By Haldun Morgan

"We were in Saipan when I had my first taste of combat. Not combat, [but] of bombs being dropped on us, trying to sink us. And I'm staring at the airplanes dropping, and I'm sure everyone is gonna hit us."

Before his initiation into World War II, Alvino Mendoza wondered what it would be like.

"For an 18-year-old, you begin wondering, after seeing so many movies, what it's really about, or whether you had the fortitude to do what you see others doing, or what you know others had done," Mendoza said. "I suppose it was a curiosity, part of feeling how much, how much machismo was in me. Whether I was man enough to face the enemy, or whatever you want to call that, combat and what I would do. I was scared, but at the same time, I was eager to find out what it was about. I was able to see combat on my way. After the first night, I had all the [combat] I needed. I wanted to be back home."

It was an offhand comment by his girlfriend that led Mendoza to join the Navy in 1944, rather than follow the path of most young men into the Army. The Army was the most dangerous branch of the military during the World War II conflict.

He recalled the recruiting officer asking him, "Where do you want to serve?"

"What do you mean 'Where do I want to serve?'" he recalled asking.

“You want to go to the Navy, Army, Marines, Coast Guard, Air Force?”

“I don't care where I go, it's not my choice. You are the one that's drafting me. Send me wherever you want to go.”

“Well, no. I'm gonna give you the choice,” went the conversation.

"And that's when I remembered her, when she asked me to choose the Navy. So I said, 'I'll take the Navy,' [and] that's how I ended up in the Navy."

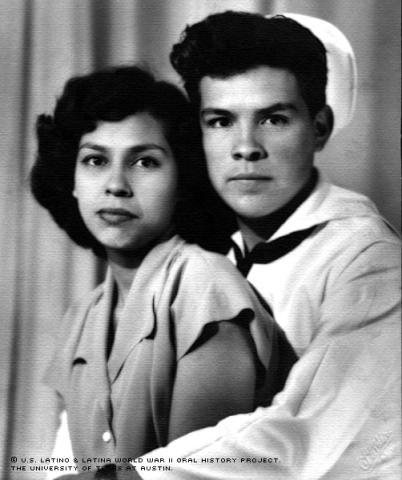

The woman Mendoza referred to eventually became his wife, Rebecca Vasquez Mendoza. Days prior to the above exchange with the military inductor, Vasquez had suggested to Mendoza that he join the Navy.

"I was the only one, of everybody who was inducted that day, who didn't hear anybody being asked where they wanted to go," he said, meaning that nobody else was being asked where they wanted to be stationed. "I just hear the stamping, ‘Army.’"

As luck or fate would have it, Mendoza obliged Rebecca that day in 1944. In that conversation, which may have saved the life of Mendoza, the couple's lifelong commitment to each other began.

Born in Round Rock in 1926, Mendoza moved with his family to Austin in 1928. His mother was a Texas native. His father, who came from Mexico during the Mexican Revolution, fled the disasters of that war. Ironically, 18 years later, their son would fight for their adopted country in a different war.

Mendoza was born at a crucial time in the history of the United States. In the late ’20s and ’30s, America suffered its worst economic disaster, the Great Depression. In Texas, most of the labor Mexicans did was in the fields. Living conditions were poor for these migrant workers.

Mendoza lived in the fields as a child.

"Sometimes we would build a fire, next to a tree, and sleep on our bags of cotton we had filled the day before. No shack, just under a tree," he said.

In the ’30s, Mendoza's father "worked just about anything. Did a little bootlegging to support the family," he recalled.

Mendoza attended school until 1941; the year America entered World War II.

"It was during that year, 1941, that my dad [went to stay in Houston and] began to work in the ship yards around Houston. And my older brother was also [drafted]. He was just turning 18," Mendoza said. "So I was left as the eldest in the family, my mom and my younger brothers and my younger sister. And for some reason, I just didn't feel like I needed anymore education. I was wasting time."

Left to take up the role as man of the family, Mendoza dropped out of Austin High School during his freshman year. School hadn't appealed to him much.

"[I] had very little interest in what was happening, mainly because I lived in an impoverished neighborhood where the biggest concerns were where is your next meal coming from," he said.

Three years later, Mendoza's draft number was called by Uncle Sam.

