By the Voces Staff

Growing up in a northern Mexican mining town, Emilio Nicolás sat by his father's side listening to short-wave radio reports from the United States describing the advance of Allied troops across Europe during World War II.

Constantino Nicolás, who loved to read and listen to the radio, picked up some English from the broadcasts. Years later, he urged his son to learn English. Emilio would go to college in San Antonio, at first pursuing a career in pharmaceutical research. He would leave that field to become a pioneer of Spanish-language television in the United States, providing a crucial platform for Latino voices.

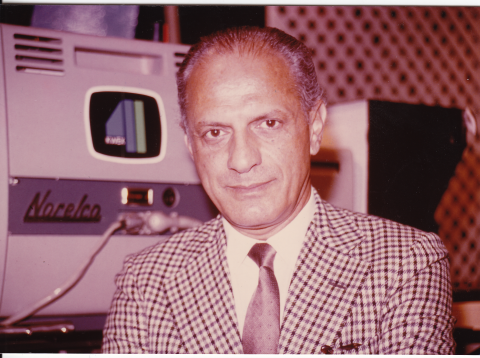

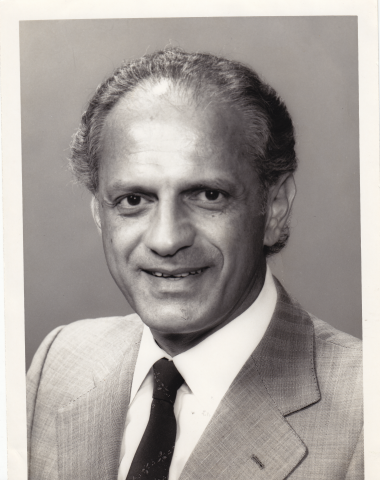

For nearly 50 years, Nicolás would be a force in the growth of Spanish-language television, starting out helping his father-in-law, Raoul Cortez, run KCOR-TV in San Antonio, the first Spanish-language television station in the continental U.S. The station would become the operations center of the Spanish International Network and part of what is now Univision.

In a 2005 address to the U.S. House of Representatives, Rep. Charlie Gonzalez, (D-San Antonio), remarked, “In this age of mass communication, some say if you can't see an event on television, it does not actually happen, so a pioneer like Mr. Emilio Nicolás Sr. was crucial for Latinos.”

Nicolás was born Oct. 27, 1930, in Frontera, a mining town in the Mexican state of Coahuila. His father and his mother, Miriam Saide Nicolás, had moved there from Bethlehem, in what was then Palestine, during the Great Depression. The town grew after American Smelting and Refining (later known as ASARCO) set up operations there.

The couple ran a dry goods store and raised their three daughters and two sons in the living quarters behind the store. The store was open seven days a week, from 8 a.m. to 8 p.m.

The Depression was far worse in Mexico than in the U.S. In America, people could at least stand in lines to get a bowl of soup. In Mexico, Nicolás said, “they didn’t have any lines. The government was broke. The whole country was broke. And it was just the goodness of people that helped them to survive.”

The family shared what they had. His sisters gave money to the unemployed people who gathered outside their store. Emilio said his older brother, Guillermo, gave people credit but never tried to collect.

After primary school, Nicolás' family sent him to an all-male boarding school run by the Catholic Marist Brothers in San Luis Potosi. He learned French, excelled in algebra and trigonometry, and studied international history.

“In those days, they were the strictest people you've ever met in your life, but they were very wonderful teachers,” Nicolás said of the Marists.

When Nicolás was 18, his father tried to enroll him at St. Mary's College in San Antonio. Despite the boy’s academic qualifications, the school did not accept him because he did not speak English. Administrators suggested he enroll in a U.S. high school to learn English, advice he followed.

Nicolás said he would make long lists of words from a dictionary, translate them into English and try to memorize them. He went to the movies every night, listening carefully to the dialogue and picking up English a little at a time. He recalls the moment when he realized that he finally understood what the actors were saying in the 1948 comedy “Sitting Pretty.’’

“I jumped for joy,” he recalled. “I'm telling you: The miracle does happen. At the end of the movie, I stayed and I saw it again, just to make sure that [my understanding] was for real. And it was.”

On his own, he went back to St. Mary's and was admitted on probation because he still didn’t pass an English competency test. But he was determined: By taking extra classes, Nicolás graduated within three years in 1951, earning a bachelor’s degree in biology.

The next year, he received a master's in biology from Trinity University in San Antonio in 1952 and then took a position with Southwest Foundation for Research and Education (now Texas Biomedical Research Institute) in San Antonio. Researcher Jonas Salk at the University of Pittsburgh had developed a polio vaccine, and there was a call for research labs across the nation to investigate ways to produce large batches of the serum.

As assistant to the foundation's chief, Dr. Nicholas Werthessen, Nicolás was one of three volunteers who agreed to work on the project, despite the dangers of working with the dry vaccine.

“If you inhaled, if you got anything from it, you were as good as dead,” Nicolás said. But he felt “a deep concern in knowing that this polio vaccine could save your kids and everybody else’s kids.”

Meanwhile, Nicolás had been dating Irma Alicia Cortez since his early days at St. Mary’s. He had been invited to an annual ball but had had to borrow a friend’s ROTC uniform because he didn’t have a tuxedo. Their meeting at the event was the start of a long courtship, and a new career for Nicolás.

Irma's father was Raoul Cortez, who in 1946 had launched the first Spanish-language radio station in the United States, KCOR-AM in San Antonio. Emilio and Irma dated for five years because her father resisted their marrying.

