By Ashley Mastervich

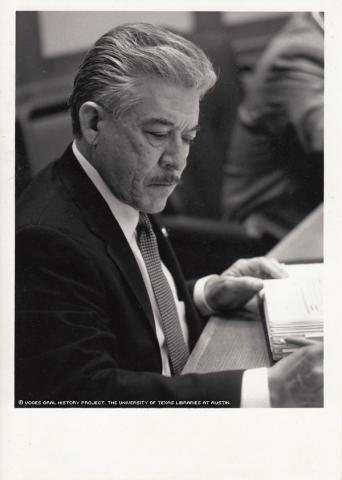

As one of the first Mexican Americans to represent Travis County in the Texas House of Representatives and Senate, Gonzalo Barrientos Jr. was part of the first wave of Latino officials who led the way for minority groups in local, state and national politics. Following the lead of his early role models, men like John F. Kennedy and Lyndon B. Johnson, Barrientos devoted his career as public official to challenging the inequalities he witnessed and endured in his youth.

Growing up, Barrientos recognized that the power was in the hands of Anglos, what he called "the good ol' boy system."

"You have to live it to really know what it is about. And it is about being treated unequally. It is about not getting promotions in your work. It is about training someone else for the job you have, then getting demoted," he said. "Walk in my shoes, and see what it's all about."

Barrientos' knowledge of Mexican-American civil rights began during his childhood in Bastrop, Texas.

On June 15, 1948, a Mexican-American attorney from San Antonio, Gustavo C. "Gus" Garcia, filed suit against Bastrop Independent School District and three other school districts. Garcia, along with Bob Eckhardt and several other attorneys, represented a young girl, Minerva Delgado, along with the parents of 20 other Mexican Americans who were required to attend segregated schools. Garcia argued that excluding Mexican Americans from Anglo schools was unlawful.

In September 1949, Judge Ben H. Rice of the U.S. District Court, Western District of Texas, said the segregation was unconstitutional. Even though the lawsuit began the process of desegregation for Mexican Americans, the court still permitted separate classes for non-English-speaking first-graders.

CHILDHOOD

Barrientos was born July 20, 1941, in Galveston, Texas. His family had moved there from just outside of Bastrop, about 35 miles southeast of Austin.

Before that, his father, Gonzalo Barrientos, Sr., had worked as a miner in the soft coal mines northwest of Bastrop. However, the unprofitable mines closed down in the late 1930s, causing the Barrientos family to relocate.

In Galveston, Barrientos Sr. married Christina Mendiola, another native of Bastrop. He was a longshoreman, unloading and loading ships. But in 1941, he hurt his back on the job and couldn't continue working. Barrientos Sr. relocated his family back to a Bastrop farm that same year, shortly after the birth of Gonzalo Jr. Another child, Alicia, was born to the family in 1944.

Barrientos spent his childhood on the Bastrop farm and was part of the migrant farmworker force that traveled to fields in Central, South and West Texas.

Back then, discrimination against minorities was commonplace. For example, Mexican Americans were not allowed to eat inside most restaurants.

"I think we invented fast food because we couldn't eat in the cafes or restaurants. We would order around the back door: fast food to-go," Barrientos said, snapping his fingers for emphasis.

"Before desegregation, there were three schools in Bastrop - one for blacks, one for whites and one for Mexicans," he said. "Fortunately, I only experienced one year of segregation.

"At the time I was 6, I would go to school and teachers would give us a sheet of paper, a blank sheet of paper, and a crayon. 'Knock yourself out!' And that was it," he said.

Despite these memories, Barrientos said his lifestyle was not always typical of Mexican Americans living in Texas. Barrientos said that segregation was uneven within the state.

One day, he came home crying after school. His grandfather, Jesus Barrientos, asked him what was wrong.

"'The white kids don't like me.' My grandfather replied, 'Do not blame them; blame the corral in which they grew up,'" Barrientos said, saying it in Spanish, then switching to English.

Even though Barrientos talked about these "interesting memories" of desegregation, he said he was thankful that the Delgado lawsuit gave Mexican Americans more opportunities for an education.

"I can only tell you that I probably would not have gone further than two or three grades in school. Like most other Hispanics, [I would have] gone out as a teenager to work and help the family, be it picking cotton or driving a truck or what have you," Barrientos said. "I would like to think I would be on my own reading all kinds of books and becoming a learned leader, but the odds would be against us in that kind of situation.

"That's why I think we ought to honor the civil rights lawyer, Gustavo Garcia from San Antonio, and several other people who helped him, including Bob Eckhardt," he said. "I think that those individuals, those leaders, didn't realize the full impact of their work. ... It affected millions of children."

Barrientos earned his diploma from Bastrop High School. He was an active student. He played trumpet in the school's band, and lettered in football, baseball and track.

