By Marisela Maddox

At a time when many Mexican Americans were segregated from Anglo Americans by socioeconomic and educational standards, Elfren Solomon confesses he rarely, if ever, witnessed ethnic discrimination in the military: The focus for Solomon and his comrades was fighting a war and overcoming the horrors of war.

"When you come to face the reality, we were fighting for our lives. We weren't bringing any nationality into factor," he said. "The main thing is we were fighting for survival. You had to depend on your buddy because he was watching your back. …

“[T]he individual race has nothing to do with heroism. You either got it, or you don't.”

Beginning in 1939, thousands of young American men enlisted in the military to serve their country and acquire military benefits.

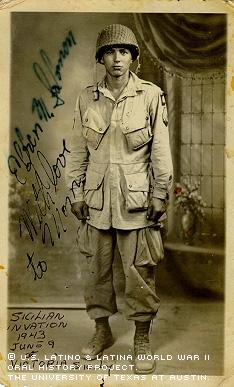

Solomon’s service in the military, first in the Army and later the Air Force, took him on tours of Italy and North Africa; he served as a drill instructor and an Airborne Artillery officer. During the airborne invasion of Sicily, Solomon's aircraft was among 27 planes shot down. He sustained back injuries after parachuting from the plane.

Born in Phoenix and raised in Yuma, Ariz., Solomon turned to the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) for the $30-a-month salary the government program provided. The "New Deal" program created by President Franklin Roosevelt's Administration to off set the affects of the Great Depression, allowed Solomon to contribute to his 15-member family. The family was particularly hard-pressed when his father, Charles Solomon, died in 1922 when Solomon was one year old.

Starting at age 9, Solomon did odd jobs such as shine shoes and sell newspapers to contribute to his family's income. As a teenager, he worked for Southern Pacific Railroads.

At 17, Solomon left high school two years shy of completion, entered CCC camp and eventually enlisted in the Army.

He recognized the benefits of joining the military, including an opportunity to learn skills and get an education.

A 13-year career with the U.S. Military followed. Far removed from the familiar environment of his Mexican American culture, Solomon matured during the war.

"The reality was you'd get killed or you'd become a POW. You were there ‘til the end of the war; we had no other time limit. The goal was to try and stay alive," he said.

Stationed in San Diego, Calif., Solomon admits to being surprised by the attack on the American military.

"We were not prepared for any war. We had antiquated equipment from WWI, rifles from WWI, and tractor-drawn guns form WWI,'' said Solomon, who added that he thinks the U.S.’ victory in WWII was lucky.

As the military deployed soldiers overseas to fight, men affirmed their commitment to their country, abandoning any resentment from past discriminations.

"I am a U.S. citizen. It was my business. I never thought of [prejudice]. I had too many good friends in the service to worry about it. I had no ill feelings," he said.

Solomon said he felt prejudice in the CCC camp, but once he was in the military, he didn’t feel discrimination.

Many recollections trouble him and other soldiers who watched the atrocities first hand.

"When you see a dead cadaver, a lot of things go through your mind, like, 'You'd hate to be laying there like that guy.' You can visualize yourself lying down like him," he said. "It's hard, damn hard. Once you smell a dead cadaver, you never forget it. The human body stinks worse than a dead dog."

The victory over Japan on August 1, 1945, marked the end of the war. A long journey home included stops in Italy, Berlin, France, Casablanca, South Africa, South America, Miami and Los Angeles. Solomon went home to his wife, Virginia Moreno, and child, born during his overseas service. He obtained his high school diploma from San Diego High School and went to college for two years. Adjusting to civilian life initially proved difficult.

"I learned to appreciate life a little more. I had more respect for my people," he said, adding, however that "the first six months were hard."

"There was no noise. It was too quiet. I was used to someone trying to kill me. You are always looking around to see if you are safe," Solomon said.

After the war, he worked for the Bureau of Reclamation, went to work for the railroad and finally ended up employed as an aircraft-engine mechanic and later as an inspector for the Navy.

Virginia, with whom Solomon had 5 children, passed away twenty years ago. He later remarried Olivia De la Rosa.

Mr. Solomon was interviewed in San Diego, California, on June 15, 2000, by Rene Zambrano.