By Nikki Muñoz

The son of a laborer, Lupe Hernandez has been defined by the concept of hard work, having spent much of his childhood alongside his father in the fields.

Hernandez's parents, Guadalupe Hernandez and Isidora Garza Hernandez, moved to the border town of McAllen, Texas, from Mexico in 1918. After having immigrated to Texas, his mother was visiting relatives in Mexico and gave birth to Hernandez in Reynosa, Mexico, where his grandmother lived.

Hernandez has many memories of his childhood, but mostly he recalls working with his father in the fields.

"I was very close to my daddy. I was always his assistant," Hernandez recalled. "I wanted to help him, so sometimes I would miss school to work with him."

Although he learned the basics of English in class, he forgot them as soon as he got out of school because only Spanish was spoken in his home. He was able to achieve only an 8th-grade education before dropping out of school to help support his family.

Hernandez remembers making only 75 cents after working an entire day in the fields. With that money, his mother would send him to the store to buy a nickel's each worth of meat, bread and manteca, or lard, for the family, consisting of his parents, four brothers and two sisters. According to Hernandez, his neighborhood had four or five houses, with each family sharing a common outhouse and shower.

The Hernandez's house was small, with one bedroom, a small living room area and a kitchen.

"We would sleep on the floor, and there was an extra bed, so some of us would sleep on that," Hernandez said.

By the time Hernandez was 12, he got a job at a canning factory, where he worked for several years. One day he saw three men who’d joined the 12th Cavalry Regiment of the 1st Cavalry Division at Fort Brown near Brownsville, Texas. The trio clad in their uniforms, Hernandez was impressed.

So he hitchhiked to Brownsville to enlist in the U.S. Army and join them. And when he arrived, the doctor, a major, gave him a physical examination. He then told Hernandez he needed to go to town, eat a pound of bananas, drink plenty of water and come back because he was 1 pound too light. Hernandez decided against this, partly because his parents had no idea he’d gone to try to enlist. It turned out a blessing, because that division had seen hard battle abroad. The three uniformed men whose appearance had inspired Hernandez’s effort to join the war were among the casualties.

Hernandez said his primary motive in joining the military was to educate himself.

"War was the last thing on my mind. There was no sign of it. No one would have even thought about going to war at that time."

A short while after his failed attempt to join, the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor. Even though he was born in Mexico, he volunteered.

"You feel a sense of anger and that you have to help," he said.

Just as he’d tried to join the cavalry, he volunteered his services as a paratrooper. But again he was rejected, this time for being 1 inch too tall. Once again, he was saved from tragedy: Most of the men from that paratrooper division were killed in those early days of the war.

Then, on Nov. 10, 1942, Hernandez was drafted into the Army. He went through basic training at Camp Barkeley in Abilene, Texas, where he started the process of gaining American citizenship, he said in a letter after his interview. After basic training, he was sent to Camp Shelby in Hattiesburg, Miss.

The young soldier didn’t encounter any Latinos at either camp, and says he remembers being discriminated against, with the other soldiers taunting him.

"They would tell me to say things and laugh at me 'cause the way I pronounced them, but they bought me beer to keep me happy," Hernandez recalled.

Despite the difficulty of being the only Latino and not knowing the English language very well, he hoped to join the medical corps. He knew the needed skills, but his deficient English prevented him from joining. Instead, he was placed in the Medium Maintenance Division, which fixed vehicles and weapons carriers.

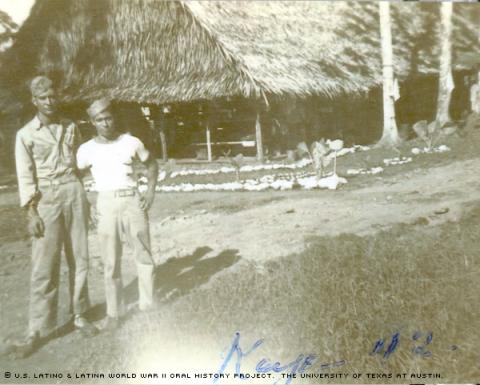

From Camp Shelby, Hernandez was sent to New Guinea, where he remembers being teased again for being Latino.

"It made me mad. One guy was reading a cartoon and asked me if Mexicans really live with chickens. Incidents like that happened a lot and it really aggravated me," he said.

In a combat zone for three months, Hernandez recalls groups of Japanese airplanes flying by, accompanied by loud warning sirens.

"We would hear those sirens and just start running to our places and it was scary," he said.

It was in New Guinea where Hernandez was finally made a United States citizen.

"And if you think Lupe Hernandez was the only one getting his citizenship that day, you are wrong," he wrote. "There were thousands ... Germans, Anglos ... from all over, all under a huge tent, like a circus."

The stress of war and the aggravation of discrimination within the ranks began to take its toll on Hernandez. Where once he hadn’t hesitated to volunteer for service, indifference set in. He constantly had his stripes taken away for misconduct, and told a superior he didn't care if he were court-martialed, as then he’d be able to escape the bad treatment he endured from his fellow soldiers. As his condition worsened, he was shipped off to a hospital in Van Nuys, Calif., where his nervous condition was ultimately documented as 100 percent service connected.

After being released from Van Nuys General Hospital, he was sent to William Beaumont General Hospital in El Paso, Texas, then on to Brooke Army Convalescent Hospital in San Antonio. Shortly after, he was honorably discharged at the rank of Private. Upon his discharge, he was handed his citizenship papers; the Army had ensured his naturalized status while he was in the service, so he returned to Texas’ Rio Grande Valley a newly minted American.

Hernandez began working at Roper's appliance shop as a technician. He was able to use the knowledge he gained there to open up his own repair shop, which he ran for a few years. He took subsequent technician-related jobs at a hotel and a Baptist church before retiring.

The skills he learned in the Army made up for his lack of formal education, Hernandez said. To this day, he stresses to young people the importance of an education.

"Be prepared to go out there and meet your future with a good education -- that is the best thing you could do."

These days, Hernandez and his wife, Emma Villareal Hernandez, who also served during WWII as a secretary in the Navy, enjoy their retirement together. He continues to be active in military-related activities, including membership in the Honor Guard, which performs ceremonial military honors at veterans' funerals. Although poor blood circulation in his leg sometimes keeps him from participating, he attends as often as he can.

"We are the only Honor Guard in this area and we are very proud to do it," said Hernandez, before reflecting on his tour of duty. "I regretted being in the military at the time because of the treatment I got. But everything I know, I owe to the service."

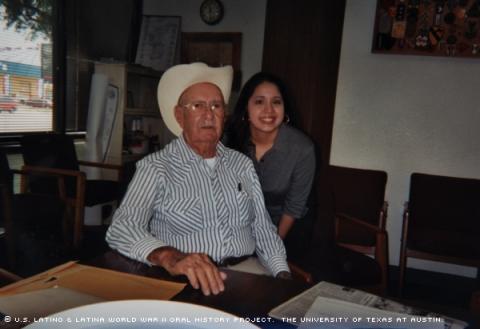

Mr. Hernandez was interviewed in McAllen, Texas, on April 6, 2002, by Nicole Muñoz.