By Tony Cantú

Charles Vizcaino Uranga, a self-made millionaire who fought at Normandy during World War II, left little doubt about who his hero was, during his interview in 2001.

Relating anecdotes from his childhood in Alpine, Texas, he summoned vivid memories of his father, Clemente J. Uranga, who, according to Uranga, helped Latinos gain admission into the town's high school. The older Uranga was very adamant about Latinos doing for themselves, his son said.

Memories of his father's hard-working nature are vivid to Uranga, and he attributed his own desire to succeed in business to him. But in addition to a strong work ethic, the elder Uranga also inculcated a philosophy to his sons about the harsh realities of working for mainstream employers during an era of hardship. In those days, Latinos had difficulties borrowing money from banks.

"He told me, 'If you get $10 an hour or if you get $50' -- in those days $50 was the maximum that a Hispanic made - 'Whatever you make, you got to make more for the gringo,' because that's the expression that they used in those days.

"He said, 'If you can do it for him, you can do it for yourself,'" Uranga recalled recently. "And I've never forgotten that."

Memories of his mother, Guillerma Vizcaino, are hazier, given her death at 33 of a heart attack as Uranga neared his 8th birthday. But he notes that it was she who taught his father -- who had no formal schooling -- how to read.

"My mother would teach my dad how to read and write and (do) arithmetic at night, and over a period of two months, he learned how to read and write," said Uranga of his father, who ran a small grocery store in Alpine. "As time went on -- by himself -- he learned how to read English. He couldn't write it, but he could read it.

"He was a very smart man." … "If he had had an education, I don't know what he would have been."

One of nine children, Uranga dropped out of high school in the 11th grade, not out of economic necessity, but because he felt ready to take on the real world. He moved to El Paso and then decided to marry his girlfriend, who was attending Sul Ross College. They married in Del Rio.

"And then Uncle Sam decided to take me on a tour of Europe," he said with a laugh. At that time, he’d been working in Fort Sam Houston in San Antonio, where he and his wife lived.

He was inducted into the service on Nov. 27, 1942, at the age of 20. From Del Rio, he was transported to El Paso, Texas, for basic training at Camp Hulen in Palcacios, Texas, before going to Louisiana for maneuvers.

In Louisiana, the term "basic training" took on a literal meaning, as he recalled how sticks were used to simulate gunplay and small sacks of wheat flour were thrown from overhead aircraft to represent bombing raids.

Eventually, he became a corporal for the 459 A.W.B, an automatic weapons unit that saw tours in Normandy, Northern France, Ardennes, Central Europe and Germany.

But even while in the throes of maneuvers, he had no notion as to where he would be sent for combat, he recalled.

"We didn't know where we were going," he said. "They sent us on a train and we went up to New York, and in New York, we found out we were going to go to England."

Arriving in England as part of a fleet of 75 ships filled with American soldiers, the scene was a far cry from the sticks and flour sacks scenarios of Louisiana.

"We landed in Bristol, England, and when we landed in England, they were bombarding the city as we were being unloaded from the ships," he said, able now to laugh about the abrupt change of scenery. He quickly learned he’d be part of the Normandy Invasion.

For any veteran, memories of combat abound. For Uranga, one of his most vivid involves an attempt to gain a strategic stronghold during the Normandy battle. With the Germans advancing toward the same goal, two P-51 airplanes were supposed to arrive to clear the way of oncoming enemy tanks to aid his infantry. The aircraft never appeared.

Still, the mission couldn’t be abandoned. Breaking out of Normandy to a nearby city was crucial because roads were still intact there, which would enable the American forces to expand. He and a lieutenant executed their orders to fight back the enemy troops, which involved putting their own lives in peril by scoping the landscape to determine the location of the attacking Germans.

"He and I went up to the front. And I'll never forget when we thought we had located the machine guns. There was an opening of about 30 or 40 feet and we had to run through there to be able to see down to see where the machine guns were," he said. "And of course we knew they were going to shoot at us."

Uranga recalled how the sweat on his brow and the trembling of his hands belied his determination to gain the stronghold.

