By Borger Bargas

On April 29, 1945, Genovevo Bargas and some of his shipmates looked to the sky from the deck of the USS Comfort. A Japanese kamikaze was headed straight for their hospital ship. They were in the midst of the Battle of Okinawa, the last major battle of World War II.

The kamikaze missed the USS Comfort’s smoke stack, but still managed to create a huge hole in the vessel.

“We only saw one part of the Japanese [pilot’s] body,” said Bargas, motioning from the neck up, “the rest was nothing.”

He admits he was lucky to survive one of the most devastating Japanese attacks of the war – one in which Japanese soldiers were willing to die for their country while American soldiers were fighting to live for their country. By crashing a plane into this hospital ship, the Japanese killed 28 Americans and wounded 48.

“We lost a lot of people, but I don’t remember how many. That was the worst of my close calls,” Bargas said.

Today, he still feels a pinching sensation on his back from being thrown to the deck after the plane hit. He never reported his injury, but his chronic pain remains a memento of war.

During WWII, Bargas served in the Navy as a supply clerk with the 205th Hospital Ship Complement. He traveled throughout the Pacific Theater, picking up wounded soldiers to care for them aboard the Navy’s hospital ships.

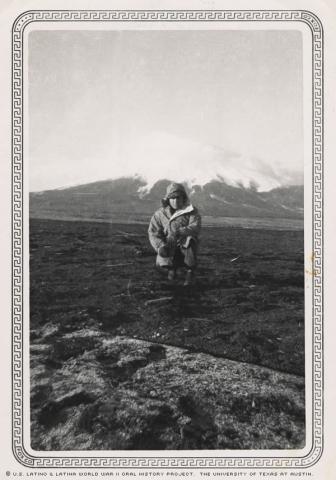

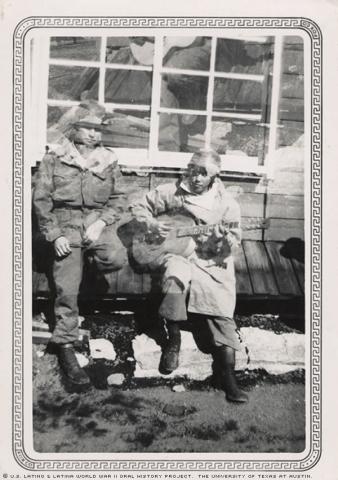

On May 11, 1943, while serving on another ship, he approached the Aleutian Islands. This ship hit an underwater reef and sunk. The crew evacuated to the shore and into the combat zone.

Once ashore, “[A member of the infantry] threw a gun at me. I said, ‘I’m a medic,’” recalled Bargas, to which the soldier replied, “No! Right now you belong to the 17th Infantry,” and Bargas’ wish to be part of the action finally came true.

Bargas doesn’t like to talk about the Asiatic Pacific Theater Ribbon and the six Bronze Stars he earned during his stay at Attu. He insists his wife, Lupe Guevara Bargas, is the only other person to whom he ever described his tales of narrow escapes and near misses from serving in the war.

Bargas only shared snippets of the danger he and his fellow servicemen faced. For example, while in his pup tent in the Aleutians, the Japanese raided his camp, stabbing their bayonets into each tent.

“I could almost feel a bayonet, but they missed me,” he said, “If he had got me with that bayonet, I wouldn’t be here.”

Born July 16, 1922, in Victoria, Texas, a town about 30 miles inland from the Gulf of Mexico, Bargas was the second of Louis and Martina Bargas’ five children. His mother was a homemaker. His father did yard work to support the family. Both parents believed it more important that their children work than graduate from high school.

“I was very disappointed,” said Bargas about his father’s choice to take him out of school to begin working full time after the eighth grade. “It breaks your heart to not be able to care about college.”

Prior to the outbreak of WWII, Bargas joined the Civilian Conservation Corps, a government agency founded by President Franklin Roosevelt to employ out-of-work men during the Depression.

“I was still in the CCC camps when Pearl Harbor was bombed in 1941,” Bargas said.

When President Roosevelt declared war, Bargas says he decided to enlist. He tired to join the Marines but was rejected because he had a broken arm.

Then, on Nov. 13, 1942, he was drafted.

Bargas’ first stint in the military ended Dec. 21, 1945, but he reenlisted in 1948 so he could make a career. The Army needed soldiers who already had gone overseas so they could help train the new recruits.

“I stayed until just before the Korean War,” Bargas said. “I know if I had gone I probably wouldn’t have made it home, and my mother needed me.”

The Army honorably discharged him Dec. 19, 1945, at the rank of Private First Class, and the Red Cross provided him with money to aid his ailing mother.

In June of 1950 he came to San Antonio, Texas, where his mother lived. There, he found work as a barber. He met the woman who’d be his wife at the bus stop where he waited each day.

Lupe Guevara was very shy because she didn’t know much English, Bargas says. One day he spoke to her in Spanish and she replied, “Oh, I thought you were a ‘gringo’!”

They married in 1953, the year the war in Korea officially ended, and eventually had three children, all of whom Bargas encouraged to graduate from high school and go to college. Even though he learned a lot from his service – “good and bad, and good from bad,” along with the importance of hard work – he knows now that an education is invaluable.

“If you have children, see that they get a good education so they can be good for the community,” Bargas said. “We support education and we want our kids to do the same.”

Mr. Bargas was interviewed in San Antonio, Texas, on August 4, 2007, by Raquel C. Garza.