By Ali Vise

Catching a midnight train in Fresno, Calif., Alonzo R. Rivera Jr., watched his mother, draped with a blanket, crying as she said goodbye. At that moment, the work of his childhood harvesting grapes and cotton became a thing of the past. He recalled his fathers departing word: Im going to see if youre a real man now.

As the son of migrant workers, Junior as his parents referred to him, spent summers in the agricultural fields. He is the oldest of three siblings, all of whom were farm workers.

I was ashamed to say I worked in the fields, he recalled. That was the bread and butter to help out my parents.

Rivera spent his school years at Kirk Elementary, Edison High School and San Joaquin Catholic High School -- unmotivated. He didnt participate in clubs or extracurricular activities. He regretted that later, wishing he would have applied himself. He commended the faculty and education he received, as well as classmate Annie Brannen, who let him cheat off her tests in subjects like history, math and English.

He recalled that in the fifth grade at Kirk Elementary he wrote letters to a fellow students father who was a prisoner of war. Later on, his older male cousins Ynes, Robert and Ronnie Hidalgo -- enlisted in the Korean War. These two war connections led to his decision to enlist in the military.

Rivera had become involved with local gang called The Sinbads, drinking and getting into gang fights. In 1955, he went to live with his maternal grandmother, Lira, because I was not a good son to my parents. It was his grandmother who knew that a better future awaited him.

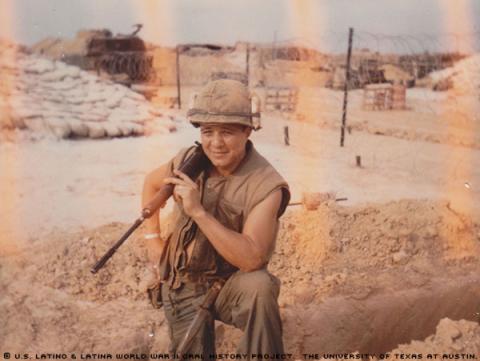

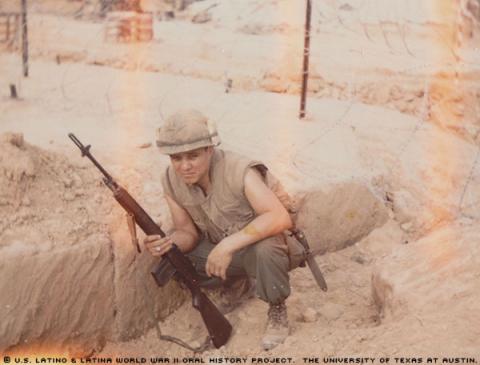

On Sept. 19, 1961, at the age of 21, he enlisted in the U.S. Marine Corps.

I thought I was King God, he said with an amused smile. But would I get a rude awakening at the Marine Corps Depot in San Diego . I went into a culture shock and that was the best thing that happened to me.

Many of his Latino friends had enlisted at the same time he had, including Rich Medina and Alfred Flores. While training in San Diego, Rivera was grouped with several men he knew from Fresno.

The majority of us from Fresno, Latinos and Anglos were joining the war, he said. You didnt see any prejudice, everyone is treated the same. They took any attitude away the first time you were there.

His community became aware of the vast number of Latinos fighting overseas when the names of the wounded appeared in the local newspaper.

The same year he enlisted, Rivera married Carmen Lozano, a girl he had taken to prom. Her inspiration and strength motivated him to become a Marine. In his free time, he wrote letters to her as often as possible. He really missed her cooking. But about once a month, she sent care packages filled with Mexican delicacies such as tamales, peanuts, pumpkin seeds, as well as tapes so he could record messages.

After leaving Travis Air Force Base near Fairfield, Calif., Rivera felt he received adequate training when he went to Vietnam on February 17, 1968. However, he knew nothing about the Vietnamese culture. His sole knowledge was to refer to the Vietnamese as Charlie.

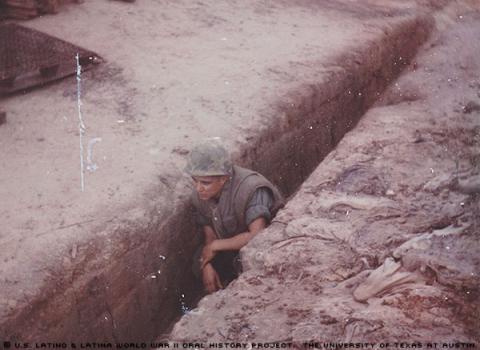

We went in there as a do or die when we fought the NVA [North Vietnamese Army], we werent fighting the Viet Cong, he said. They did traps, like jungle sticks, but the NVA were well trained, well equipped. The NVA had the hours of our breakfast, lunch and dinner down at Camp Carroll.

As a member the Kilo Battery 4th Battalion 12th Marines, a day in Vietnam consisted of maintenance and gun preparation followed by night firing missions. Rivera proceeded to transfer to the 3rd, 2nd, and 1st Marine Divisions during his service.

I can relate more to the evening, we would be firing to the unit that was in harms way, he said. The sleep shift would start at 6 [p.m] to midnight and midnight on.

Rivera was discharged in Jan. 18, 1981, but he continued his government service for 23 years with the U.S Customs and Border Protection. Decades after being discharged from the Maries, the war remains with him: he suffered from prostate cancer due to Agent Orange, he said, and Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder.

His wife passed away in 1972 of leukemia. He remarried in 1994 for three years before divorcing.

Ive had bad marriages, where it [PTSD] affected me as a husband, as a father, it has affected me with the illnesses I carry. Its something I have to accept, he said. I cannot go into a Vietnamese restaurant or socialize with any Vietnamese. I wish I could change that because the South Vietnamese people were not at fault for that.

He said he believed the war could have ended sooner, had the White House not insisted on sending more men to Vietnam. In return for his service and leadership, he earned two Navy Commendation Medals and two Purple Hearts.

If I had to do if over again, knowing I would be going through this, I would do it in a micro-second because Im a proud American

(Mr. Rivera was interviewed on June 7, 2010 in National City, Calif., by Olivia Puentes-Reynolds.)