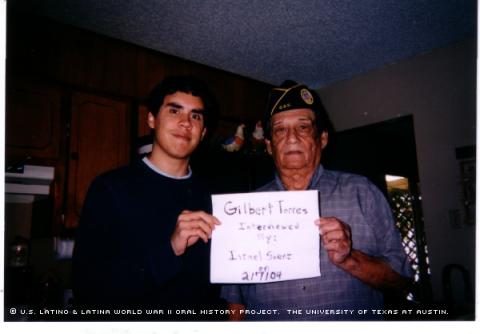

By Israel Saenz

A long, jagged scar marks Gilberto Roque Torres' right forearm, a permanent reminder of a summer day in France that would be his last in combat. Torres doesn't remember too many dates of events that occurred during his military service, but a glance at the 60-year-old scar can bring August 7, 1944, back to him as if it were a day last week.

That day marked the end of his World War II service in war-torn France – specifically, Brittany -- and the beginning of his return to the quiet life of rural Central Texas.

Torres was born Sept. 1, 1925, in Brady, the self-proclaimed "Heart of Texas." His father, Lazaro Bermudes Torres, moved up to Brady from Brownsville, Texas, to find work as a farmhand. His mother, Lorenza Roque Torres, migrated with her parents and brothers from Coahuilla, Mexico, to Brady, where she and Lazaro met, married and eventually had nine children, of which Gilberto was number six.

Torres says he and his large family never suffered, as they were sharecroppers who did work on other people’s land for a portion of what was grown. For young Gilberto, life consisted of going to school and getting to work right afterward.

"As soon as we got home, we had to go down to the fields," said Torres, who attended a segregated elementary school in nearby Melvin and quit going to school after the fifth grade. It was enough to learn passable English, as his parents spoke only Spanish.

The simplicity of life on the farm was interrupted one day in December of 1941, when news that would forever change his life came running toward 15-year-old Torres through the fields in the form of the property owner.

"We were out near Brownfield [,Texas], picking cotton," Torres said. "The owner went out there; he was running like the dickens."

That day, Torres found out Pearl Harbor had been bombed, but it would be several years before he was able to serve.

"I was drafted, but I wanted to go," Torres said. "Anyway, they got me."

After induction in October of 1943, Torres went through six months of basic training at Camp Fannin in Tyler, Texas, and from there was sent to Fort Meade in Baltimore, Md. After embarking for England from Camp Kilmer in New Jersey, Torres received further infantry and artillery training in Southampton, Great Britain.

"They trained us good," Torres said. "They needed a lot of soldiers out there, [and] they needed us pretty quick."

He and other U.S. soldiers were being prepared to reinforce the first waves of invasion into Normandy. On June 19, 1944, Torres set foot on the beach, and the horrors of battle greeted him upon his arrival.

"Soon as you hit the beaches, all you see is dead soldiers floating in the water, all around you," said Torres, who soon began to develop a jaded attitude toward his gruesome and violent surroundings. "You dig into the beach, and you go in to the front," he said. "To tell you the truth, after awhile you just don't give a damn."

Torres joined up with the 83rd Infantry Division, also known as the Ohio Group, which had received orders to capture the port town of St. Malo. Due to its turbulent history and position on the northeast coast of France, the town was surrounded by a brick wall and defended by about 12,000 German troops. A German colonel named Andreas von Aulock, who vowed to fight to the very last man, led them, Torres recalls.

Headed toward their destination, Torres and the other American troops were confronted by the carnage left behind from earlier fighting.

"Nothing was beautiful in France," he said. "The whole place was a mess."

One day, while marching through a village, a French woman and several children approached Torres and other troops.

"This lady and these kids went up to us, and offered us something to eat," Torres said. "They [his superiors] told us not to accept the food, because it could be poisoned. I started to cry. We were hungry."

The 83rd Division trudged through rivers, ponds, swamps and minefields. As they approached St. Malo, mortar and artillery fire, some from the nearby Isle de Cezembre, out in the bay, rained upon them. After entering the city, it would take two weeks of house-to-house and street fighting to force a surrender from the once-defiant von Aulock.

Torres wouldn't be there to celebrate the victory with his comrades, however.

On Aug. 7, while still outside the city, he and other American troops came under enemy machine-gun fire. Torres was hit in the right forearm; the slugs also grazed the right side of his upper torso.

"They used to call it a burp gun," said Torres, of the submachine gun used to wound him. "They [the enemy] were at the edge of a hedgerow, and we were just walking across a field."

Forty-eight days after landing on the beaches of France, Torres' fighting days were over, and he was flown to a hospital in Liverpool, England.

The other wounded men he saw along the way made him realize he didn't have it too bad.

"I saw one of them with no arms or legs," Torres said. "Just a torso."

After a lengthy recovery in hospitals in England; Charleston, S.C.; and El Paso, Texas, Torres was back home. He was discharged March 1, 1947, as a corporal, and was awarded the Purple Heart, a Bronze Star Medal, American Campaign Medal, Combat Infantry Badge, Good Conduct Medal, Honorable Service Lapel and European-African-Middle Eastern Campaign Medal.

Torres married Olivia Reyna in 1949, and they had three children. After they divorced in 1960, he married Rosa Valencia in 1971, and had three more children.

Back home, he did farm work until getting a job fixing used cars at Meier Motors Co. in San Angelo, Texas, for 17 years. He retired in 1969.

He says he’s grateful his children had better opportunities than he had when he was younger.

"They got a better education," said Torres, who has two children -- Guillermo and Sandra -- who earned a journalism fellowship and a bachelor's, respectively. "The education system [is] a lot better than it used to be."

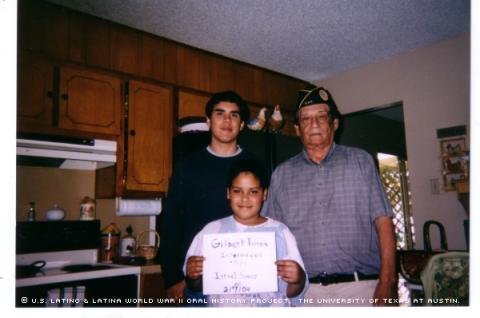

Approaching 80, Torres enjoys doing occasional landscaping work to help him keep in shape, as well as spending time with his grandchildren. He says he has never regretted fighting for the American cause in WWII, adding that he realizes it was one of his few options. Torres became one of the first members of the G.I. Forum, aiding in the fight for equal rights for Mexican Americans. He has encouraged his grandchildren to take advantage of the opportunities that were lacking during his youth.

After looking down at his scar, made by that German burp gun in early August of 1944, Torres looks to his 10-year-old grandson, Derrick, and asks him:

"You're gonna go to college, right mi'jo?"

Mr. Torres was interviewed in San Angelo, Texas, on February 7, 2004, by Israel Saenz.