By Sarah Jackson

Drafted at 21, Frank Cordero endured hardships typical of most soldiers. But in telling his story, he prefers to dwell on the lighter side of war.

Born in 1921 in Alamogordo, N.M., Cordero was the youngest of five children born to Felix Cordero and Benjardina Gonzales Cordero. He joined the U.S. Army in 1942 and was sent to Fort Bliss in El Paso, Texas, before being shipped out to Camp Gruber near Muskogee, Okla., for basic training. The "final exam" of the yearlong training was three months of maneuvers in the Louisiana swamps.

During these operations, the troops received food twice daily; in the morning, they were given breakfast and lunch, with dinner coming in the evening. This unusual meal schedule provided a moment of needed levity during Cordero's wartime stint.

Having missed the morning chow call one day during basic training, he and other squad members who’d overslept decided to find food for themselves.

They left camp searching for food and came across a farm at the edge of a swamp. The hungry soldiers knew it was forbidden to leave the camp, but were emboldened by their rumbling stomachs.

Cordero approached the farmhouse, only to encounter a group of excitable dogs in the yard of the home. Emerging with a few scratches, Cordero knocked on the door, explaining his plight to the woman who answered. Smiling, she assured him she always cooked extra food during maneuvers. After sating his appetite, he carried sandwiches back to his squad.

Cordero also remembered his introduction to the art of dice while in Louisiana. His first few games as a rookie gambler went well, yielding $600 when the game broke up in the early hours of the morning. However, there was one slight problem: There was no place to spend his winnings in the swamp, and he was nervous carrying such a large amount around with him until the maneuvers were over.

Cordero decided to send the money to his wife in Los Angeles and set out with a friend to find the nearest town. There were no paths to follow in the middle of the swamp, so Cordero brought a roll of toilet paper with him to leave scraps on tree branches to mark his trail. In the wee hours, the two soldiers finally came upon a very small town with little more than a general store and a few other buildings.

Cordero was relieved to find that he could place a money order at the store, which, luckily, was open at 4 a.m. when he arrived. After sending his wife the cash and making a few purchases for himself, Cordero and his comrade made their way back to camp. However, they soon found themselves lost, unable to pick up the paper trail they’d left.

Lights alerted them to a road that gradually led them closer and closer to their camp. Negotiating the swamp on their way to the camp, the two had to cross a rope bridge that gave way as Cordero was crossing. The water below was infested with alligators, and one almost bit Cordero's leg off as he stepped on its head to make a leap to shore. Surviving their close encounter, the two made it into their camp just in time for the 6 a.m. roll call.

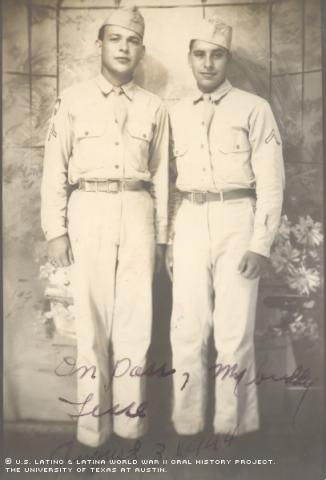

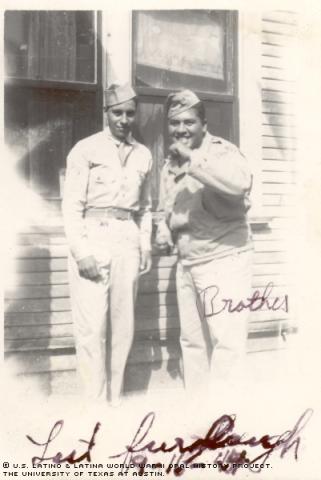

With the end of the Louisiana maneuvers, Cordero, now a corporal, was sent to Fort Sam Houston in San Antonio, Texas. Once there, he reunited with people from his hometown who’d been assigned to other regiments. He also made new friends and explored the city, but found some of the people were curiously opposed to his participation in the military.

"This Mexican lady, she told me, 'What are you doing in that uniform? You're Mexican; you're not supposed to be in an American uniform.' So I told her, ‘You know what? I was born and raised in this country,’" he recalled. "That's why I'm wearing this uniform."

Some Latinos in San Antonio had what Cordero called a "santanista" mind-set, a carry-over from the conflict between Santa Anna and Sam Houston.

"They hated to see a Chicano in an American uniform," Cordero said.

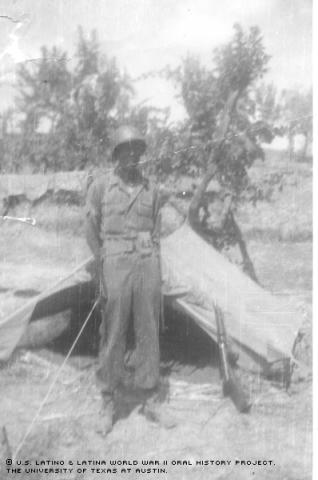

In early December of 1943, he headed for combat in Africa, where British troops were already fighting against the Germans. Cordero had great respect for the leader of the 8th British Army, General Bernard Montgomery, who later became a field marshal. The young corporal especially admired the field marshal's "set piece" battle plan -- a conservative but effective strategy that had succeeded in pushing the German forces off the African continent.

By the next winter, Cordero was stationed in the Italian village of Minturno. On a hilltop there was a Catholic monastery, which served as a makeshift operations base for German forces that were using a large artillery gun to fire at Allied forces. Requests to local government officials to return fire were denied, as it would have damaged the monastery. Eventually, Allied troops were able to take over the makeshift base, and moved on to liberate Rome.

In late 1944, on an Italian mountain, Cordero's squad came under fire from enemy troops. Cordero sustained serious wounds to his right leg and hip and had to be carried down the mountain by stretcher. At an Army field hospital, only a few miles from the front, the corporal underwent surgery to remove shrapnel from his hip and leg.

Cordero was granted a discharge from the Army because of his injuries, and by Christmas Day in 1944, he was bound for the United States. After docking in South Carolina three weeks later, he was sent to a hospital in Portland, Ore. Doctors tended to his injuries, operating on his leg again and removing his right kidney, which had been irreparably damaged by shrapnel.

Because of his extensive injuries, his homecoming would be delayed. Cordero recovered in the Portland hospital for about a year before he was able to join his wife and daughter in Los Angeles.

Ultimately reunited with his family, he settled in Los Angeles. Having survived encounters with enemy fire, dogs and alligators, he now leads a decidedly more peaceful life, indulging in daily three-mile walks and extensive plant collecting.

Mr. Cordero was interviewed in Los Angeles, California, on March 23, 2002, by Veronica Garcia.