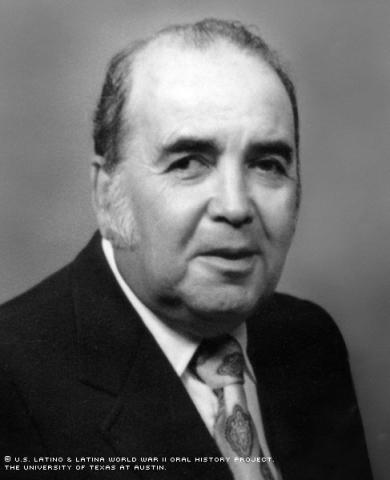

By Liliana Martinez

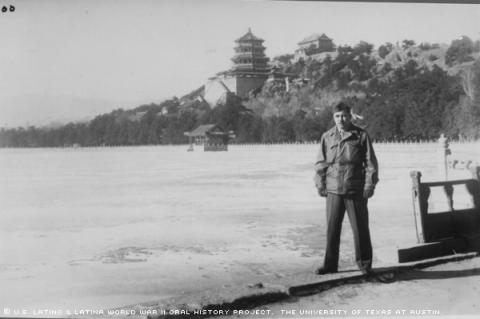

When Ed Idar was a teenager living in Buenos Aires, a neighborhood in Laredo, Texas, he never thought he’d volunteer as a civilian for Station X in England, and go to India and China while in the Army.

"I came to realize how big the world was, how many societies and cultures there are in this world," Idar said. "Seeing poverty makes you wonder, ‘Why can't we do things to help people?’"

And it was his thirst for helping others that pushed him to devote much of his life to working for the Mexican American community.

Idar would begin his involvement with the Civil Rights Movement when he came back from the war at the age of 25 and began studying journalism at the University of Texas at Austin in September of 1946. As a member of the Laredo Club, he wrote a resolution critical of Attorney General Price Daniel for an opinion that "opened the door" to school segregation of Mexican American students.

"I was not afraid," said Idar proudly. "I had been in the service and had dealt with generals, coroners and this and that and the other."

In 1950, he became a member of the American GI Forum and in 1951 became its state chairman, succeeding Dr. Hector Garcia. In 1960, after the GI Forum’s annual convention in Wichita, Kan., he and other fellow members decided to form the Viva Kennedy Club Organization and soon began printing bumper stickers with the "Viva Kennedy" slogan.

Getting Mexican Americans to the polls was a big challenge at the time. In order to vote, a poll tax of $1.75 had to be paid by every voter. The bumper stickers helped to stimulate the number of Mexican American voters.

The activity of Viva Kennedy Clubs nationwide was a large factor in electing John Kennedy president, particularly in Texas, which Kennedy won by only 30,000 votes. In some South Texas voting precincts where Mexican Americans predominated, Kennedy won up to 98 percent of the total vote.

"They were very influential in carrying out the election for Kennedy," Idar said. "A lot of people blamed the Viva Kennedy Clubs for that."

Idar says his biggest regret is not being able to vote when Harry Truman ran for re-election for president in 1948.

"I wanted to vote for the guy, but I was living in Austin at the time, going to the University … I was living way outside town. We had a tremendous snow fall January 30th and 31st, the last day to buy poll taxes," he said laughing. "There was no way I could've gone down town to buy my poll tax, so I couldn't vote."

Idar also noted it was almost impossible for Mexican Americans to come up with the money to pay the tax.

"For two people in a marriage, a husband and a wife, it was quite a bit of money,' he said. "It was a big hindrance, not [a] question about it."

Even though money was always a big obstacle, the GI Forum conducted yearly poll drives and increased the number of Mexican Americans who paid their poll tax. The GI Forum also encouraged its leaders and members to be politically active in their own community. These drives were initiated in 1949 and 1950, long before the Viva Kennedy Clubs were activated in 1960.

"We conducted poll-tax drives every year," Idar said.

In 1961, after the election was over, the Viva Kennedy Clubs became what was known as PASSO, the Political Association of Spanish-Speaking People Organizations, a dream come true for Idar.

"I always hoped that we could organize that type of political organization on a statewide basis to represent the Mexicanos," he said, "in soliciting support and getting things done by the state politicians."

According to Idar, up until then, Democratic Party politicians had always used Mexican Americans, but had never done anything to meet Mexican Americans’ needs. Most Mexican Americans were active as Democrats; so they rarely considered Republican candidates.

"Oh sure, they [Democrats] wanted our attention," he said. "They wanted us to vote on Election Day, but they never helped us with anything we wanted."

Even though PASSO promised to be effective, it fell apart at the height of its success in 1962, when it decided to endorse Price Daniel, who was running for reelections as governor and who had won two years earlier by a million votes. Idar and other Mexican American leaders in PASSO concluded that going for a liberal Democrat would again result in their being "used" by the Democratic Party.

"We thought it would be worth taking a chance," he said with a smile.

As he remembers, his own best friends turned on him and PASSO after this.

