By Ashley Clary

The laugh-worn eyes of Arthur B. Smith hide a courageous yet triumphant story. Not only did he face the dangers of the 1942 Bataan Death March and three years in a Japanese prisoner of war camp, he went on to lead a productive and fulfilling life.

Smith was born June 14, 1919, to José Padilla Smith and Isabel Britton Smith in Santa Fe, N.M. Neither of his parents received more than a third-grade education. One of eight brothers and sisters who grew up in Santa Fe, Smith graduated from high school and joined the military in 1940.

As a member of the New Mexico National Guard’s 200th Coast Artillery Regiment (Anti-aircraft), Smith and his fellow guardsmen were sent to military base Clark Field in the Philippines in November of 1941 to train Filipinos. It was a doomed assignment.

The Japanese simultaneously surprised attacked U.S. troops at Pearl Harbor and Clark Field on Dec. 7 of that year. The only weaponry Smith’s division and the inexperienced Filipinos had was guns, as well as warplanes, of which the Japanese destroyed more than 100. By contrast, only seven of the Japanese’s planes were downed, the first of which Smith's battery shot with a 50-caliber machine gun, but soon the planes began circling higher, out of gunfire’s reach.

The Japanese eventually forced the American and Filipino forces back to prepared positions in Bataan, a peninsula in Manila Bay. On Apr. 9, 1941, the Americans surrendered.

"We didn't want to," said Smith in a television interview on March 13, 2001. "In fact, we had already put everything in the trenches to wait for the [Japanese]. But they said 'no'. We had to surrender. There was no way we would have survived."

The captured Americans and Filipinos were forced to march 60 miles from Bataan to Cabantuan. The trek became known as the Bataan Death March because about 10,000 lives were lost, the majority being Filipino troops. An estimated 100 to 300 Filipinos died each day during the march, and about one to five Americans were lost per day.

During the ordeal, a Japanese soldier ripped off Smith's rosary and dog tags. He later made himself a new dog tag with a piece of his mess kit, so his body could be identified if he didn’t survive.

After a short stay in Cabantuan, he was forced on one of the infamous "hell ships," ending up in a labor camp in Hanawa. Like many others, he went to extensive lengths to survive.

For example, Smith kept a small stone with him when he went on work detail; when he perspired, he rubbed the sweat off with it.

Later at night, he would put the salt on the stone in his rice portion for extra nutrition. Also, he and fellow prisoners stole as often as they could, sharing all of their loot.

"That's how we would help each other out," he said.

Smith resorted to eating dogs, cats, rats and worms in order to survive. During his three years at the camp, he contracted dysentery, malaria and cholera on several occasions. He went seven days without water; twelve days without food. His weight dropped from 164 to 72 pounds.

Under these terrible conditions, Smith and the other prisoners sabotaged what they could. They loosened caps on drums of oil or gas so the contents would seep out. They bent the fins of bombs so they would stray off course.

It wasn't until after the August 19, 1945, atomic bomb on Hiroshima that they finally got rescued. Smith spent several months at a hospital before he was discharged that same year at the rank of Staff Sergeant.

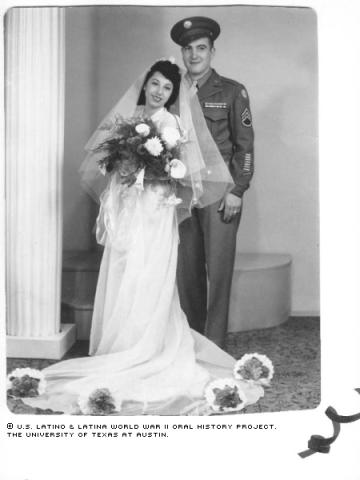

Upon his return To New Mexico, he married his high school sweetheart, Bessie Pacheco. But before he could do that, he had to overcome another major hurdle: Bessie couldn’t find the perfect wedding dress.

Fortunately, he’d taken back to the U.S. a white parachute that had dropped food and medicine to him and his comrades after the Japanese left the camp and before U.S. troops arrived to liberate them. They used that parachute for her wedding dress.

Smith began working as a manager at Sears & Roebuck Inc. He held that position for 28 years, until he retired in 1980.

He also began the hobby of carving out of wood Native American kachina dolls, each one representing a different god or spirit. Smith eventually created a respected collection of more than 1,200, with one of his dolls even selling for $21,000.

Mr. Smith was interviewed on March 13, 2001, in Santa Fe, New Mexico, by Karleen Boggio-Montgomery.