By Jacob Martella

Coming back from the Korean War, Adolfo Alvarez knew he had to do something with his life.

He had survived nine months along the 38th Parallel holding the line against the North Koreans, not knowing if he would return to his family in the United States. Now, he wanted to make a difference for the Hispanics in South Texas.

"I said to myself if I make it back, I'm not going to raise hell, but I'm going to do something constructive so that this would not be in vain," Alvarez said.

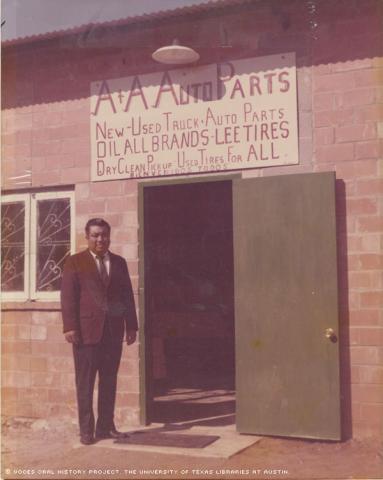

But it took a while for Alvarez to be in a situation where he could help his fellow citizens. In 1973, he opened A&A Auto Parts in Pearsall, Texas, giving him the financial independence needed to be a leader in the Mexican-American civil rights movement.

By the time Alvarez retired from public service in 1994, he had served as a county commissioner in Frio County and had been the first Hispanic to run for the state Democratic executive committee.

Alvarez's journey to political activism began in Harlingen, Texas, about 25 miles northwest of Brownsville. He was born to Genaro Alvarez and Dominga Ybarra on May 27, 1931, two years after the couple had come across from Mexico. The elder Alvarez had been politically active in Mexico but wasn't able to do the same in the States.

"They didn't have [the opportunity] to engage in anything except to provide for us, the family, which was working every chance they got," Alvarez said. "They didn't have a chance to do anything else."

The conditions in Harlingen for Alvarez's family were "horrendous." There were dirt floors and no electricity, no running water, no bathrooms.

"That's enough to drive a man crazy," Alvarez said.

Adding to the family's struggle was the fact that no one knew much about how the government worked. Even when Alvarez got to high school he only "had a vague idea" about what the government was.

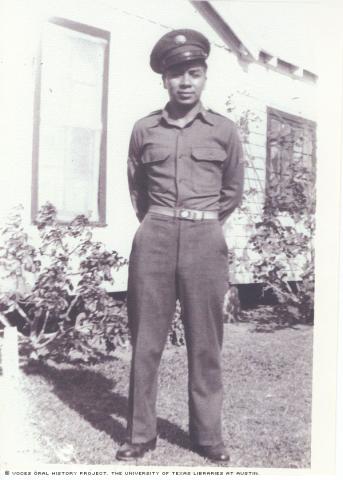

But that changed in a way in 1950. Shortly after graduating from high school, Alvarez "got a letter from Uncle Sam" drafting him into service during the Korean War. He first traveled to San Antonio to sign up, then was sent to Fort Jackson, S.C., for boot camp. From there, he was transferred to a base in Indianapolis and then Fort Hood, Texas, before finally heading to Korea in February 1951.

Korea was just about work and war for Alvarez: There was no sight-seeing or exploration. He and his fellow soldiers were brought into the country during the middle of the night and, before they knew it, they were at the 38th Parallel, the dividing line between North and South Korea.

But Korea afforded Alvarez an educational opportunity: He began learning more about the inequality between Anglos and Hispanics back home in the States. He started talking with other soldiers, finding out what they had and trying to understand how he could have what they had.

Finally, he confronted the big question: Why was he fighting in the war while things were still unequal back at home?

"You're going to war for what?" he said. "For nothing?"

That's when he made the decision to become more active politically if he made it through the war and returned home.

But Alvarez's venture into politics and helping the Mexican-American civil rights movement took a bit of back seat when he returned in 1953. He took a job as a labor contractor for farmers, living in various cities throughout South Texas. In 1956, he married Guadalupe Morales in Harlingen. The couple would go on to have nine children, four girls and five boys.

Finally in 1963, Alvarez and his family settled down in Pearsall, 50 miles south of San Antonio. A few years later, he started becoming more politically active when the Raza Unida Party came to the Pearsall area.

The Raza Unida had started in Crystal City in 1970, offering a more activist alternative to the Democratic Party, which had traditionally been the party supported by Mexican Americans. The hope was that the Raza Unida candidates would be Mexican Americans dedicated to improving the lives of their people. Two of its principals were Jose Angel Gutierrez and Mario Compean.

Alvarez immediately understood and supported the Raza Unida because it was an important leverage for the Mexican American people.