He said John F. Kennedy and Lyndon B. Johnson were his role models in his teenage years. Barrientos paused to regain his composure while discussing Kennedy and Kennedy's idea of serving his country.

"When you heard John Kennedy speeches, and talking about equality and justice - it was almost religious about doing for your brothers and sisters across the board. ... He made you feel like you were part of this country," he said.

Like Kennedy and 68 percent of the U.S. Hispanic population, Barrientos is Catholic.

"Like in a lot of Hispanic, Mexican-American homes, you might have an altar in the corner of a room. You have Jesus Christ on the cross and a couple of saints. My mom had a picture of John Kennedy on this altar too," Barrientos said. "It's kind of emotional because the anniversary [of Kennedy's assassination] is coming up."

Barrientos also spoke proudly about shaking hands with Johnson. In 1959, his high school band was asked to play during a rally at the American Legion for Johnson, then the majority leader of the U.S. Senate.

"So, the band - we were out there in our uniforms sitting to the side and there was an outside pavilion. At some point, we were told we were going to start playing 'Happy Days Are Here Again.' All the people start marching around that outside pavilion with signs...'LBJ all the way!' And I thought we would never stop playing 'Happy Days Are Here Again.' We had to play it about 15 or 20 times," he said. "Afterwards, the band got in a single line and all of us went by and shook hands with LBJ. He's a tall dude!"

YOUNG ADULTHOOD

Barrientos met his wife, Emma Serrato, shortly after high school. They were married when Serrato was 17, and Barrientos was barely 18.

"We kind of grew up together," Barrientos said with a chuckle.

The couple moved to Austin so Barrientos could begin his college education at the University of Texas at Austin.

"I originally wanted to major in hotel or restaurant management. But then I thought out of all the things I, my family, and other Tejanos went through," he said. "I wanted to do something more useful. I decided to study subjects such as sociology and psychology."

By his junior year of college, the Barrientoses had three children. Barrientos juggled his studies with working to support his family. One of his jobs during that time was as a ward attendant for the State of Texas Department of Mental Health's residential facility.

"I realized it [mental underdevelopment] affected anyone no matter what color you were. They [the patients] were like children in men's bodies," he said. But he also noticed that some of the boys had been placed at the facility without an evident problem.

"Some of the kids there did not belong there. Interestingly, they were Mexican-American kids. I think they had problems at home or with the law," he said. "But they sure as heck didn't belong in that institution."

Barrientos also described one memory that taught him a difficult lesson about life and death.

"I had a kid die in my arms," he said. "There was a white kid who - I don't know - must have been at least 18 or 20 years old. We had these metal benches out there ... and that one man, like some of the other developmentally challenged kids, walked on his tiptoes all the time. There is a term for that too. But he fell and hit his head on the corner one of the benches right here," Barrientos said, smacking the corner of his desk for emphasis.

"He fell, and I went to grab him. He started having seizures. So the thing I had learned was to take my comb and wrap my handkerchief around it, and put it in his teeth to not bite himself," he said. "But he died. That was tough."

THE ENACTMENT OF THE VOTING RIGHTS ACT

Barrientos left the University of Texas without receiving a degree around the time that President Lyndon B. Johnson signed the Voting Rights Act into law in 1965.

Barrientos said the Voting Rights Act demonstrated that all Americans were equal. But there was widespread misunderstanding about the act and its implications for the underrepresented, he said. Many Americans did not quite understand why the legislation came about, he said. Some who studied the law understood it, but many white Southerners did not want to understand it, Barrientos said.

He also mentioned Johnson when discussing a statement made by the president about the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

"As Lyndon Johnson said, 'We [the Democratic Party] lost the South for a generation because of that,'" he said.

PROFESSIONAL EXPERIENCE

After leaving the University of Texas, Barrientos advocated for Mexican Americans through his work. He worked as a community organizer for the National Urban League and as a program officer and trainer for Volunteers in Service to America, a domestic service program that is now part of AmeriCorps.

Throughout his work in the government sector and later, in his political career, Barrientos aligned himself with the Democratic Party.

"The Democratic Party has been there, for the most people, on the most issues. You have your Social Security, Medicare, GI Bill ... all those issues have been for the general public and the less fortunate," he said. He adds to this list the civil rights laws passed under Democratic leadership.

"I am liberal sometimes. I am conservative sometimes. I am conservative about spending money, especially other people's money. I am liberal when it comes to helping people and making darn sure that women's rights are fully supported, and that voting rights are supported, and education is equally supported for everyone. If you want to call that liberal, then go ahead," he said. "I call it common sense."

Barrientos' career aspirations were changed one evening at the Salvation Army hall in Austin, where a group of Hispanic leaders was meeting.

"Several activists in the community and myself were talking about the problems the community had," he said. The men in the room knew the issues could be solved through legislation.

Barrientos mimicked how the men pointed around the room to see who would run for the state Legislature.

