By Joanna Watson

Although Joel Hernandez enlisted in the Army only because he couldn't find a job, he looks back on his military service as a blessing that enabled him to lead a fulfilling life.

The son of Mexican Revolution veteran Candelario Castillo Hernandez and Manuela Mendez Ramirez, Hernandez was born July 27, 1917, in Mackay, Texas, the oldest of seven children.

Looking back, Hernandez says his family was poor, and everyone had to constantly work hard.

"We were farmers, and we had to work in the field," Hernandez said. "Work was the first priority. We went to school in the morning and then worked the rest of the day."

Although money was tight, the Hernandez family never struggled for sustenance, he says.

"We had plenty of food, but just no money," Hernandez said. "The only time we saw money was during the cotton crop."

Hernandez recalls his father would give his children 50 cents a week to use however they wanted.

"That was every week when we had money," he said.

Hernandez attended school through the seventh grade on the ranch where his father had settled. He recalls his dad taught his children to speak Spanish, although all of his classes were taught in English.

"Well, the teachers, they were all Mexican Americans, but they wanted us to speak English," Hernandez said. "They didn't like hearing us speak in Spanish."

Hernandez continued to work on his father's ranch when he met Rosela Black, a very well-to-do young school teacher from Katy, Texas. The two married in Laredo in 1936 and moved in with her parents on their ranch outside Katy. But Rosela died during the birth of their first daughter, Barbara Rosela, and Rosela's parents adopted Barbara.

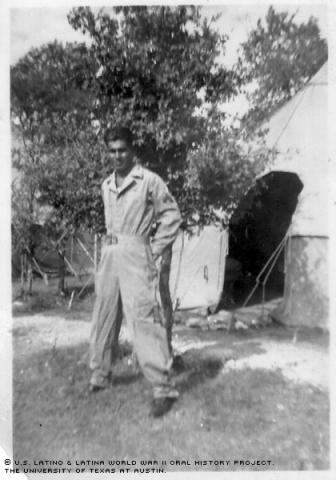

So on June 4, 1940, Hernandez decided to enlist in the Army.

"When Rosela died, I joined the Army," Hernandez said. "There just wasn't much work in Houston."

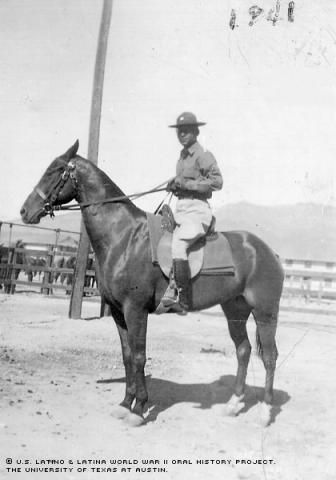

Hernandez attended basic training as a horseman in the 1st Cavalry Division at Fort Bliss in El Paso. He was in El Paso two years and it was there when war was declared.

He describes his time at Fort Bliss as very tough: He and another soldier were the only Mexican Americans and were given a hard time by the other soldiers, Hernandez says.

"The man that gave us the most problems eventually became a good friend of mine and then told the rest of the guys to not bother us," he said.

But soldiers weren't the only ones that gave Hernandez a hard time. Mexican American civilians called him a traitor because he was with the American Army.

"They wanted nothing to do with me," he added.

Hernandez says he was eventually transferred from the cavalry. He joined the 691st Tank Destroyer Battalion and moved to Camp Claiborne, La., where he eventually became a platoon commander of two tanks and had a crew of five men in each tank.

After Camp Claiborne, he trained at Camp Livingston, La., Camp Brownwood, Texas, and Camp Hood, Texas.

In 1944, Hernandez returned to Louisiana, where he was ordered to move to a deportation camp in Boston. The 691st had been assigned to the European Theater as an independent battalion and part of Gen. George S. Patton's 3rdArmy.

"We knew that if you got orders to go to Boston that you were going to Europe," he said.

Before they left for Boston, the soldiers were given a three-day pass. Hernandez and his friend decided to go to Houston and returned to Louisiana two days late. He was put under arrest for being AWOL and, as a result, lost his stripes. He never tried to earn them back.

The soldiers arrived in Liverpool, England, before eventually crossing the English Channel into France, where they landed on Utah Beach. Hernandez was part of the combat forces that followed the invasion of Europe through Luxembourg and Belgium and wound up in Germany in 1945 when the war ended.

He participated in the battle campaigns of northern France, the Ardennes, the Battle of the Bulge and the Rhineland, and said he "thanked God that I wasn't there during the invasion."

For his loyal and dedicated service, Hernandez was awarded the European Theatre of Operations Campaign Medal with four Bronze Stars, the World War II Victory Medal, the American Defense Service Medal, the American Theater Campaign Medal and the Good Conduct Medal.

In November of 1945, he moved back to a Houston that, like before the war, was starving for jobs. Hernandez noted in a letter after his interview that those who had trades were more likely to find work.

"When I came back, I didn't know what to do. There weren't a lot of jobs like there was during the war," he said. "All I learned in the Army was combat, and I couldn't find a job in that."

If the military didn't provide him with job skills, it did provide him with other skills that he was able to use and apply.

"I learned in the military service discipline and responsibility," he wrote. "Thank God for that -- it helped me in my life."

He became an automotive paint and body repairman, a trade he practiced for 36 years, until his retirement.

In addition to finding a trade, Hernandez began joining social clubs, where he met his current wife, Gloria Mayorga. The two married on Dec. 30, 1950, in Victoria, Texas, and have two children and five grandchildren. They credit the success of their marriage and family to their strong faith in God.

Gloria says her husband's time in the war had a profound impact on his life.

"It's taken me a lot of years to realize what he went through in the service," she said. "When we first got married, he was still reflecting on all of it.

"He's a great, great man, which I say in a lot of ways," Gloria said. "I am very happy."

Hernandez says he thinks people in the United States have become too fanatical over politics. And when asked for any advice for youngsters based on his life experiences, he jokingly replied, "You can't give them any advice, because they already know everything."

Mr. Hernandez was interviewed in Houston, Texas, on October 3, 2002, by Ernest Eguia.