By Martin do Nascimento

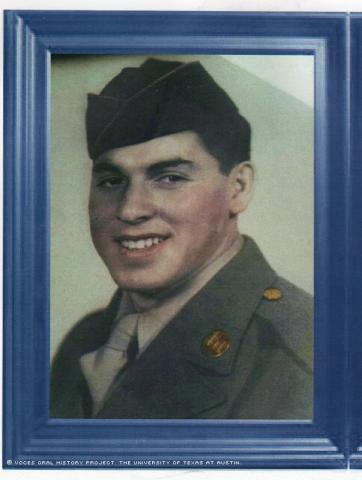

Antonio Becerra has always found a way to remain steadfast, persistent and determined in the face of adversity - first as a Mexican American growing up in rural Texas in the 1920s and '30s, then as a German prisoner of war and finally as a six-time political candidate - unsuccessful the first five times.

In his late 80s at the time of his interview, "Tony" Becerra was still living in his hometown of Rosenberg, 34 miles southwest of Houston.

Becerra's parents, Jose and Severa Galvan Becerra, were from Guanajuato in central Mexico and, like so many of their countrymen, made the 900-mile trek to Rosenberg in search of a better life. Better, at least, in some regards.

"I remember my dad telling us - that was during the Depression - my dad used to tell us to be careful not to come across the tracks at night after 10 o'clock because the Ku Klux Klan would beat you up," recalled Becerra of his childhood in rural eastern Texas. Back then, Rosenberg's neighborhoods were split by the railroad track running from Houston to San Antonio.

"In most areas around here, there's poor people on one side [of the tracks] and the ones that have a little money on the other side," Becerra said. In the summers Becerra and his friends would sneak across the tracks in the evenings to swim in the cooling tanks of the town blacksmith; the town's public swimming pool was for whites only. They had to sneak back to their side of town before it got too dark and trouble came out.

Not that the daytime didn't hold its share of horrors as well. At school, teachers prohibited Becerra and his friends from speaking Spanish. If they were caught speaking Spanish, punishments ranged from being forced to walk laps around the fields until they were exhausted to being rapped on the knuckles with a wooden ruler.

The white students were hardly any better.

"I remember that one of the [white] kids had some boxing gloves, and he was always fighting somebody. He asked me, 'Come on, I'll take you on.' I was probably in the second grade and he was in the fifth grade, but he was bullying me so I said, 'Yeah, I'll take you on,'" Becerra said. "That was the first beating that I got."

He said his parents never complained or got involved in school-related matters. He believes they were reluctant to advocate for their children because they had lived with discrimination in the United States for so long and had learned the price of boldness the hard way. All over the country, Hispanics suffered routine discrimination that extended from day-to-day slights to egregious miscarriages of justice.

"For the adults, you couldn't find a restaurant because they wouldn't let you go and eat. If you were traveling, you couldn't get a hotel or motel because they wouldn't rent you a room," Becerra said.

What's more, especially in the South in the 1930s and 1940s, Hispanic Americans were often denied their right to vote, as were African Americans.

Then, in 1941, World War II broke out.

"I was still in high school. I must have been 16 because I remember that I wanted to volunteer, and I wasn't old enough," Becerra said. "I felt patriotism. I felt like I had to go because I was living here in the United States, and I felt like I owed something."

Eventually, Becerra turned 18 and was drafted. He was sent to San Antonio for evaluation and from there traveled to Oregon for training. Becerra had never before left Texas but from Oregon he was sent to California, to Boston, to Liverpool, and finally, to Le Havre in France.

Assigned to the 103rd Regiment of Combat Engineers and later to the 28th Infantry Division, Becerra fought in some of the fiercest battles in the European theater. He took part in the Battle of Huertgen Forest, on the Belgian-German border, where he was recommended for a Bronze Star by a corporal in his company.

He would be unable to receive the award, however, because he was captured while participating in the Battle of the Bulge in the Ardennes; he managed to escape into Czechoslovakia only days before the war's end.

Surprisingly, though, one of Becerra's most prominent recollections of the war was the relative lack of discrimination that he encountered.

"The higher-ups preferred English, but they wouldn't get after you if you spoke Spanish," he said. Even the Nazis, Becerra said, who were driven by a dogma of racial supremacy, never treated him any differently from the other American prisoners for his Hispanic heritage.

"You could breathe up there," Becerra said. "Over here, it's hard. I met people [during the war] that lived around this area and we were buddy-buddies over there. But when we got back over here, I run into them once in a while and they act like they don't know you."

That made coming back to Rosenberg difficult, but it also set the scene for Becerra to run for local political office six times until he was elected in 1992.

"I was walking home from downtown and I looked back, and I looked to where all of our old houses were and I thought to myself, 'I can't leave, I got to try to help,'" he said. "So since then I've been pulling for the people."

Becerra, the father of 14, said he could have moved away and had greater opportunities; he could have gone to college in Houston under the GI Bill. But he chose to stay and "try to see if I could help the people by what I knew."

And he has dedicated his life to promoting minority rights in Rosenberg, both publicly and as a private citizen.

Becerra joined the GI Forum in Fort Bend County and served in a variety of positions, including local and district chairman. During those stints, he expanded the organization's mission to fight against discrimination.

He became a businessman, owning and operating several startups: Tony's Lounge, Modern Barbershop, Palladium Ballroom, and later Tony Becerra Insurance Co. He organized softball teams, hosted Easter egg hunts, and threw dances and parties for the minority community in Rosenberg - all with the goal of promoting empowerment through voting.

"My thing was to get people together and it would jump over to voting, so that's how I used to get them," Becerra said.

Even after the Voting Rights Act was passed in 1965 and after its extension to non-English-speaking Americans and expansion to Texas in 1975, Becerra saw that few Mexican Americans in Rosenberg were voting.

"Hispanics are hard," he said. "If they don't feel it's going to benefit them, they don't get involved. But what the blacks did [the civil rights movement] opened the doors better for the Hispanics because you don't see the Hispanics doing sit-ins and doing stuff like the blacks used to do. They [Hispanics] didn't feel it was going to help, but they found out different."

Changing the attitude of the Hispanic community toward voting was also why Becerra ran for public office in Rosenberg five times before being elected the on his sixth attempt in 1992.

"I think we were outside of City Hall waiting for the numbers and someone told me, 'Hey, you won.' And I said, 'No, I didn't win.' 'Yeah you won!'" Becerra recalled of the election night.

Becerra's niece, Lupe Uresti, was elected the town's first Hispanic mayor the same year.

"I'm sure there are [some things that haven't changed] because discrimination is still here; it's kind of put under the table. ... I did what I could," Becerra said. "I think it's changing because I see more people getting out to vote. Before, the younger generation didn't vote and [now] I see more younger people getting involved."

Mr. Becerra was interviewed by Martin do Nascimento in Richmond, Texas, on March 23, 2014.