By Monica Jean Alaniz

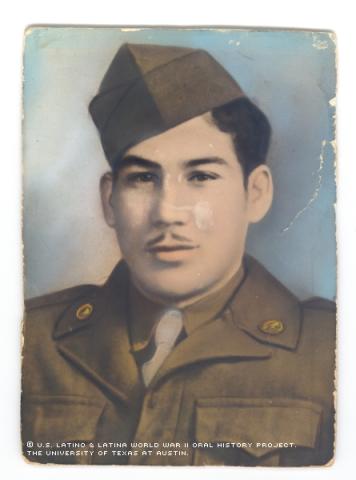

Jose Ramirez, Jr. is a man who holds his friends and family close to heart. One can hear the pride in his voice when he speaks of them; it doesn’t matter if they are part of his past or present. Ramirez looks back on his days as a soldier with mostly fond memories. He remembers buddies with a fond smile.

The period of time Ramirez served in the armed forces right after World War II ended is an important part of his life, but he’s humble about his experience. When asked for this interview he was hesitant, saying he "didn't see action."

His two older brothers did see battle, however, and they are his heroes. His second-oldest brother, Leonel, spent some time in a VA hospital after being wounded overseas. His oldest brother entered the war at the age of 16 after forging his parents' signatures. That brother, Leobardo, came back home suffering from shell shock. Memories of the war plagued him until his death in 1952.

Ramirez still has difficulty telling the story of his oldest brother's war experience. He explained that when Leobardo found out his younger brothers had been drafted, he questioned God, saying it was an "injustice to bring [him] back" only to take his brothers.

Leobardo cried in 1941 as his father made Ramirez board a bus returning Ramirez to his base after a short leave. Some of Leobardo's friends had tried to convince Ramirez he could go AWOL (absent without leave) and avoid going into combat, but his father wouldn’t allow that, Ramirez recalled.

Leobardo "was crying when he went to the bus. Hell, he was only 16," Ramirez said.

"I feel proud of my dad; I feel sorry for my brother," he added, when asked how recalling that incident makes him feel.

Having seen his brothers go off to war and the effects it had on them when they returned must have made being drafted especially difficult for Ramirez. He entered the Army in 1945 at the age of 18.

By the time he was drafted and went into training at Fort Sill in Oklahoma, the war was near an end. He was then sent overseas.

Ramirez was stationed in Japan about 6 months after the atom bombs were dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. He remembers the sight of these cities.

"You hardly could see anything standing. Hiroshima and Nagasaki was bad," he recalled.

He was one of three Latinos chosen to be drivers in a group of 11. The drivers' main responsibility was to transport troops from their docking sites to various strategic positions throughout Japan.

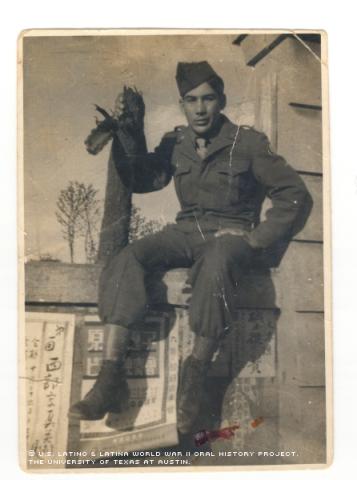

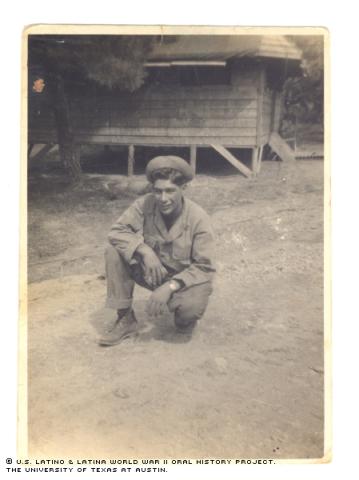

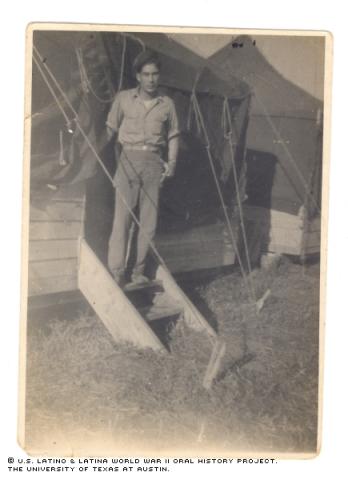

Ramirez's expression and words revealed fond memories of his time in the military, recollections further shown in photographs of him and his Army buddies.

One portion of a large, well-worn family album is dedicated to photos from his time in the military. Among old newspaper clippings and pictures of children and grandchildren are photos showing him with several other smiling soldiers. Whether they are by a body of water, relaxing after a swim or in front of a barracks, they are laughing, joking and look like they’re having a good time.

The faces in his photographs are those of Anglo and Latino men. According to Ramirez, they were all treated as equals and he experienced no discrimination. He recalls being especially close to a buddy named Benito Mancha.

"We [were] like brothers over there. We were very attached to each other," he said.

Ramirez kept in contact with Benito up until his death. He even flew to Chicago in 1997 to attend Benito’s funeral.

These men had a strong common bond: a deep-rooted love for their country. Ramirez said his family was proud of having him serve in the military; even though he was needed at home to help support his large family, "they just accepted [his serving] with no problem," he recalled.

In addition to being proud of those who served with him, Ramirez said he respects the Japanese people, especially their military tactics. He explained how they would hide airplanes and gasoline in the various mountains throughout Japan so U.S. forces would be confused as to where they were coming from. The Japanese would also construct decoy tanks and trucks out of lumber in order to trick U.S. forces into wasting their ammunition on useless targets.

Ramirez believes a lack of food and supplies, along with the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, is what finally caused the Japanese to lose the war.

Coming home was bittersweet for Ramirez. He jokes about driving on the left side of the road after having become accustomed to the way they drive on the opposite side in Japan. But, he also recalls facing discrimination while traveling, along with fellow Latinos. It didn’t seem to matter sometimes that he’d served his country. For example, his skin color was enough to stop him from being served at a restaurant in Hughes, Ark., while traveling with some men in the Bracero Program.

"We didn't make a hassle about it," he said. "That's just the way it went."

In addition to facing discrimination upon his return, Ramirez felt he and his fellow soldiers had to catch up to the people who’d stayed behind. He and his fellow soldiers didn’t have jobs, and many hadn’t finished their education.

Ramirez followed in his father's footsteps and became a farmer and rancher. He recalls being paid $40 a month as part of the GI Bill to study agriculture upon his return.

In 1949, two years after being discharged from the military, he married Maria Zamora. They had 10 children. He’s very proud of having put his children through school. At one point, he had three jobs in order to finance their education.

Ramirez is proud of the fact that his children have gone on to become professionals such as principals, pharmacists, a banker and a mayor, among other occupations. You can see he and his wife’s pride in the way they have all their children's graduation pictures displayed on their living room wall.

Believing education is the key to a better life, he has tried to do his best to ensure his children don’t have to suffer through many of the harsh aspects of life that he did.

An education is the "best weapon" any person can have, Ramirez said.

Today, at the age of 72, Ramirez is retired. He and Maria live in Texas’ Rio Grande Valley in the tiny city of Peñitas, in the same home they’ve lived in for close to 50 years.

"I'm taking it very, very easy," he said.

In the evenings, he still goes to his ranch. He goes and relaxes while watching his cattle, then returns home to watch television and rest.

Mr. Ramirez was interviewed in Peñitas, Texas, on October 16, 1999, by Monica Jean Alaniz.