By Andrea Shearer

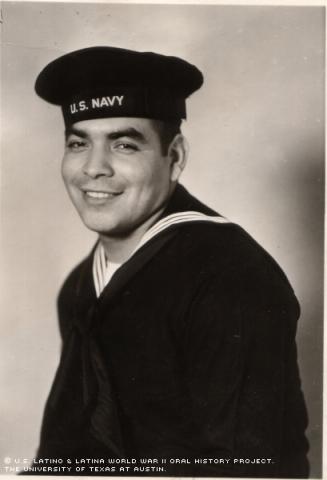

While the USS Gleaves Destroyer Escort was cruising the waters of the Philippines, Jose Ramirez was high up in the poop deck, looking for signs of the enemy through the scope of a 44-mm anti-aircraft gun. In quieter moments between battles, Ramirez was filling requests for Spanish serenades.

"They'd say, 'Come on Joe, sing that song again while some of us go to sleep while you're singin,'" he recalled.

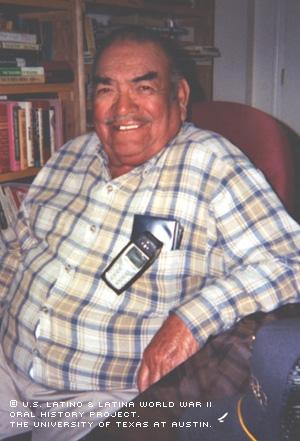

At an interview at the veterans' center in El Paso, Texas, Ramirez sang a few bars of one of his favorites, the old Mexican ballad "Solamente Una Vez."

Before Ramirez was born, his parents, Pascual Ramirez and Catalina Solis Ramirez, had been ranchers in Zacatecas, Mexico. They were forced to leave their homeland when Mexican revolutionary Pancho Villa and his men threatened to destroy the family's estate if Pascual didn’t join them in their fight. So Ramirez's father decided to cross the border into El Paso, leaving Mexico and the bandits behind, and sending for his wife and children.

On March 27, 1918, only two weeks after Catalina arrived from Mexico, Ramirez was born.

"Like I'd tell my mom: I think I was paddling the water while you was crossing!" he said.

The family moved continuously as they followed Pascual’s work in fields and on railroads from California to Wyoming.

Wherever they were, the Ramirez family remained true to their roots: They threw parties to celebrate Cinco de Mayo (5th of May) -- which commemorates the battle of Puebla, Mexico -- and Dieciseis de Septiembre (16th of September), which marks Mexico's independence from Spain.

Although only Spanish was spoken in the Ramirez household, English was spoken at school.

"I remember I was in a school in Kiowa, Kan., and I was sitting in this desk that didn't have no desk in front, just a chair. And there was a white girl behind me, beautiful girl." Ramirez recalled. "I didn't know what to say. I didn't know how to speak English then. ... She used to pull my hair ... I wouldn't even look around, just let her pull my hair. 'Til one day she says, 'You know, my name is Gail,' and I said, 'Ok, me Jose.'"

Ramirez learned English quickly.

"We never spoke any Spanish, once we got going to school. My brothers and friends, we all spoke English," he said.

Ironically, years after he had forgotten the Spanish of his childhood, the family moved again, this time to Juarez, Mexico. Now an adolescent fluent in English, he was suddenly faced with not knowing enough Spanish.

Although he experienced some prejudice in his childhood, his proficiency in English partly shielded him from discrimination, both economic and cultural. Because he spoke the same language as his Anglo foremen, they favored him and gave him a job as Assistant Engineer on a road project, for which he chose to leave his studies.

That newfound social status also helped shield him against taunts from fellow Mexican Americans who’d mocked him for his deficiencies in Spanish. Suddenly, they showed him deference.

By the time the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor, Ramirez was married and had two children. His first wife was Elenor Aldana. After that relationship ended in divorce, he married his present wife, Refugia Ayala Ramirez.

"I remember my brother and I, we was home listenin' to radio. My li'l boy Robert, he was a li'l' baby and I had him in a crib. It was cold outside and all of a sudden the radio stopped playin' songs and we heard President Roosevelt announce that we were at war," he said. "We felt pretty bad, but we couldn't do anything 'til we got called to go to the service."

Ramirez enlisted in the waning days of the war. Aside from a minor attack on the USS Gleaves destroyer escort, where he was part of a 75-man surveillance crew, Ramirez saw no combat.

A torturous assignment as a foot soldier in the hot tropical sands of the Philippine island of Mindanao made him appreciate his later job on the USS Gleaves, he remembers.

"We were all just like a family," he said. "Even the captain would sit down and eat with us."

Seaman 2nd Class Ramirez was honorably discharged on March 3, 1946. After the war, he returned to Cheyenne, Wyo., and immediately took his family to visit Mexico. Then he returned to the railroad, where he became Foreman.

"When I came back, I bumped 22 guys to get the job that I wanted. And that didn't sit too well with the ones I had to bump!" he said.

In spite of some confrontations with jealous co-workers, Ramirez became active in his community.

"I used to tell the rest of the veterans, the Mexican boys, "Why don't you join the American Legion? It's good for yas!' And some of 'em said, 'Aw, who cares! They're a bunch of gringos!' So I told the commander, they don't wanna join your legion 'cause y'all are too many gringos here. So he says, 'Ok, well why don't you organize one for your Spanish people?' So I did! I got 15 guys, they paid their dues; we made the application and we got our license!" Ramirez recalled.

Ramirez would later become the first Latino policeman, deputy sheriff, and commissioner of streets and alleys in Cheyenne. He divorced in 1966 and returned to El Paso. Two years later, he met his second wife at a quinceañera in the West Texas city, where they still lived at the time of his interview.

Ramirez was pleasantly surprised by how much it had changed.

"When I returned, I found people different around here," he said. "The Latin people are noticing that they can come out and vote, be a candidate and have businesses, which they never could before. If it keeps goin' like that, the Latin people are gonna really be seen in this country."

Mr. Ramirez was interviewed in El Paso, Texas, on February 2, 2002, by Andrea Shearer.