By Voces Staff

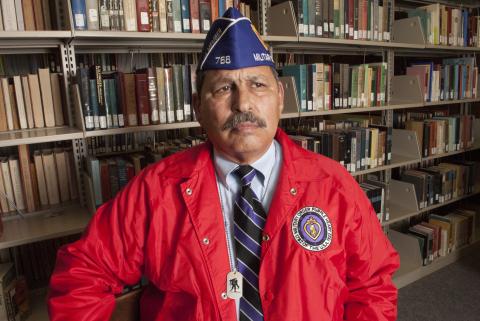

A bullet in his chest and scars on his stomach were lifelong reminders of Felipe Ramirez's Vietnam War experience.

"The first round of bullets hit the machine gun. Before I knew it, I was hit. I felt something. I took a big dive and went behind a tree and said to another soldier, 'I'm OK, I'm OK,'" he said.

The year was 1969. Ramirez, just 19, had enlisted in the U.S. Army after studying law enforcement for one year at Laredo Community College. A friend from high school had been killed in combat, and he thought volunteering to go to war was a way to get revenge.

"I wanted to go kill a couple of Vietnamese," Ramirez explained. "Back then, that was how I was thinking about war."

His family thought the decision was "crazy." His father, who had served 30 years in the Army, including in World War II, was scared for his son because he knew the risks.

Other Latinos, Ramirez said, were different: "They went to war if they were drafted. I volunteered myself," he said.

Felipe Ramirez III was born March 7, 1949, in Laredo, in South Texas. He was the third-oldest of 10 children born to Felipe Sanchez-Ramirez, a self-employed mechanic, and Hortencia Caballero-Ramirez, a homemaker.

He learned a strong work ethic from his father, who put in long hours to support his family.

To make extra money, the whole family went to California in the summers to work in the fields.

"We used to pick peaches, plums, a lot of grapes, tomatoes, potatoes. We were a big family. Everyone worked," he said.

When the family returned home, his father divided the money and gave some to each child to buy clothes, shoes and other necessities.

Growing up, Ramirez, his brothers and their friends often gathered to play baseball, hunt or go fishing at Lake Casa Blanca, a few miles north of town.

Ramirez liked school because there he could socialize and participate in sports such as football, basketball and swimming.

"But," he said with a laugh, "I was a troublemaker" who would hang out with friends and drink after school.

In 1968, U.S. soldiers killed several hundred unarmed civilians in the Vietnamese village of My Lai. Ramirez, who was about to graduate from high school, recalled his shock at the news and realized how tough it was to be in the war.

Once he started college, Ramirez felt compelled to volunteer. As soon as the paperwork was completed, he was sent to Fort Bliss, in El Paso, Texas, for basic training, and then to Fort Hood for advanced infantry training. He was assigned to Company C, 2nd Battalion, 7th Cavalry.

The training was tough, but Ramirez had an advantage. "I was young and in shape from football. A lot of them were not in shape," he said. "Training was still tough, but I had to do it."

Ramirez valued what he learned during training.

"The Army taught me how to survive -- how to shoot all kinds of weapons, how to kill hand to hand, how to read a map, pick food, be a doctor, how to communicate to get out of a situation," he said.

When he arrived in Vietnam, he said he became "a different person." From college student to artillery man, Ramirez experienced things he never could have imagined.

"It was hard, very hard, when we were in combat. In one raid, mostly everybody got killed; some got pulled to safety. From 400 dudes, 150 came out, and that was the worst," he said.

Base was at the hilltop LZ Professional in Chu Lai with 11 other men in the 1st Battalion, 46th Infantry Regiment. He described his base as "a beautiful jungle paradise. Except that you were in a war." His main duty was to be a machine gunner.

Living conditions were "normal," Ramirez said. "We slept in bunks. It was small quarters, but not so bad."

Days consisted of roaming the jungle, searching for enemies. Any free time was spent trying to get his mind off of what was going on around him. Ramirez and the other men would drink beer, listen to music or write letters home.

He did not recall any instances of discrimination during his time there and said he got along well with others. One man, in particular, became a good friend.

"I had a German friend; he was a medic," Ramirez said. "I would teach him Spanish, and he would teach me German." He lost contact with the friend after coming home from war.

Ramirez understood that the Vietnamese people were in a difficult situation, caught between the Viet Cong and government forces. "There were a lot of innocent people, a lot of in-between people. There were people just living in Vietnam, and these soldiers were coming in. It was hard for them.

"But if you gotta fight, you gotta fight," he said. "When we killed people, I used to go check out to see what people had," he said, sometimes finding gold teeth he could take from the bodies.

Ramirez carried a bullet in his upper chest, a wound he suffered in an ambush when his unit had been assigned to clear an area so an Army helicopter could land.

An officer told him to relieve the machine gunner, so he carried his gun and his pack to the location. He was trying to put the pack down when a Viet Cong soldier appeared and shot him with an AK-47. Ramirez's ammunition belt stopped one bullet, but other bullets struck him.

Ramirez served for two years; his injuries were too severe for a second tour. After he was wounded, he received treatment in Japan and later was sent home. He was discharged in August 1971.

Ramirez returned to his hometown and got married. He and his wife, Hortencia, had a son, Felipe IV.

He continued to have flashbacks of running through fields with deafening explosions in the distance. Fireworks on the Fourth of July were especially hard to bear. He was diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder and was still getting treatment and taking medication at the time of his Voces interview.

"You never forget war. To me, it was like yesterday. I never forget," he said.

He was awarded two Purple Hearts, two Bronze Stars, a National Defense Service Medal, the Vietnam Service Medal, and the Army Commendation Medal.

Mr. Ramirez died Dec. 20, 2016.

Mr. Ramirez was interviewed by Desiree T. Hernandez in Laredo, Texas. on Feb. 26, 2011.*