By Ximena Mejorado

Cal State, Fullerton

When he got his draft notice at the age of 18, Germán Abadía’s first thought was to go into hiding.

The Puerto Rican native said he did not understand why he needed to go to Vietnam to fight a war, which he knew nothing about. His mother, Gilia Olmeda, changed his mind. If he was called to the Army, he had to go or he would be jailed, he recalled her telling him.

Abadía, who was born on Sept. 3, 1948, was raised by his uncle and aunt, Juan and Modesta Abadía, whom he called his parents. Abadía’s biological father, Domingo Abadía, left his mother and moved to New York, never looking back. Hoping to get back together with Domingo, Abadía’s mother left Puerto Rico and went to New York as well, leaving all her children behind.

Germán Abadía never forgot the first time he saw Juan Abadía cry. It was the day he told him he was being drafted into the Army. The younger Abadía fought back tears as he remembered the scene. He always thought of his father a tough, strong man, so seeing him cry was difficult to witness. His dad told him to go serve his time but that he had to come back.

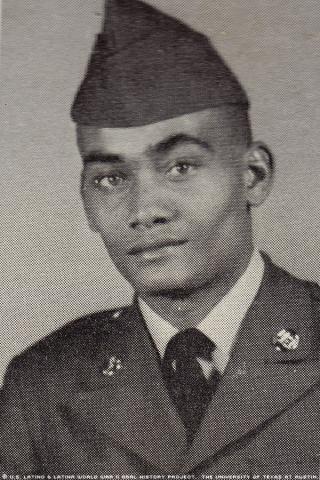

He was scheduled to report by Jan. 1, 1967. Abadía recalled being at Isla Verde International Airport in San Juan, P.R., and seeing all the other men who also had been drafted, as he boarded a huge Trans World Airlines airplane.

He was sent to Fort Jackson, S.C. for basic training. His first impression of Fort Jackson was that it was very cold. But his toughest challenge was the language barrier. Abadía spoke mostly Spanish as a young man and the little English he learned in school was not enough. So, at boot camp, Abadía said he would get upset because sometimes Army trainers would repeat “¿No comprende?” over and over again when he did not entirely understand what they were saying. To him, it felt like it was said out of malice.

Abadía said he was lucky enough to know one of the corporals, who assured him that he would not have any problems as long as he just did as he was told.

The training was easy for him because he was physically fit. The military discipline he encountered was also easy because he was taught to be quite organized growing up. While outdoors, soldiers were required to be running, and when they were indoors, they had to be “walking strong,” meaning taking heavy steps. If a soldier were caught walking outdoors, he said, the sergeants would make him drop and do push-ups.

After two months of basic training, he and six other Puerto Ricans were transferred to Fort Benning, Ga., for Advanced Individual Training. He recalled that they went by Greyhound bus.

Abadía said the sergeants there asked him to consider airborne training, since he was so fit and strong and was always running. Abadía said he accepted the challenge and completed the training with flying colors.

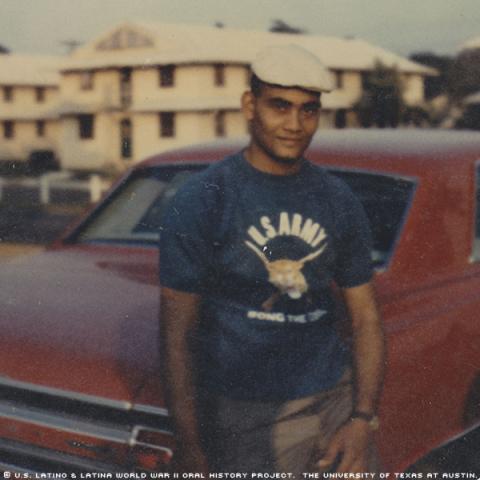

After about a year, he completed his airborne training and was given 30 days to go back home before being sent to Vietnam.

Abadía was supposed to report back on Dec. 31, but he did not show up until Jan. 8, two days after the Three Kings Day festivities that traditionally end the holiday season on the island. When asked why he did not return when he was supposed to, Abadía responded by saying that Christmas in Puerto Rico was too good and going to Vietnam could mean that he might never get back home to Puerto Rico. Abadía’s punishment was to work three months with no pay.