"I was shaking. My hands were going this way and so were his," said Uranga, reenacting the involuntary spasms prompted by fear. "And we were perspiring and he (the lieutenant) says, 'Are you scared?' and I said, 'Yes I am.' He said, 'I'm scared just like you are. But don't ever let your subordinates know that you're scared because they look at the leaders. And you and I are the leaders.'"

Running in succession across a clearing, the two managed to elude machine gunfire. But they still had to go back to secure their reinforcements in order to fire back at the enemy with the full throttle of their weaponry.

"Later, we went through a little village and he said, 'There's going to be some snipers, so be careful,'" Uranga said. It was in this village where the lieutenant decided to change the formation and maneuver around Uranga to the front of the caravan.

"So we shot at the windows and kept going, but there was a German tank waiting for us on the other side and the hedgerows were high, so he was hiding very well," Uranga said. "I was in the leading ... half-track ... and he (the lieutenant) motioned for me to hold it -- I don't know why -- but then he went ahead of me. About five or 10 minutes later, we made a curve and all we heard was BANG! The German tank fired at the half-track and blew it up. Only he and another kid escaped. The rest of them were killed. All five."

It was only until the following day, when more infantry arrived, that the mission was completed successfully. Uranga's valiant efforts later earned him a Bronze Star with a "V," which stands for valor.

Uranga was near the banks of the Elbe River near Berlin when he received word that the war was over. He was discharged on Oct. 21, 1945.

Returning to Texas after the war, Uranga set out on his goal to be a successful businessman. Initially, he ran a namesake grocery store in Alpine, Texas -- Charlie's Food Market -- before purchasing the Eagle Oil Co. in Eagle Pass, Texas.

As a broker in the energy business, Uranga would purchase refined products from providers throughout Texas in the energy industry -- gasoline, diesel, propane and butane -- and export them to Latin America. The launching of the business initially was jeopardized when it became questionable whether he would be able to get a $10,000 bank loan. To this day, Uranga says he’s convinced the bank attorney's objections to the loan were less an assessment of business risk and more because of his being a Mexican American. Finally, he got the loan.

"He didn't give any reason, he just made it look like they couldn't make me a loan," he said. "And the reason was that I was Hispanic."

Uranga was able to launch his business by virtue of that $10,000 loan. Originally, the business operated with only "one beat-up truck" and a single trailer, he recalled. Twenty years later, "I had something like 40 trailers, I had over 550 railroad cars going to Mexico every month, and another 150 steady going into Central America," competing head-to-head with such industry giants as Shell Oil and Gulf, as well as with large independent concerns.

He sold the business to Oklahoma-based MidAmerican Pipeline in 1977 and settled in San Antonio, where he dabbled in the real estate business, buying, remodeling and selling shopping centers under the corporate banner of C.V. Uranga Enterprises. In the heyday of his business interests in the 1980s, the prominent Uranga Towers on San Antonio's North Side attested to Uranga's business success.

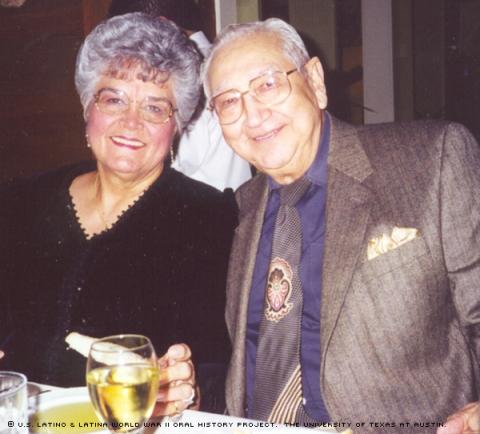

Today, Uranga is more familiar with the environs of another tower, living in the penthouse of a luxury highrise apartment building in North San Antonio with his second wife, Yolanda Mendoza Uranga.

Asked to what he attributes his post-war success, Uranga comes full circle in the discussion about his life, summoning once more memories of his own personal hero.

"Determination," he said without hesitation, before quickly adding: "And the upbringing that daddy gave me."

Mr. Uranga was interviewed in San Antonio, Texas, on January 27, 2001, by Tony Cantú.