By Destinee Hodge

In 1965, after two weeks at sea aboard the USS Gordon, Eddie Morin heard the captain declare over the loudspeaker for the first time that he and his fellow soldiers were headed to Vietnam. It was something they already knew.

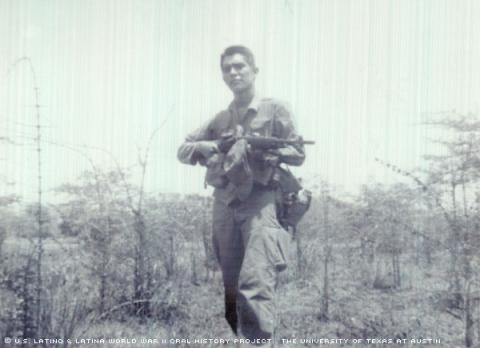

Morin was a part of the 18th Infantry Regiment, 1st Infantry Division, and he was among the first group of U.S. soldiers to set foot in Vietnam, and among the first to witness the horrors that came with it.

The Los Angeles native said it was one of the largest crossings ever. The men were not told where they were going when they boarded the ship at an Oakland harbor, but local news reports did not allow it to remain a secret.

“You had to be pretty dumb not to figure out what was happening,” he said.

Morin had always felt he had some larger-than-life shoes to fill. His father, Raul Morin, was a World War II veteran who later used his wartime experiences as a point of reference for activist activities.

“I always idolized my dad. I wanted to emulate him,” Morin said. He added later that his father helped to set up the first “local posts [in Los Angeles] for the American Legion and Veterans of Foreign Wars” and founded California’s first American GI Forum. Morin said his father wrote “Among the Valiant,” celebrating “Medal of Honor recipients of Mexican descent,” and protested against police brutality and unfair housing. Morin said that his father “felt strongly that the Mexican American veteran continued to face blatant discrimination in his own country.”

Morin was born in East Los Angeles, where he attended elementary school, junior high school and high school. He graduated in 1960.

Indifferent to the possibility of being drafted, Morin studied at a trade school for a year but quit in order to become a sign painter, the same job his father had before his wartime service.

“Up until the time I was sent to Vietnam I still didn’t think it had too much to do with me, “ he said. “It was worlds away, and it started out as a small story.”

Morin was drafted in June 1964, before the Gulf of Tonkin incident. Despite President Lyndon Johnson’s campaign as a peace candidate in that year’s presidential election, one of his first moves was to ramp up the military effort in Vietnam by sending in more troops. Morin was a part of one of the first battalion-sized groups to be sent to the Pacific.

After basic training in Fort Polk, La., and advanced training at Fort Riley, Kan., Morin found himself in Oakland, Calif., about to board a ship on its way to an unstated destination. A friend showed him a newspaper clipping that had the exact locations and maps of where the troops were going. Morin’s indifference to the prospect of going to war remained unchanged.

Upon arrival in Vietnam, Morin worked as a rifleman and guard, and he helped to clear land so that some of the first bases could be built in near Cam Ranh Bay. His unit also patrolled.

It was not until a few months later that he got his first taste of combat. Morin was transferred to an area near the Mekong Delta popularly known as the “Iron Triangle.” Historically, the Iron Triangle was a strong point for the Viet Minh, a Vietnamese force that fought against the French in Vietnam’s colonial war. The area became a strategic hiding place for the fighters in their new war against the Americans.

“We quickly noted the difference in our opponents,” Morin recalled later. “Our previous encounters were not … intense but here, the enemy soldiers were regulars with more discipline and skill. We started taking casualties, and the pace was more grueling.”

The labyrinthine system of tunnels and hiding spots proved to be a constant challenge to U.S. troops.

“They were tougher, they were smarter, they were wilier, they were craftier, they just knew more devious ways to hurt you,” Morin said.

Morin served in the Army for about a year and a half before he was critically injured by a Viet Cong ambush as he rode in a convoy. “It was a night move,” he wrote later, “and we were ambushed and then engaged in an intense firefight.” Morin considered himself lucky to have survived. “An explosion went off and wrecked the truck I was riding in. … It killed four fellows in my immediate vicinity, and I consider myself fortunate to have escaped death.”

He spent 13 months recovering in hospitals in the Philippines, Hawaii and in stateside medical facilities.

Morin was among the first group of soldiers to go to Vietnam, and so he was among the first soldiers to come home.

“I have no actual medals for valor,” Morin wrote later, “but I do have all the campaign ribbons and awards, and I am proud of the Combat Infantry Badge and Purple Heart that I wear on special occasions.”

For Morin, the difficult process of readjustment to civilian life was largely exacerbated by the strong anti-war sentiment in America.

“When I got back, I couldn’t blend back into society,” he said. “I didn’t feel normal, I was removed, I was out of it. I didn’t feel comfortable with the things I should have felt comfortable with.” He saw a bitter irony in his predicament: “[A]fter going through so much, I had more problems in adjusting to a society that was hostile to returning veterans.”

The prevalence of anti-war protests caused Morin and other veterans like him to internalize their anger over the situation because they felt that they could not change it.

“I don’t feel an overwhelming debt of gratitude to the war protestors -- in fact there’s a lot of resentment,” he said. “For you to act like you’re better than me, just because you didn’t feel like going, is wrong. … You’re not even noble; in fact, the closest you can come to emulating courage is to demonstrate against those who served.”

Morin wrote later that it “bothered me so much that I wouldn’t talk about my experience … nevertheless, I always felt that returning veterans were not accorded the respect that we deserved.”

After seeing a psychologist later in life, confronting his anger, enduring sleep problems due to Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder, seeing one marriage fail and a second one succeed, raising two daughters, and writing a book about his experiences, “Valor and Discord,” Morin has come to terms with his experiences, “with the rage and confusion that the Vietnam War brought on me.” He shares his opinion with anyone willing to listen.

“I’d like to tell people in general to remember that the G.I.’s job is to fight the war -- he doesn’t establish policy,” he said. “The best and worst of our society surfaced in thatugly episode,” he remembered later. “I pray that this nation never undergoes another divisive issue like that again.”

Mr. Morin was interviewed in East Los Angeles on June 9, 2010, by Henry Mendoza.