was formally introduced to life in the Air Corps.

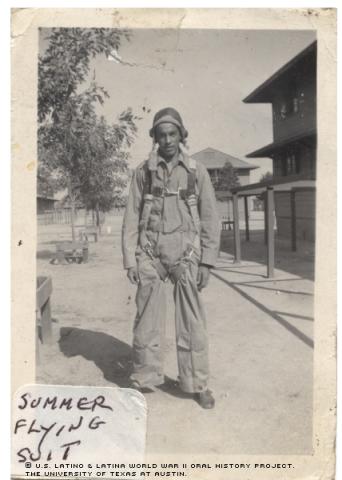

Over the next year-and-a-half, Autobee's U.S. travels included Colorado's Buckley Air Field for basic training. He then moved on to gunnery school in Arlington, Texas before finally being transferred to Lemur and March Fields in California for flight training. Autobee remembered being scorched in the southern parts of the Golden State.

"At 500 feet it was so hot, and I mean 500 feet over the Mojave Desert in the summer," Autobee said.

His last U.S. stop was Fort Taunton near Boston. New England, however, was only a two-week stay. Finally, on Dec. 18, 1944, Autobee and his comrades touched down in Liverpool, England. It was time for the real thing.

All the while, Autobee never regretted his journey or his drafting.

"No problem because we were one of the last ones out of here [at] our age," Autobee said.

He took his place in the Eighth Air Force. The Second Air Division, 448th Bomb Group to be exact.

The mission for the bomb group was simple: bomb the target. For Autobee and soldiers of the Eighth Air Force, the mission was trickier. After 35 missions were complete, you went home.

According to Autobee, many men volunteered for as many missions as possible. The faster they went, however, the faster they got out. Autobee decided to take a different approach.

"Not me," he said in an interview at his home in Pueblo, Colorado. "I took my time. I didn't volunteer. I went as a tail gunner with this other crew because they told me to."

Ordinarily, Autobee served in his B-24 Bomber as a top turret gunner. It was his favorite position because, as Autobee describes, one could see almost anything.

"I could see where the bombs hit," Autobee noted while describing his viewpoint.

His viewpoint enabled him to keep a book describing his mission; a keepsake that remains in his possession today.

Reading the book, Autobee vividly recalls every mission. The temperature, altitude, ammunition, target and time spent over Germany all recorded in his journal. The opposing gunfire, or flak, was also noted in every entry. In fact, that flak also helped Autobee keep track of another book.

"I had a little prayer book I carried with me all the time," he said. "It's in my bedroom drawer."

Autobee also said the war helped him become a more religious person. His commitment to Mass is one example.

"I don't hardly miss," he emphasized.

Throughout all the missions, the flak and the emergency landings, Autobee also kept one other value sacred as well. Friendship.

Autobee communicates via postcard with other airmen from Illinois, Texas and California. In 1984, he began an eight-year search for two men he lost track of after their U.S. training together. In 1992, at the Norwich Memorial Library in England, he finally found the records of his fallen patriots. They were shot down during their first mission.

After the war's end in 1945, Autobee returned to the States but maintained his commitment to the Armed Services. He was stationed in Connecticut and Nebraska before being formally discharged. Autobee and a friend hitchhiked from Lincoln to Denver. Upon finally coming to Pueblo, and even turning down an Associated Press job in Chicago, Autobee became Foreman of the Pueblo Army Depot and stayed there for over 36 years.

Even though Autobee kept his commitment to his country, there were times that he felt his country never kept its commitment to him and his people. Though the enemy of Nazi Germany was defeated abroad, the enemy of discrimination was still felt at home.

"It's always there but it's hard to prove," he said.

Less hard to prove is the service given by Hispanic Americans like Joe Autobee during World War II. While the Air Corps gave any serving American his whiskey after a mission, people of color still couldn't drink from certain fountains at home. Autobee's dedication to his country has already made him a hero of war. The next question is whether or not his story, and those like his, will make war-generation minorities heroes of culture.