"We went around," he said. "And somebody would say, 'Oh, I don't speak well.' How about you? 'I have too many children.' How about you? 'I work at night.' And finally I said, 'Well, I'll do it.'"

POLITICAL CAREER

In 1972, Barrientos ran against an incumbent, Wilson Foreman, for Texas State House District 37. Barrientos lost in a runoff, but he came back two years later to challenge Foreman and won by 94 votes in another runoff.

"The first time it was the Heartbreak Kid. The second [time] it was a landslide: Barrientos by 94 votes. We learned a lot from '72 to '74," he said. "For example, phraseology in statements, what people were or were not interested in, what the issues were, listening directly to the people.

"At the same time, we [the campaign] went to a political consultant who was just getting started, Peck Young," he said. He also found a media consultant, Dean Rindy and Associates.

"We became very polished very quickly in the methodology," he said.

Barrientos spent 10 years in the Texas House. He won election to the state Senate in 1985, representing District 14. Barrientos continued to advance the rights of all underrepresented citizens. And he learned as he went.

"At first one thinks, at least I, that you go up to the front microphone and give a heck of a speech and pass along [legislation]," he said. "It didn't work like that at all. There are committees. There are rules. You have to get along on each of those steps. It is very difficult to pass a law. It is very easy to destroy and crash with what you are trying to carry.

"You go into the House and the Senate, or at least the House. You want to do everything. You want to introduce 55 bills, you want to work on this, on this, on this. But I learned, if you are really serious on passing legislation, you prioritize," he said. "You take three or four bills, and you work your heart out on those."

Among the bills he is proudest of is HB 588, which gives the top 10 percent of Texas high school graduates automatic admission to any public state university.

"The Senate was more of a 'gentlemen and gentle ladies' area of legislative process. But there were still some fights in the Senate," he said.

These "fights" could be seen in two filibusters he staged while serving in the Texas Senate. Filibusters put pressure on the Senate to get something accomplished by blocking legislation, he said. This tactic also allows senators to extensively discuss pending legislation, which prevents the matter from being voted on. The first one took place in 1993 and concerned a creek that feeds Barton Springs, a popular swimming hole in Austin.

"Legislation was pending that would harm Barton Spring and the Edwards Aquifer. In one case, for 18 hours I filibustered," Barrientos said. "In the other case, for 21 hours I filibustered and killed a few of their bills and made them realize they must protect the environment."

Filibusters are physically exhausting, he said.

"You got to stand there. You can't lean on your desk, you can't sit, you can't eat, and of course you can't go to the bathroom," he said. "You have to talk continuously and stay on the subject. And after about 10 hours of that, you start to get a little tired and woozy."

Barrientos also admitted feeling frustrated throughout his political career.

"You do get quite frustrated sometimes, especially in the later years when more Republicans were being elected and they were putting down your priorities as low priorities," he said. "You have to remember you are not up there for your own glorification. You are there because you are representing people in your district and the people of Texas. You just keep going."

State legislators in Texas are paid only $600 a month, and that made it difficult to support his family and still do his job well.

"After being there [in the Senate] for 21 years, it was always kind of a struggle. If you're wealthy, have a big business, or an attorney, you can do that on the side. Otherwise, the other members have to work and do that at the same time," he said.

Having a full-time outside job was difficult, he said.

"Because I was from Austin, I was on-call all the time," Barrientos said. Unlike representatives from other districts, who go back to their hometowns when the Legislature is not in session, Barrientos stays in the capital.

Barrientos described an occasion in 2003 when he went to Albuquerque, N.M., for six weeks with 10 other Senate Democrats to block the Republicans from passing redistricting legislation. The event followed a similar action by a group of State House members who had traveled to Oklahoma for several days to block a redistricting plan earlier that summer.

"The only avenue we had left to fight against it was to break the quorum," he said.

Barrientos said there is still work to be done to advance the rights of Mexican Americans.

"Unfortunately, I don't think enough young people realize some of the trials and tribulations that certain people in our country went through," he said. "For example ... many people today would look at me, or someone of a little color and with the name Gonzalo Barrientos and think, 'Huh, you just walked across the border, didn't you?' That's not the case.

"There's so much to learn, and I don't think enough of our students, especially our Hispanic students, know the background, where we come from, who we are and where are we going," he said. "A lot of the history is not being taught in our public schools. And we seem to be walking backwards in a way, if you look at the Texas Senate."

The state is undergoing a transition, demographically. If Mexican Americans began voting in large numbers, there would be a major shift in political power, he said. "I think ... the right-wing Anglo... is afraid of that."

"No -- they [Hispanics] are not going to do the same darn, silly, bigoted things that were cast upon us in the past," he said. "We want to be true Americans. That's all."

Mr. Barrientos was interviewed by Ashley Mastervich in Austin, Texas, on Oct. 9, 2013.