By Hope Teel

Out of work with eight mouths to feed, Henry Rodriguez’s family left California in the early 1930s during the beginning of the Great Depression.

For Rodriguez, the family’s youngest member, the trip marked his first experience with racial discrimination.

“People didn’t know anything about backgrounds,” Rodriguez said. “People thought there were only Anglos and Indians, and we were Indians.”

As the family traveled across several states, Rodriguez watched his parents persevere, despite weather, racial and financial obstacles.

“We did not struggle in my viewpoint,” Rodriguez said. “We didn’t have much, but we didn’t go hungry because my family worked hard.”

Over the years, Rodriguez adopted his parents’ mentality as he learned to overcome his own hardships.

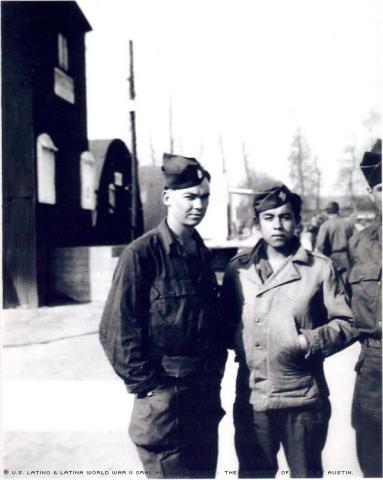

In March of 1944, Rodriguez became the third of four brothers to be drafted. One brother was in the 8th Air Force stationed in England, and the other was an artillery observer in France. Rodriguez remembers feeling like being drafted was normal.

“We knew it was our duty, so we went,” said Rodriguez, who was a private in the 99th Infantry Division’s 395th Battalion. They began basic training at Fort Hood in Texas, but due to an urgent need for more soldiers in Europe, the standard 17 weeks were cut to 12. His unit, a new one, was nicknamed the “Battle Babies.”

After a long trip across the Atlantic, Rodriguez arrived in Plymouth, England, in October of 1944. His unit spent three weeks in the barracks before transporting to Belgium.

Rodriguez recalls a nervous and exciting atmosphere. As the unit headed toward Belgium, its members began seeing flashes of light and hearing sounds from artillery shells in the distance. This was the “Battle Babies’” first exposure to actual fighting.

“That’s when we started to get scared,” said Rodriguez, who was a rifleman. “But you take it as it comes. What else can you do?”

Rodriguez turned 19 while sitting in a foxhole in the forested Ardennes region of Belgium. Ten days later, the Battle of the Bulge began.

“We got the offense of it, the artillery, rockets. I had never heard rockets before, 88s, machine guns, rifle fire, mortars, all at one time – at four in the morning …” Rodriguez said. “That was how it started.”

In the preface of “Nuts: The Battle of the Bulge,” authors Donald M. Goldstein, Katherine V. Dillon and J. Michael Wenger, describe the battle as “a patchwork quilt – a multitude of small engagements played out in or near small towns, most of no military significance.” Despite this fact, the U.S. suffered approximately 81,000 casualties, including 19,000 killed; The British suffered around 1,400 casualties, including approximately 200 killed. Germany lost an estimated total of 100,000 -- dead, wounded and captured. Image after image in Nuts is dominated by snow and rubble, complete destruction.

By the time he was fighting in the Battle of the Bulge, Rodriguez had seen countless dead bodies and had had several life-threatening experiences.

For example, he recalls having heard a light sound while walking back to his camp alone one day, prior to the Battle of the Bulge. As mortars hit the ground around him, he realized he’d been spotted by the enemy. Three mortars fell total, but Rodriguez wasn’t injured.

“I heard the first mortar shell breaking the wind with its blades, so I hit the ground,” Rodriguez said. “It was scary. It really shook me up.”

His division learned of the war’s end from German soldiers.

“They started coming out with their hands up. No rifles, no weapons,” Rodriguez said.

He described it as “a picture shot, like from a movie,” as they climbed into the hills to look into a valley at the Germans. The officers stood in front of their soldiers, who were lined up two miles behind them, as the officers led them into surrender.

Rodriguez had to wait six months before returning home. During that time, his unit was split up to move troops home faster, and Rodriguez was transferred into the 83rd Infantry Division. While in Rhineland, Germany, the Army gave him permission to stay with his brother, who was stationed in Munich.

“We ate good and took showers, which we never had before. It felt good. I felt very alive,” Rodriguez said.

On May 1, 1949, Rodriguez was discharged at Fort Bliss in Texas. His rank didn’t change, but he was awarded a Good Conduct medal, Distinguished Unit badge, Victory medal and an Army of Occupation medal.

Rodriguez returned to the Los Angeles area and began to look for a job, but for a Latino with an incomplete education, work was scarce. After his first job in the upholstery business with his brothers, he decided to go back to school.

Rodriguez began school in the first grade in the Orange Grove community on the Sespe Ranch, and was drafted four months before graduating. He knew the opportunity for school was still there, if he took the initiative. “Advantages are there, only if you take them,” Rodriguez said.

After trade school, Rodriguez had a few different jobs, at which he says he encountered racial discrimination.

“I didn’t let it hinder me,” Rodriguez said. “I wasn’t accepted for promotion, even though I was just as smart. But I went back to school, learned a lot and, in due time, things change.”

His sister, Mary Rodriguez, encouraged him to apply for a higher-paying job. Despite his skepticism, Rodriguez was hired, and ended up working at Lockheed on airplanes for 38 years. His starting salary was $1.10 per hour, a lot of money at the time.

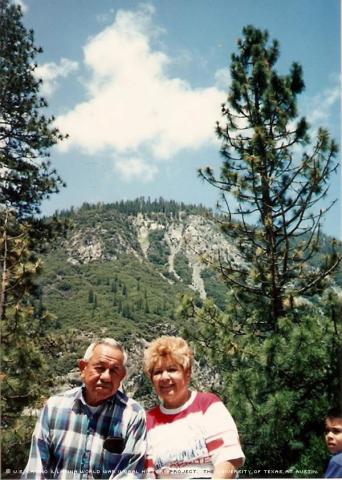

Rodriguez met his wife, Elvira [Rodriguez] Rodriguez, in 1951, and in 1956, they moved to California’s San Fernando Valley. The couple finally saved enough money to buy a new home, Rodriguez says, and chose San Fernando because they wanted a better place for their three children to grow up.

The Rodriguez family was the third family of Mexican-American background in the neighborhood, but he recalls no obstacles involving racial issues with his neighbors.

“We were inquisitive and patient. We learned from each other,” Rodriguez said.

He says he has seen many great improvements in relations between Latinos and Americans and that Latinos have wider possibilities than ever before.

“Accept what you can do,” Rodriguez said. “I took pride in everything I did. I never ran away from anything.”

Mr. Rodriguez was interviewed in San Fernando, California, on April 18, 2007, by his son, Ronald Galindo.