"I knew by the time I was 17, I knew it would be another year [and] I'd be called, because my older brother had already been called," Mendoza said. "Most of the boys that were a little older than I had been called up, and they were leaving."

After choosing the Navy, Mendoza was trained to be a member of the amphibious forces at Camp Wallace in Galveston, Texas, "landing on the beaches." In October of 1944, Mendoza was about to experience WWII as a seaman for the Navy.

One thing that concerned him about the Navy was the lack of training others had received.

"That's one of the odd things about what I learned in World War II," he said. "How can they assign people to positions with absolutely no training?"

For example, Mendoza recalled an instance in which a shipmate didn't fire in the midst of a kamikaze attack.

"Can you see him?" he recalled asking his shipmate.

"And he said, 'Yeah, I can see him,'” Mendoza recalled his shipmate responding.

“Well, damn it, fire!” Mendoza replied.

But his shipmate did nothing.

“The ship that was right next to us opened up on him, so as he was coming to hit us, they open up. And he turned and went right after the other ship, and he hit them. The other one [plane] came around and we had the best shot at him. At both planes we had the best shot at, but we didn't fire any. The other one turned around and hit another ship."

Mendoza learned after the other ships had been hit, that his shipmate had never before been assigned to that gun, and he didn't know how to use a pedal, which was the firing device.

Another instance that puzzled Mendoza occurred during an attack in which a "Condition Red" was called. A Condition Red was when they were ordered to shoot at anything in the sky, meaning that no friendly planes were flying alone. Sometimes Americans would shoot down their own planes.

"I remember we were under condition red. We were looking across the water at an aircraft carrier that was there. And all of a sudden, I saw this plane being launched by one of our carriers. My thought was, 'Why are they launching the plane when we were under condition red? Somebody is gonna shoot at it…’

"And I saw a plane veer off to the side, west, and I saw him pull over a mountain. One of our cannons shot it out. One big ball of fire, blew it out of the sky," Mendoza said.

Another plane launched from the same carrier met the same fate.

"That made you have a hole in the pit of your stomach," he said. "But it was carelessness."

In late March of 1945, Mendoza was involved in the battle of Okinawa, the largest amphibious operation mounted against Japan by the Americans in the Pacific War. Fighting in Okinawa lasted until June 21, 1945, but it officially ended on July 2. The losses were numerous for both sides. Okinawa was the staging point that allowed America to successfully bomb Japan, which led to the eventual dropping of the Atomic Bomb on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. In the Okinawa campaign, more than 100,000 Japanese people had been killed. America lost 12,000 troops, with more than 36,000 wounded. Mendoza took part in the mayhem.

"We went in there on March 28th," he recalled. "We went into a cove, and immediately, when we arrived, we were constantly under attack, mostly by the kamikaze planes. And I could look at the stern of a ship and see destroyer escorts that were on patrol duty, in the cove, get hit and split right in half."

This worried Mendoza, because the ship he was on, the U.S.S. St. George, wasn't a destroyer; it was an auxiliary sea plane with a squadron of patrol seaplanes that held ammunition, bombs and fuel.

Japan sent the world's largest ship, the Yamoto, to the battle of Okinawa on April 6, 1945. Weighing in at 72,000 tons, and packing nine guns with huge 18.1-inch diameter barrels, the Japanese sent the Yamoto to Okinawa with only enough fuel for a one-way trip. The suicide mission ended on April 7th, as America repeatedly torpedoed and bombed the ship.

Mendoza had his ship put out of commission during the campaign in Okinawa.

"We got hit by a suicide plane, and it was early in the morning. Your reaction is like quick thinking," he said.

After the ship's guns failed to sink the incoming bogey, the military word for enemy plane, Mendoza braced for the worst by grabbing on to a hatch and hoping to hit the water.

"I was afraid I would land on one of the decks below, which was solid steel. And so I am looking, and I'm grabbing. It took a matter of seconds [in] your mind," he said, snapping his fingers to indicate the speed at which he was thinking.

"Your thoughts and everything, [it's just] like when they say that you see your lifetime in a few seconds …"

When the plane hit the ship, it struck the thickest part, the steel crane that lifted the seaplanes onto the ship, which was eight feet in diameter. The plane also penetrated the deck into the sleeping quarters, killing pilots that had just come off of patrol.

