By Rachel Vallejo

As the Enola Gay took off from the island of Tinian to drop the first atomic bomb over Hiroshima, Ernesto Hernando waited alongside his fellow servicemen to hear about the destruction.

According to the Navy’s online database of WWII casualties, the United States had been engaged in the two-front battle of World War II for more than four years, and had already lost hundreds of thousands of soldiers in the process. Hernando describes the mood of his unit, which was stationed on the island of Guam, about 100 miles north of Tinian.

“It was scary,” he said. “Now we see everything right away, but then there were no [real time] pictures.”

Hernando was born in 1923 in Cloudcroft, N.M., but was a resident of El Paso, Texas, when he entered the military. Although he was drafted into the Army in the fall of 1943, he chose to enlist in the Navy with two friends from his neighborhood, Frank Acosta and Tino Morales.

“We were from the barrio [neighborhood],” Hernando said. “But we got separated after training.”

Hernando was trained as both a lookout and a fighter-plane mechanic. His first post was on a troop ship headed for New Caledonia, an island just east of Australia. While aboard, Hernando served as a lookout.

“The ship had four sections and the lookouts would watch one-fourth each,” Hernando said. “We had to watch the water and the sky and report anything we saw to the bridge, even a can.”

After arriving in New Caledonia and unloading the Army troops the ship had been carrying, Hernando was assigned to an aircraft repair unit on an aircraft carrier. When asked what he was told to expect in the Southern Pacific, he says he had few ideas of what it would be like.

“We were anxious,” Hernando said. “There was something else in the air during the second world war. You wanted to participate, you wanted to, but I didn’t expect anything.”

Though Hernando didn’t start out as a mechanic before the war, he was no stranger to hard work. His experience in supporting his family at an early age translated easily into supporting his country when it called upon him.

Hernando attended Bowie High School in El Paso for three years and at 17 dropped out to join the Civilian Conservation Corps in order to financially support his family. While a member of the CCC, Hernando says he did various types of construction work, including building barbed-wire fences in New Mexico and constructing a holding facility for German U-boat captives.

“We got paid 30 dollars a month,” Hernando said. “I kept seven dollars and the other 23 would go to my mother to help the family. We were a big family. I had eight sisters and there were 11 of us [kids] all together.”

Even after serving in the war, Hernando and his family couldn’t rely solely on the government paychecks he’d received, so he began working at Farah, an El Paso-based manufacturer of men’s pants. While there, he transported pants to and from the sewing room. He says he didn’t enjoy the work there, so he quit and got a job at the Harry Mitchell Brewery

“I was one of the smartest ones when I got there,” Hernando said. “I could relieve any position. There was a German brewing master who took a liking to me and showed me the whole business.”

From fermentation to finishing, Hernando learned the entire brewing process. He enjoyed the challenges that the many charts and precise measuring offered.

“I missed it a lot when I went [to work at Safeway],” Hernando said. “It was kind of interesting and a little more important. I thought I was going to retire from the brewery, but then they shut it down.”

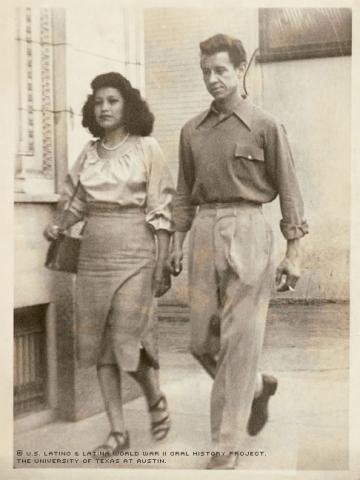

When Falstaff purchased the brewery in 1956 and subsequently closed due to increased competition in 1967, Hernando was forced to move on. It was then that he took his wife, Elisa Fernandez Hernando, and seven children to San Francisco to find work in another brewery, but ended up in the warehouse of Safeway, one of America’s largest grocery chains. After about a year and a half, Hernando and his family moved back to El Paso, where he continued to work at Safeway.

“I didn’t want my kids to grow up [in San Francisco],” he said. “I thought it was a little rough, but now it’s the same here in El Paso.”

Hernando drove a forklift by day and by night attended classes at El Paso Tech, the original building of which now houses Cordova Middle School. He studied bookkeeping and accounting at El Paso Tech in hopes that a little more education would help him in the job market.

“If you have a little more education, you do a lot better,” he said.

This is a philosophy Hernando has passed on to his children, which he says he hopes every young person understands.

“Our kids learned from us,” Hernando said. “We had a harder time, and I’m very proud of my kids. They’re better than I am because they’re more educated.”

When asked what advice he would give to America’s youth he said, “Go to school and get educated. There’s nothing like an education.”

Mr. Hernando was interviewed in El Paso, Texas, on September 1, 2007, by Maggie Rivas Rodriguez.