By Kristin Stanford

While still a teenager, Esteban R. "Steve" Garcia learned firsthand that destroyers -- unlike nerves or stomachs -- are made of nearly impervious steel.

As waves incessantly pounded the sides of the four-stacker destroyer he was on in the South Pacific -- a ship built six years before he’d been born -- he and other newly trained enlistees slumped over the sides, with crisp white uniforms and green faces. It was Dec. 18, 1941, and they were en route to Alaska on the USS Kennison.

Having grown up in the city of Mission, in the southernmost part of Texas along the border with Mexico, the 18-year-old wondered if he’d made a wise choice in volunteering for service. But the decision was part of a proud family tradition, with five of his brothers serving in the war effort.

One of his brothers, Marine Private Daniel Garcia, died in the first wave of troops going into Iwo Jima on March 2, 1945. Another brother, Private Agustí¬n R. Garci¬a, twice received the Purple Heart for injuries, the first time after being shot while parachuting into Normandy. Three other brothers served stateside during the war. Garcia notes further that four of his sons served in the Armed Forces during the Vietnam era and several grandsons served afterward in the military.

"I'd never been to sea or anyplace," he said. "Feeling the ship roll here and there, I'd rather die than be up there."

He’d already led a tough life, having toiled in the cotton fields of northern Texas. To help him cope overseas with a new set of hardships, he says he’d summon memories of his mother.

"The love of a mother is a true love. If you don't love your mom, you don't love anyone," Garci¬a said. "Even when I was overseas, my mother was with me [in spirit]. I imagine that's what kept me alive."

As a gunner's mate 2nd class on the USS Kilty, Garci¬a was involved in nearly 30 actions, and fought with tenacity in the Pacific Campaign and Okinawa landings. He was thrust into maturity swiftly, and his outlook forever changed.

"I didn't know what I was getting myself into," Garcia said, his vacant gaze fixed forward. "I don't like to talk about what I've seen, what I've been through [and] done."

One night, his ship dropped Marines off on an island in the area of Guadalcanal. It was an operation like many others the USS Kilty had been performing. By daybreak, it became apparent the Marines were outnumbered 20-to-1 and desperately needed rescuing. His ship responded but was bombarded upon arrival.

"There was nothing we could do," said Garci¬a, explaining that because their own men were dispersed on the island, the ship wasn’t able fire on their attackers for fear of friendly fire.

"I imagine [the Marines] were all killed," he said.

In April of 1945, the Kilty served as an escort to several ships transporting soldiers to the beaches of Okinawa. The ship made another voyage to Okinawa and on May 4, 1945, rescued soldiers of the USS Luce, which was sunk by a kamikaze. The ship returned to San Diego, Calif. in June.

Garci¬a's uniform would eventually display an Asiatic-Pacific Campaign Medal with two silver stars, a Philippine Liberation Ribbon with two bronze stars, Philippine Presidential Unit Citation, Honorable Service Lapel Button, American Campaign Medal, Amphibious Force Insignia and World War II Victory Medal.

The decorations were hard-fought, but despite having earned the accolades, he says he never felt he was treated as an equal among his Anglo counterparts. Regardless, he was a hard worker -- an ethic that can be traced to his childhood.

"You have to be taught to accomplish things or you won't," Garcia said. "[My siblings and I] grew strong because we accomplished what we chose to accomplish."

Before the Great Depression, Garcia performed custodial services at Our Lady of Guadalupe, the Catholic school he attended in Mission, Texas, in lieu of paying tuition. His family, 11 children and their parents, struggled to make ends meet and he did his part by shining shoes and selling newspapers after school.

"In our own way, we were doing alright. We earned our food, our living. We didn't have to ask anyone for anything," he said.

The Depression forced the Garcia family to pick cotton from dusk to dawn in fields north of their hometown. After completing the sixth grade, Garcia would drop out of school entirely. One hundred pounds of cotton was worth 20 cents at the time, and he was paid 25 cents per eight-hour-day of picking. The first of six brothers to enlist, Garci¬a says entering the service was a welcome invitation compared to the grueling days in the hot Texas sun.

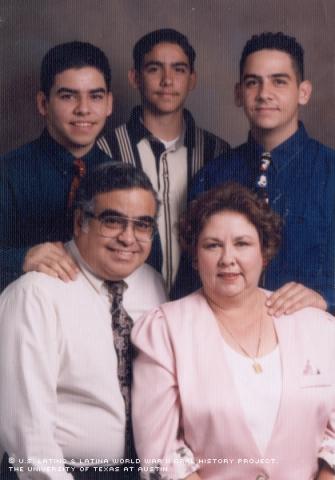

Many years have passed since the Garci¬a men were in the heat of battle. Except for the one brother killed in action in WWII, two of his brothers and three of his sisters have died from cancer or heart-related ailments. Three brothers and two sisters are still living. Garci¬a has been married four times. He had six children by his second wife: José Edward, José Edian, José Eli, Heriberto, Estéban Jr. and Elda. He had three stepchildren during his third marriage: Armando, Roberto and Alma; and two stepchildren from his fourth marriage: Sergio and Jorge.

Garcia was honorably discharged Oct. 25, 1945. He says he returned to his home in Mission, Texas, to find not much had changed in the way of segregation, widespread discrimination and prejudice.

A few birds singing, the rustling of grass and his own footsteps were all he could hear as he walked along a familiar dirt road in Mission upon his return. Suddenly, a swell of red dust swirled up on the horizon and the rumble of an old automobile grew stronger. Garcia recalls the truck stopping in the center of the road and blocking his path.

"You got papers to show me," a border patrol guard said roughly.

"I'm a veteran, an American citizen," Garcia recalled responding.

"In that case, you'll have no problem showing me your papers," he remembered the guard barking.

While undignified, the moment prompted Garcia to resume the education he’d been forced to interrupt prior to the war.

"When you're ignorant, you don't know how to defend yourself," he said, looking back at his encounter with the lawman.

He proceeded until the ninth grade, at which point he entered a trade school for cabinet making. He recently retired from his cabinet-making career, which included his managing his own shop.

The mental and emotional scars Garcia bears from the war are lightened by his veteran friends' support. Although he says that, at times, he feels alone, he has decided that, "Every day is a beautiful day, regardless of what kind of day it is."

Mr. Garcia was interviewed in McAllen, Texas, on April 6, 2002, by Liza Moreno.