When Jose R. Zaragoza returned from World War II, he found an invigorated Los Angeles ripe with opportunities for younger generations of Latinos.

Zaragoza was born in Los Angeles, Calif. in 1920. His parents had emigrated with his two older brothers from Mexico to escape the violence of the Mexican Revolution. When he was 9, his family moved to the flatlands of Northern California right before the onset of the Great Depression. Although he did attend school in California for a short time, he quit to work in the fields.

Many of the Anglo students looked down on their Latino counterparts, and it was understood that Latinos were the hired hands while the Anglos were the farm owners. "The kids . . . they didn't like Latinos too much . . . and they let us know," Zaragoza said.

The grinding effects of the Depression forced the Zaragoza family to return to Los Angeles, where he worked for a shoe-repair shop owner. Zaragoza made $6 per week, earnings which were contributed to the household.

"It kept you off the street," he said of the job. "And you were doing something useful."

When he turned 18, Zaragoza joined the Civilian Conservation Corps where he participated in community service projects such as rebuilding a California mission that had been damaged by earthquakes. He served in the corps for 15 months before returning to Los Angeles, and in 1940 secured a job at a meat packing plant.

The next year the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor. Zaragoza volunteered for the U.S. Coast Guard six months later.

"It's not like today, how people don't want to go," Zaragoza said. "Everyone was ready to go. Everyone was patriotic."

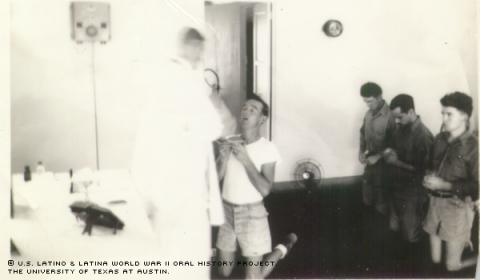

Once he joined the Coast Guard, he patrolled the Pacific coast defending against sabotage and invasion from the Japanese. Once the imminent threat of invasion waned, Zaragoza decided to go to radar school.

During his training, he received instruction in the then-emerging and secretive field of loran navigation. With his newfound skills, he was sent to Ulithi atoll, located between Guam and the Philippines, from where the Coast Guard and U.S. Navy tracked the movement of ships throughout the Pacific.

Loran technology - a term fashioned as an acronym for Long Range Navigation - is akin to radar work. Loran is a system in which pulsed signals are sent out by two pairs of radio stations, and are then used to determine the geographical position of a ship or airplane.

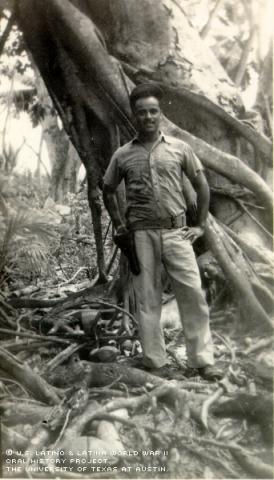

"I saw . . . different islands, got to mingle with the natives, things that I would have never dreamed of seeing if I hadn't went there and the war hadn't come along," Zaragoza, who eventually achieved the rank of radarman 3rd Class, said. "I wouldn't trade it for anything."

The Japanese held the Ulithi atoll, but later abandoned it when it was deemed too small and rugged for use as an airfield. With heavy equipment, American forces invaded the region and built an airfield suiting their needs. The United States flattened the largest island, using it for both and airfield as well as a naval port. Another advantage of the newly built station was allowing for the repair of ships without the need for a long trip to Pearl Harbor.

There were 25 men on the "navigation island" with Zaragoza. "It was like isolated duty. [It] gets kind of tiresome being there over a year," he said.

He served on Ulithi Island for 15 months. Despite being the only Latino on the island, Zaragoza had many friends.

Zaragoza's two older brothers also served during World War II. Zaragoza still gets emotional when he thinks of his mother's suffering, having three sons serving in combat simultaneously, not knowing from one day to the next whether or not they were safe.

"My mother," Zaragoza said, choking back tears, "to lose three sons at one time, taken from her. I guess she took it pretty hard."

One of Zaragoza's brothers immediately went into combat, and was sent home after an injury. The oldest brother, meanwhile, initially had tried to enlist as a pilot in the U.S. Air Force but was denied entry because he was not a U.S. citizen. He was later drafted into the U.S. Army and served as a medic in England.

Zaragoza received an honorable discharge in March, 1946, and returned home to his family in Los Angeles. "It's one of the best feelings you can have, and you know that the war's over and that you made it," he said.

After the war, life was different for Latinos, said Zaragoza. Latinos were able to get jobs previously unavailable to them before the war. Latinos also had the opportunity to receive a college education.

As an example, Zaragoza cited his cousin who took advantage of the GI Bill of Rights, went to college and studied engineering.

"If it wouldn't have been for the war, he wouldn't have had the opportunity," Zaragoza said.

Once back in Los Angeles, Zaragoza began to work at a brother's grocery store where he eventually would meet his first wife. When his brother sold the grocery store, Zaragoza returned to work at the meat packing plant until its closure in 1970.

He later performed electrical maintenance at the local community college until his retirement in 1982.

While he was working at the community college, he divorced the woman with whom he had four children. In 1976 he met the woman who would become his second wife. She had three children from a previous marriage and they had their only child in 1977.

Zaragoza is thankful for the opportunities his children have had. All four children from his second wife attended college. One of his stepdaughters received a degree from Columbia University, he noted with pride. Zaragoza believes that Latinos continue to benefit from post-war societal changes.

"Your memory's like a book. Pages are just going by and you think about all the experiences you've had," he said. "Especially the war years."