Mendoza and his damaged ship were then sent to Guam for repairs. It was while they where in Guam that he and his fellow sailors received the news of Japan's surrender. World War II was over.

The Navy sent Mendoza to Japan with other occupation forces heading to Nagasaki. While there, he came into contact with a Japanese family who insisted he was Japanese. His almond-shaped eyes, or his fair skin complexion, may have been the reason for this mix-up.

"I felt that maybe my features had some to do with [it]," he said. "Then I began to get concerned -- they may think I'm a Japanese traitor. And I'm walking there in the streets; I may get shot at from one of these houses here.

“And it got to where I didn't want to go by myself in the street. And I tried to explain that I descended from Mexican parents. I didn't know how to do it. I would say a bunch of things, and try to draw little maps about the United States, Mexico. Yeah, I'm Mexican, my father's from Mexico."

Race came into play several times during Mendoza's military career.

"I took my neighborhood character into the Navy. I had a lot of fistfights in the Navy over racial remarks, but I took that from the neighborhood. I was very touchy ... I don't know what the word for it is, sensitive to it. But I began to meet people that I realized had no bias, at least my opinion was," Mendoza said. "Sometimes they mistook [me] for being Italian. Some ask me if I was French. Even the captain asked me [what I was]. I don't know why."

The question 'What are you?' revealed a lack of knowledge about what or who was a Mexican American.

"I met people who actually told me that they didn't know what a Mexican was," he said.

Growing up in East Austin during the 1930's, Mendoza had little interaction with Anglos.

"Before I left, [I] was strictly associated with Mexicanos, ever since I grew up. That's where I learned my Mexican history, from my grandparents, from the neighborhood elders. The language I spoke at home was strictly Spanish. I never spoke in English. My father never spoke a word of English to me, and neither did my mom," Mendoza said.

During the war, however, he made some Anglo friends.

"Some of them went out of their way to treat me as an equal. In fact, some of them looked for my friendship," he said.

But being around Anglos did a little more for Mendoza.

In the ’40s, Mexicans and Mexican Americans were still labeled as inferior in the Southwest. They were restricted from some public places, including restaurants, swimming pools, theaters and bathrooms. Many jobs, including city jobs, weren’t accessible to Mexicans, Mendoza recalled.

"We didn't have a Latino, or Hispanic, policeman here in Austin until [the] early 1950s. He shot an Anglo robber on 6th Street,” Mendoza said. The thief “robbed a drug store, so [the policeman] ran and shot him in the leg. He was fired immediately. …

"We didn't have a Mexicano bus driver at all. You couldn't find a Mexicano driver in one of the trucks, picking up the trash. You found them (Mexicanos) picking up the trash or digging the ditches, but you didn't find Mexicanos as foremen or as craftsman in the city, or the county, or anything like that,'' he recalled. … “I don't think there was a policy, but it was an understood policy. Wasn't a written policy."

After fighting in a war with Anglos as partners, Mendoza returned to Austin in 1946, and took a different approach to the way he looked at the world.

"I did come back with a little more self confidence. Because I had mingled with nothing but Anglo troops, and I couldn't see how they could be better than me. I knew I could do anything just as good as anybody else," Mendoza said.

With this new sense of empowerment, he became politically involved in the East Austin Community in the early ’50s. His activism is rooted in Christianity, he said.

"I learned that early in life that it's not what you do for yourself, it's what you do for others, that will eventually be what we might be judged as," He said.

At one point, Mendoza even thought of running for political office; however, he listened to his wife Rebecca, who told him he would have to be a good liar to be a politician. Since she said she didn't want to be with a liar, he declined to run.

Today, the Mendozas live in the house that they built.

"We dug the foundation, and she helped me. I was a carpenter by then. She helped me raise the walls; she helped me get on top of the roof," he recalled. "She's expecting another kid and we're both on top of the roof trying to put the rafters there. Most of it we've done together. She has been the strong arm."

They raised seven children, five boys and two girls. All of their sons are either involved in the Navy or Air Force, their eldest daughter is married to an Air Force man and they have a granddaughter in the Army.

Mr. Mendoza was interviewed in Austin, Texas, on October 20, 1999, by Haldun Morgan.