"They accused us of having sold out to Daniel because he offered us 100 jobs in the Texas Highway Patrol," he said.

Idar said a lot of kids would drop out of school during those years because school segregation was rampant and they were discouraged to remain in school and get a higher education. He remembers that in 1950, when he joined the GI Forum, Dr. Hector Garcia assigned him to work for the desegregation of the school system in Kyle, Texas.

"There used to be a wooden frame building on the left side (going south) of the highway," he said. "It was two, three rooms ... that was a Mexican school."

However, he said Mexican Americans in Laredo didn't face desegregation issues.

"In Laredo, no problem," he said laughing. "We had intermarriage. You couldn't avoid that."

Idar left Laredo in February of 1941 to work at Duncan Field as a clerk in San Antonio, Texas, and as far as he recalls, he never experienced any kind of discrimination at his workplace.

"There were few Mexicanos, but we didn't have any problems," he said.

He remembers his Anglo boss at Duncan Field watching the train taking the Station X Volunteers.

"I will never forget the old man ... crying," he said. "You could see the tears coming out his eyes 'cause he had lost some of his men."

Idar's ability to type and take shorthanded helped him get a position as a stenographer in the Army.

"I only had a high school education at that time, but I wasn't dumb," he said with a smile. "I could take shorthand about 200 words a minute and type at 75 words a minute."

He said he and fellow members of the Army didn't have any first-hand news, and that communication was censored, while they were overseas.

"You couldn't write home about a lot of things," he said.

When the war ended, he didn't have enough points to come back home, so he was transferred from Kunming to China Theatre Headquarters in Shanghai to once again work as a stenographer.

On June 6, 1946, Idar was discharged and returned to Laredo, where he spent the summer preparing himself to go to the University of Texas at Austin in September of that same year. He used the GI Bill to help pay for his education.

He received his journalism degree from UT three years later. While in Austin, he worked as the executive secretary for the American Council of Spanish-Speaking People, doing research about Mexican Americans.

He obtained a fellowship to finish law school three years later, and in 1956 he moved to McAllen to practice law.

While in the GI Forum, he also got involved in Hernandez v. Texas in 1954. The case involved Pete Hernandez, a migrant cotton picker, who was accused of murder in 1950. He was tried and convicted in Jackson County; however, the jury didn’t include any person of Mexican origin or with a Latino surname, despite the fact that the county was 14 percent Hispanic.

As GI Forum executive secretary, Idar would put together newsletters to try to raise money to cover court litigation expenses. But as he remembers, coming up with money was always a big problem, and as far as he remembered, the most the GI Forum ever got at one time when he was there was $10,000. But that didn’t stop Idar or his fellow active and committed friends.

"Our people were dedicated," he said. "They believed in what they were doing. They weren't expecting a salary."

When Nixon became president, Idar was working as an inspector for the Office of Economic Opportunity, evaluating poverty programs. But, as he says, things began to change once Nixon got into power.

"They turned us into an investigative agency, and I didn't appreciate that job," he said.

Idar's war years affected his personal life: Two weeks after he arrived in England, he met his first wife Joan Stringer, who became his biggest supporter.

"My wife went along," Idar said. "My wife was English. No tenia vela en el entierro when it came to La Raza. Yet she never stood in the way.""

The saying "No tenia vela en el entierro" literally translates to: “She had no candle at the funeral.” Within the context of Idar’s comment, the idiom implies Joan lacked a passion for the Mexican American Civil Rights Movement.

Joan died in 1985 after 42 years of marriage. The couple had two children: Rebecca Ann Brockway and Edward Stanley Idar III.

Idar remarried in 1994. His current wife is Maria Meza Rodriguez-Idar.

After the PASSO debacle in 1962, Idar moved to San Angelo, Texas, and became the only Mexican American to practice law in that area of the state.

He later returned to Austin to work full time for the Office of Economic Opportunity from 1968 to 1970, when he moved to San Antonio to work for the Mexican American Legal Defense and Education Fund (MALDEF). Idar worked for MALDEF from 1970 to 1974. While with the organization, he became head of the San Antonio office. He worked on several civil rights cases, including Regester v. Bullock, a case that brought about single-member legislative districts in Bexar County. In 1974, Idar took the position of Assistant Attorney General for the State of Texas, assisting in several police brutality cases before beginning the biggest case of his career, Ruiz v. Estelle. Idar argued this landmark prison rights case on the side of the Texas Department of Corrections, but the issue wasn’t resolved until years after he retired from the Attorney General's office in 1983.

After his retirement and the death of his first wife, Idar returned to San Antonio in 1993.

Even though things weren't easy during his years of advocacy, Idar knows he and his friends made a big difference in the state of Texas.

"We laid the groundwork ... and I was just being myself," said Idar with a smile. "If there's a thing to be said, I'll say it."

Mr. Idar was interviewed in San Antonio, Texas, on December 2, 2000, by Maggie Rivas Rodriguez.