They finally won his blessing and married in 1953 at San Fernando Cathedral in San Antonio. Their first two children, Emilio Jr. and Miriam, were born a year apart. A third son, Guillermo, was born in 1963.

While Nicolás liked his work at the research foundation, the long hours were difficult for his family, and the pay was low -- $200 a month to start, later raised to $300. Meanwhile, his father-in-law was preparing to open a television station to join his radio station.

Channel 41, KCOR-TV, was to be the first Spanish-language television station in the continental U.S., as well as the first UHF (ultra high frequency) station, as opposed to the standard, very high frequency (VHF). The Federal Communications Commission had allocated nearly all the VHF frequency and was now handing out less expensive UHF licenses to meet the rising demand for more local stations.

Nicolás came on board, quickly showing an aptitude for the new medium. He wore several hats at the station. “I was fascinated with production,” he said. “I sat next to the production manager and before you knew it, I was producing programs myself.”

In the first year, the new station had only one RCA camera, so Nicolás devised methods for transitioning between scenes. He designed set backdrops that could be rolled out for programs and produced variety shows with performers from Mexico. He was making only a little more than he had at the foundation but received a second income producing commercials and jingles for national advertisers. “They paid me very well.”

He also became the news director, assigning reporters to beats and imposing professional discipline on what had been a disorganized operation.

“I said, 'This news department is going to have to be a news department. You cannot go and talk about anything you want within the news. You have to stick to the news.’ Some basic stuff,” Nicolás recalled.

By itself, Channel 41 was “doomed to failure,” he said. Most advertisers were not interested in a single-market station, especially one that broadcast in Spanish. Ratings agencies at the time didn’t measure Latino audiences.

Nicolás said UHF was “the real underdog frequency” then, because people had to pay $50 for a converter and antenna to receive the signal. He and a business partner, Rene Anselmo, lobbied Congress to require set-makers to build televisions ready to receive UHF signals. In 1961, Congress passed the All-Channel Receiver Act, authorizing the FCC to impose that requirement.

With loans, the station was able to stay afloat for six years. But New York banks weren't interested in offering further support.

In 1961, Nicolás joined Cortez’s former partner, Frank Fouce; Julian Kaufman; Anselmo; and Mexican media mogul Emilio Azcárraga Vidaurreta, to buy the station. The partners formed Spanish International Communications Corp. (SICC), a holding company for what would grow to several stations. Fouce died shortly afterward and was replaced by his son, Frank Jr.

They called their station KWEX, with their eyes set on acquiring a second station in Los Angeles, with the call letters KMEX.

“We wanted to somehow emulate what Mr. Azcárraga Vidaurreta had done in Mexico and Latin America,” Nicolás said. Azcárraga’s network, Telesistema Mexicano (later Televisa), was known as the “voice of Latin America.”

“We also knew that the Mexican-American population was anxious to have something like that.” And with the growth of other Hispanic populations, including Puerto Ricans, Cubans and Dominicans, “we thought the potential for growth was immense.” The partners added programming of interest to those groups.

Within a few years, there were seven stations, including in major cities such as New York, Miami, and San Francisco and Phoenix. The investors also opened a few low-power stations in cities such as Austin, Texas; and Tucson, Arizona.

“We didn’t make much in profits for the first seven years,” Nicolás said, “I always thought, in my heart and in my mind, that we’d be successful if we would just be patient.”

San Antonio was the center of operations, sending programming to the other stations, at first on tape. In 1976, KWEX launched the first television satellite uplink in the U.S., allowing rapid transmission of programs and ads to the other stations.

The San Antonio station had about two hours of local programming each day, including a half-hour newscast. But much of the programming came from Azcárraga’s company in Mexico.

In 1971, a new company, Spanish International Network, was created to handle advertising sales and distribution of programs to the SICC stations and to a growing number of affiliates.

But divisions were growing among the partners, including Azcárraga and others who wanted to change the name of SIN to Univision. Nicolás opposed the change because so much had been invested in building the SIN name.

He stepped down from SICC in 1987, when Hallmark bought the stations for $301.5 million, and SIN was renamed Univision.

Azcárraga's son, Emilio Azcárraga Milmo, moved the center of operations from San Antonio to Laguna Nigel, California.

“I was used to running my own show,” Nicolás said. “No program ever ran that we didn't either send by tape at one point or send by satellite” from KWEX.

Hallmark organized a dinner that year to honor Nicolás, with President Ronald Reagan, San Antonio businessman Red McCombs, and Texas Lt. Gov. William Hobby among the attendees.

After the sale, Nicolás formed Nicolás Communication and bought several low-power television licenses and made a deal with Mexico's Galavisión to carry its programming in the U.S. That deal later fell apart, and Nicolás agreed to affiliate the stations with the Home Shopping Network.

In 2004, he sold half of his stations to Pappas Television and half to Univision, according to his son, Guillermo. He sold the last of his Univision stock two years later.

He remains proud of what SIN accomplished.

By providing Latino communities information and news about culturally relevant events, Nicolás said SIN “wiped out” a sense of inferiority among Latinos. The company also hired and trained many Mexican-Americans to work in television.

For the audience, he said, “We showed them who they really are, where they come from, and they got used to the language and seeing other people like them” on television.

Emilio Nicolás was interviewed by Laura Barberena in San Antonio, Texas, on Sept. 26 and Oct. 4, 2011.