Still, the Raza Unida represented radicalism for many: some thought it was getting people shot, "which they were not. They didn't have anyone convicted for murder."

The party boosted the political power of Mexican Americans in Texas. Alvarez said that because of the Raza Unida, Mexican Americans had opportunities for improvement.

"We just got tired of that (lack of power) and wanted to do something," Alvarez said.

But Alvarez's involvement came with a price. In 1972, the president of CW Marvin Produce Co., a San Antonio, Texas-based firm to which he delivered produce, told Alvarez there had been complaints about him getting involved in politics. The farmers Alvarez collected the produce from weren't happy with it.

"You either did what the Anglo said or you were out," Alvarez said. He wasn't afraid of that; he had expected as much. And he had a plan: opening an auto parts business.

"I had enough knowledge of the auto parts business to make a go of it," he said.

A year later he opened A&A Auto Parts, setting himself on the road to financial independence, which he knew was necessary to be more active in the civil rights movement.

"When you have a profitable business, it gives you a sense of independence," Alvarez said.

His friends warned him about starting an auto parts business. He knew Anglos wouldn't buy from him so he counted on Hispanic customers. To bring them in, he started selling barbecue on Saturdays and running lotteries.

"You would sell so many tickets; you would keep some of the profits," he said. "It's illegal but it was under the table."

Finally, his auto parts business became established and was consuming so much of his time that he stopped selling barbecue to concentrate on auto parts.

As his business grew, so did his activism and his leadership in the community. Alvarez was named commander of the local Veterans of Foreign Wars post in 1975 and led the charge to get the post a new building that would be available for the community to use in dances and other functions. The accomplishment won over many in the local Hispanic community.

"People looked up to me for some reason or another," Alvarez said. "I chose to dig deeper and take things faster and better."

His efforts continued when Andy Hernandez asked him to help the Southwest Voter Registration Education Project, started by Willie Velasquez in 1974 to educate Mexican Americans about their right to vote. The project was similar to techniques used in the South to get African Americans out to vote. It was an intriguing idea.

"They told us it was strictly no violence," Alvarez said, referring to the project.

His political activity drew some hostility in a town accustomed to Mexican Americans being docile.

One day at his auto parts store, an Anglo man called out to Alvarez saying, "I want to kill you." Knowing what would happen if he did step outside, Alvarez remained inside and called the sheriff.

"I told the sheriff, 'I'm not going to go outside, but if he comes inside of my store I'm going to kill him,'" Alvarez recalled. "He said, 'Don't do that.'"

Within minutes the police came and ran the guy off, but the threats continued. Another time, a group of Anglos came to his house, threatening him and his family. As he had before, he didn't go outside and instead called the sheriff, who resolved the problem without issue.

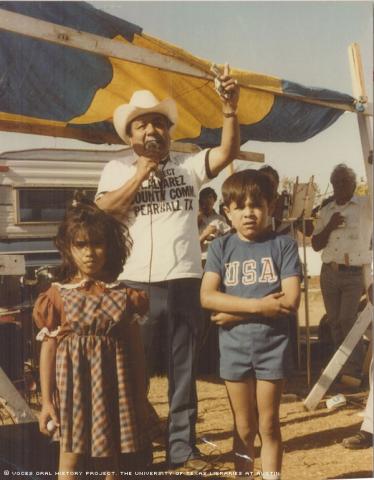

Still, Alvarez continued his mission. In 1980, he finally ran for a spot on the Frio County Commissioner's court and won by 23 votes. He served until 1984. He continued in politics, running for and winning a spot on the state Democratic Executive Committee in Fort Worth, Texas.

Alvarez said he accomplished everything he wanted to during his 16 years as a public servant.

"I was able to see that the Hispanic people had the opportunity to participate in the political system," Alvarez said.

At the time of this interview in 2015, Alvarez is 83 and living in Pearsall. Some of his children have moved away but remain close. And while he is no longer active in politics, his family has continued what he started. One son, Alberto, was elected mayor of Pearsall in 2014. Another son, Rick, was appointed city manager of the town the same year.

Alvarez said he never had to push his family into politics. "They could see what I was doing and understanding what I was trying to do," he said.

Looking back on his life and where things have come since his time growing up in Harlingen, Alvarez said he's proud of everything he and his family have done because "we tried to do it the right way." He also hopes future generations will continue to be politically active.

"That's where things are made, and that's where things are changed," Alvarez said.

Mr. Alvarez was interviewed by Maggie Rivas-Rodriguez on Feb. 28, 2015, and by Jacob Martella on March 29, 2015, in Pearsall, Texas.