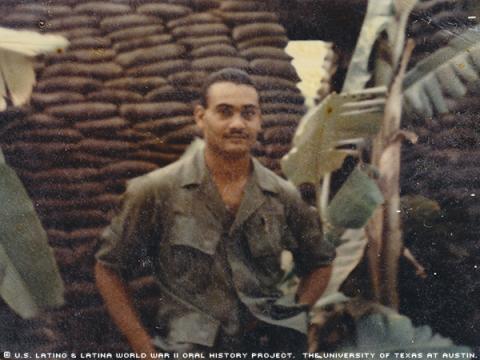

In Vietnam, Abadía said, he arrived at the replacement center, which was swarming with newly-arrived soldiers waiting for assignment. He would eventually serve in the 159th Engineer Group, 46th Engineer Battalion (Construction), Company A.

The first thing he noticed about Vietnam was the scorching heat. Soldiers would cut off their sleeves to keep cool and carried a rifle over their shoulder at all times. Since the weather was similar to that of Puerto Rico, Abadía adjusted easily.

Abadía remembered that his first operation was to perform guard duty with two other soldiers. While one of the soldiers slept, the other two had to be on watch and every two hours they would rotate. Abadía remembered that, when it was his turn to sleep, he woke up and realized that the other two soldiers were sound asleep. He said he yelled and asked why they were asleep only to realize that both soldiers had gotten high on marijuana. As a result he remained awake the rest of that night.

The food they had in Vietnam was typical American food. They had personal cooks to prepare their meals. Vietnamese women did the cleaning at the base. Soldiers had money taken from their paycheck every month for that service. Some soldiers hired a Vietnamese woman to only be in charge of cleaning their personal space and clothes.

Abadía recalled building a great friendship with Trang, the Vietnamese woman he hired to work for him and clean. He would even ask his mother to send her clothes in his care packages.

Even for someone who was used to tropical weather, the rain in Vietnam really stood out for Abadía. One time during a military operation, it did not stop raining for five days straight. Not only was the rain horrible, but there were insects everywhere, snakes in the jungles, and crocodile-like animals lurking everywhere. Soldiers would protect themselves with ponchos on top of their uniforms. The only thing they were able to change was their socks during those long operations when it rained continuously. Many would get sick, he said, recalling that one soldier contracted malaria. Abadía said he suffered from a foot infection during one operation.

A constant separation of whites from the rest in the military was another thing Abadía said that he noticed during his Army tour. He remembered experiencing racism throughout his service. It didn’t help that geography many people had never heard of his Caribbean homeland. Once people asked him where he was from, they would always follow by asking where Puerto Rico was. They often said that they had never heard of it.

During his free time, Abadía would read his Bible. He said that he believed his faith helped him get through the tough times in war.

Abadía said that, if given the choice to go through war again, he would not go. He also would never wish that upon his children. Abadía said he always expressed his negative feelings about war to his children. He said he believed wars are strictly political, so why should he have had to risk his life fighting Vietnamese people, who never did anything to him in the first place?

Vietnam was a crazy war, Abadía recalled. He said two months of basic training was not enough and simulation exercises were completely different to real-life combat. He said most of the soldiers were so young that they were often homesick and suffered panic attacks.

Another reason Abadía said Vietnam was a crazy war was because many Vietnamese had permits to work on the military base. He felt that the Army was working with the enemy. Sometimes, the day after attacks, they would be shocked to find the dead bodies of the Vietnamese men they had worked with. He said it was an inner struggle they had to deal with, working with these Vietnamese while wondering, in the back of their mind, if they were good or bad.

Perhaps he could have done more with his life if he had a good job before being forced to join the Army, Abadía said. He believed that his health also suffered because of the war and exposure to the Agent Orange herbicide that U.S. military used to clear parts of the jungles in which North Vietnamese fighters hid. He had diabetes and high blood pressure.

Abadía said he also suffered from post-traumatic stress disorder. His mother would have to wake him up two or three times a night because he would be kicking and screaming, yelling in English things like: “Watch out!” He suffered from these nightmares for many years. And every time he would hear a loud noise, no matter where he was, he automatically would drop on the ground and take cover, he said.

When asked if there was anything good that came out of his military experience, Abadía said he made the transition from a boy to a man.

During his service, Abadía earned a National Defense Service Medal, a Vietnam Service Medal, a Vietnam Campaign Medal and a Good Conduct Medal.

(Mr. Abadía was interviewed on June 17, 2010, in Fajardo, P.R., by Manuel Avilés-Santiago.)